What’s considered a “normal” glucose level?

Your doctor will likely test your blood glucose levels as a screening test for diabetes during a standard yearly check-up. Additionally, many people track their glucose at home with an over-the-counter finger-prick test. When you check blood glucose (also called blood sugar), either at a doctor’s office or with a home finger stick glucose monitor, the results are in milligrams (mg) of glucose per deciliter (dL) of blood. (Note that in many countries, the standard measurement is mmol/L; to convert the values below to mmol/L, divide the mg/dL by 18.)

One of the most common glucose measurements is fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or fasting blood glucose (FBG), and it’s found by checking blood glucose levels after not having any calories at least eight hours before the test. According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), people can be classified into three categories depending on their fasting plasma glucose levels: normal, prediabetes, and diabetes. To be considered “normal,” fasting glucose must be under 100 mg/dL.

Post-meal glucose levels are also meaningful, and high post-meal glucose levels can worsen glucose control over time and lead to obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, impaired exercise and cognitive performance, and other health conditions. While it is not unexpected for glucose levels to increase after a meal as the glucose from the meal is released into the blood, if this level is too high, it is not good for health and can predispose one to disease over time. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) guidelines for managing post-meal glucose levels, nondiabetic people should have a glucose level of no higher than 140 mg/dL after meals, and glucose should return to pre-meal levels within 2-3 hours. Post-meal hyperglycemia (elevated glucose) is defined as a glucose level >140 mg/dL 1-2 hours after ingesting food or drinks.

These blood sugar test methods mentioned so far rely on a single point-in-time measurement to determine if your levels are normal. Recent advances in continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) technology allow you to track your glucose levels over 24 hours and gain insight into deeper trends associated with overall health and wellness, such as glycemic variability, a measure of the up-and-down swings in glucose throughout the day. However, there are no standardized, universally accepted criteria for what “normal” 24-hour glucose values are using CGM technology. Scientists continue to gather information about glucose levels in healthy people using CGM technology.

Of note, CGM devices measure interstitial glucose levels (glucose from the fluid in between cells) compared to blood/plasma glucose levels (glucose in the blood) measured in the FPG tests. While interstitial glucose and blood/plasma glucose levels correlate highly, they are not precisely the same, and diagnoses are not made from interstitial measurements.

Below is a summary overview of data about 24-hour glucose trends in nondiabetic people wearing CGM to understand better “what’s normal.”

Want to learn more about your glucose levels?

Want to learn more about your glucose levels?

Levels, the health tech company behind this blog, can help you improve your metabolic health by showing how food and lifestyle impact your blood sugar. Get access to the most advanced continuous glucose monitors (CGM), along with an app that offers personalized guidance so you can build healthy, sustainable habits. Click here to learn more about Levels.

CGM Studies In People Without Diabetes

One study from 2009 entitled “Reference Values for Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Chinese Subjects” looked at the glucose levels of 434 healthy (people without diabetes or obesity) adults using CGM and found the following:

- On average, their daily glucose levels stayed between 70–140 mg/dL for 93% of the day, with very small portions of the day spent above 140 mg/dL or below 70 mg/dL.

- Also, their mean 24-hour glucose levels were around 104 mg/dL (± 10 mg/dL)

- 1-hour post-meal glucose values average 121-123 mg/dL for breakfast, lunch, and dinner

- 3-hour post-meal glucose values were around 97-114 mg/dL.

- Peak post-meal values appeared to be around 60 minutes after eating.

- Mean fasting glucose was 86 ± 7 mg/dL.

- Mean daytime glucose was 106 ± 11 mg/dL.

- Mean nighttime glucose was 99 ± 11 mg/dL.

A 2010 study, “Variation of Interstitial Glucose Measurements Assessed by Continuous Glucose Monitors in Healthy, Nondiabetic Individuals,” looked at a healthy population of 74 people that included children, adolescents, and adults during daily living using CGM. This research showed that:

- Glucose levels stayed between 71-120 mg/dL for 91% of the day.

- Levels were lower than 70 mg/dL for 1.7% of the time and greater than 140 mg/dL, only 0.4% of the time.

- Mean 24-hour glucose was 98 ± 10 mg/dL.

- Mean fasting glucose of 86 ± 8 mg/dL.

Compared to the first study mentioned, these healthy, nondiabetic people appeared to have a tighter glucose range, spending the vast majority of the 24-hour period between 71-120 mg/dL.

A third study, from 2008, entitled “Characterizing Glucose Exposure for Individuals with Normal Glucose Tolerance Using Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Ambulatory Glucose Profile Analysis,” looked at 32 people with normal glucose tolerance wearing CGM for approximately 29 days and showed the following findings:

- Amongst all participants, 24-hour glucose average ranged from 94 mg/dL to 117 mg/dL

- Overall mean glucose level was 102 +/- 7 mg/dL

- Mean daytime glucose was 105 ± 8 mg/dL

- Mean nighttime glucose was 97 ± 6 mg/dL

- Participants spent 93% of time between glucose values of 70-140 mg/dL, with 3% of the time below 70 mg/dL on average and 4% of the time above 140 mg/dL on average

- Looking at people in the study, some spent as little as .3% of the time (4 minutes per 24 hours) at values > 140 mg/dL

- Some healthy people in the study spent approximately 2.8 hours per 24 hours at glucose values <70 mg/dL, and an hour < 60 mg/dL

Learn more:

A fourth study, “Continuous Glucose Monitoring Profiles in Healthy Nondiabetic Participants: A Multicenter Prospective Study,” from 2019, examined 153 healthy, nondiabetic children and adults ages 7-80 with normal mean BMI of 24 ± 3.2 kg/m2 wearing CGM for up to 10 days. This study showed:

- Mean glucose levels of 99 ± 7 mg/dL

- Standard deviation of glucose levels of 17 ± 3 mg/dL

- Zero glucose readings >180 mg/dL

- 89% of glucose sensor values fell between 70-120 mg/dL

- 96% of glucose sensor values fell between 70-140 mg/dL

- 2.1% of glucose sensor values were >140 mg/dL

- 1.3% of glucose sensor values were <70 mg/dL

A 2007 study, “Continuous Glucose Profiles in Healthy Subjects under Everyday Life Conditions and after Different Meals,” looked at 21 healthy young people using CGM. These participants were between ages 18-35, had a healthy BMI of 22.6 ± 1.7 kg/m2, and were examined eating standardized meals as well as regular meals of their choosing. Mean fasting glucose for these participants was 80 mg/dL. This study found:

Under everyday life conditions:

- Mean 24-hour glucose concentration was 89.3 ± 6.2 mg/dL (range 79.2-101.3 mg/dL)

- Mean daytime glucose was 93 ± 7.0 mg/dL

- Mean nighttime glucose was 81.8 ± 6.3 mg/dL

- Participants spent ~80% of the time between glucose values 59-100 mg/dL and only 20% of the time between 100-140 mg/dL

- Glucose was above 140 mg/dL for only 0.8% of the day

- Mean pre-meal glucose levels were 79.4 ± 8.0 to 82.1 ± 7.9 mg/dL

- Mean time to post-meal glucose peak was between 46 and 50 minutes

- Mean peak post-meal glucose levels of 132 ± 16.7 mg/dL at breakfast, 118 ± 13.4 mg/dL at lunch, and 123 ± 16.9 at dinner

Under standardized meal conditions with a moderately low percentage carbohydrate (50 grams, 26.8%), high fiber (12.8g), high-fat meal (47 grams, 56.7% fat), and high protein (30.9 grams, 16.5%), participants displayed:

- Mean peak post-meal glucose levels of 99.2 ± 10.5 mg/dL

- Mean post-meal change from baseline of 20.2 ± 7.2 mg/dL

- Mean time to peak was 57.5 ± 24.5 minutes

Finally, the 2018 paper, “Continuous glucose monitoring is more sensitive than HbA1c and fasting glucose in detecting dysglycaemia in a Spanish population without diabetes,” assessed 254 people with normal glycemic function wearing CGM for 2-5 days. The mean BMI of these participants was overweight, at 27.3 ± 4.7 kg/m2. Their results found:

- Mean fasting glucose of 84.6 ± 7.2 mg/dL

- Mean 24-hour glucose was 104.4 mg/dL

- Mean daytime glucose was 106.2 mg/dL

- Mean nighttime glucose was 102.6 mg/dL

- Participants spent 97% of the time between 70-140 mg/dL

- Participants spent 1.6% of the time above 140 mg/dL

- 9.7% of participants had post-meal (breakfast and lunch) glucose levels that reached >140 mg/dL

- 12.1% of participants had post-meal (dinner) glucose levels that reached >140 mg/dL

Learn more:

What does the Levels glucose study show?

Levels is running an independent review board (IRB)-approved study that looks to use the aggregate anonymized glucose data from our members to better understand glucose patterns among people without diagnosed diabetes. The study began in 2022 and has had more than 35,000 participants. Here are some highlights from what we’ve seen in our data so far.

Post-Meal Glucose Levels

Breakfast

- Average Glucose for 2 hours post meal = 105.96 mg/dL

- Average Minutes Above range (70-110)= 47.67 minutes

- Glucose Delta: 20.69 mg/dL (difference between highest and lowest glucose reading during the zone)

Lunch

- Average Glucose for 2 hours post meal = 107.8 mg/dL

- Minutes Above range (70-110) = 57.64 minutes

- Glucose Delta: 36.8 mg/dL

Dinner

- Average Glucose for 2 hours post meal =107.18 mg/dL

- Minutes Above range (70-110) = 59.96 minutes

- Glucose Delta: 28.24 mg/dL

Mean time to post-meal glucose peak was between 46 and 50 minutes.

Waking Glucose

Waking glucose approximates your fasting glucose levels, a measure of your blood sugar levels unaffected by a recent meal. It looks at the average in the hour before waking to avoid being impacted by the dawn effect, a natural rising of blood sugar when you wake up.

Mean waking glucose: 107 ± 16.47 mg/dL

Dawn effect: Levels members experience an average dawn effect of 7.05 ± 9.95 mg/dL (Grouped by member)

Time in Range

This describes the amount of time members stayed between 70–140 mg/dL for an average of the day.

People spend an average of 64.58% of day (± 31.35%) under 110 mg/dL

- 7% of glucose values were >140 mg/dL.

- 1.6% of glucose values were <70 mg/dL.

- .1% of glucose values were <50 mg/dL.

- Participants spent ~80% of the time between glucose values 59-100 mg/dL and 20% of the time between 100-140 mg/dL.

Daily Glucose Metrics

Mean 24-hour glucose levels were 106 mg/dL (± 19 mg/dL).

- Mean daytime glucose was 106 ± 11 mg/dL. (Between 5am and 7pm)

- Mean nighttime glucose was 99 ± 11 mg/dL. (Between 7pm and 5am)

- Mean overnight glucose was 99 ± 11 mg/dL. (Between 11pm and 4am)

- Maximum daily glucose levels were an average of 149.68 mg/dL (± 22.08 mg/dL).

- Out of the 35,407 participants, 7.2% of members averaged a diabetic response to lifestyle activities of a max glucose greater than 180 mg/dL

Summary Of Normal Glucose Ranges

In summary, based on ADA criteria, and the IDF guidelines, a person’s glucose values are “normal” if they have fasting glucose <100 mg/dL and a post-meal glucose level <140 mg/dL. Taking into account additional research performed specifically using continuous glucose monitors, we can gain some more clarity on normal trends and can suggest that a nondiabetic, healthy individual can expect:

- Fasting glucose levels between 80-86 mg/dL

- Glucose levels between 70-120 mg/dL for approximately 90% of the day (and rarely ever go above 140 mg/dL or below 60 mg/dL)

- 24-hour mean glucose levels of around 89-104 mg/dL

- Mean daytime glucose of 83-106 mg/dL

- Mean nighttime glucose of 81-102 mg/dL

- Mean post-meal glucose peaks ranging from 99.2 ± 10.5 to 137.2 ± 21.1 mg/dL

- Time to post-meal glucose peak is around 46–60 minutes

These are not standardized criteria or ranges but can serve as a simple guide for what has been observed as normal in people without diabetes.

Beyond “normal” goals: What’s an “optimal” glucose level, and why does it matter?

Exact numbers for what is considered “optimal” glucose levels to strive for while using CGM to achieve your best health are not definitively established; this question is individual-specific and should be discussed with your healthcare provider. With that said, research shows an increased risk of medical conditions and problems as fasting glucose increases, even if it stays within the conventional target range, making finding your “optimal” glucose levels all the more critical.

While the International Diabetes Federation and other research studies have shown that a post-meal glucose spike should be less than 140 mg/dL in people without diabetes, this doesn’t determine what value for a post-meal glucose elevation is optimal for your health. All that number tells us is that in nondiabetics doing an oral glucose tolerance test, researchers found that these people rarely get above a glucose value of 140 mg/dL after meals.

So, while this number may represent a proposed upper limit of what’s “normal,” it may not indicate what will serve you best from a health perspective. Many people may likely do better at lower post-meal glucose levels. Similarly, while the ADA states that a fasting glucose less than 100 mg/dL is normal, it doesn’t indicate what value is optimal for health.

Lastly, there are no specific recommendations regarding the average blood sugar levels over 24 hours using CGMs. This lack of standardization is likely because CGMs, which enable continuous blood glucose monitoring, are relatively new and not widely used in a nondiabetic population.

“Repeated high glucose spikes after meals contribute to inflammation, blood vessel damage, increased risk of diabetes, and weight gain.”

The following is a summary of insights from our review of the research. You should consult your doctor or healthcare team before setting glucose targets or implementing dietary and lifestyle changes.

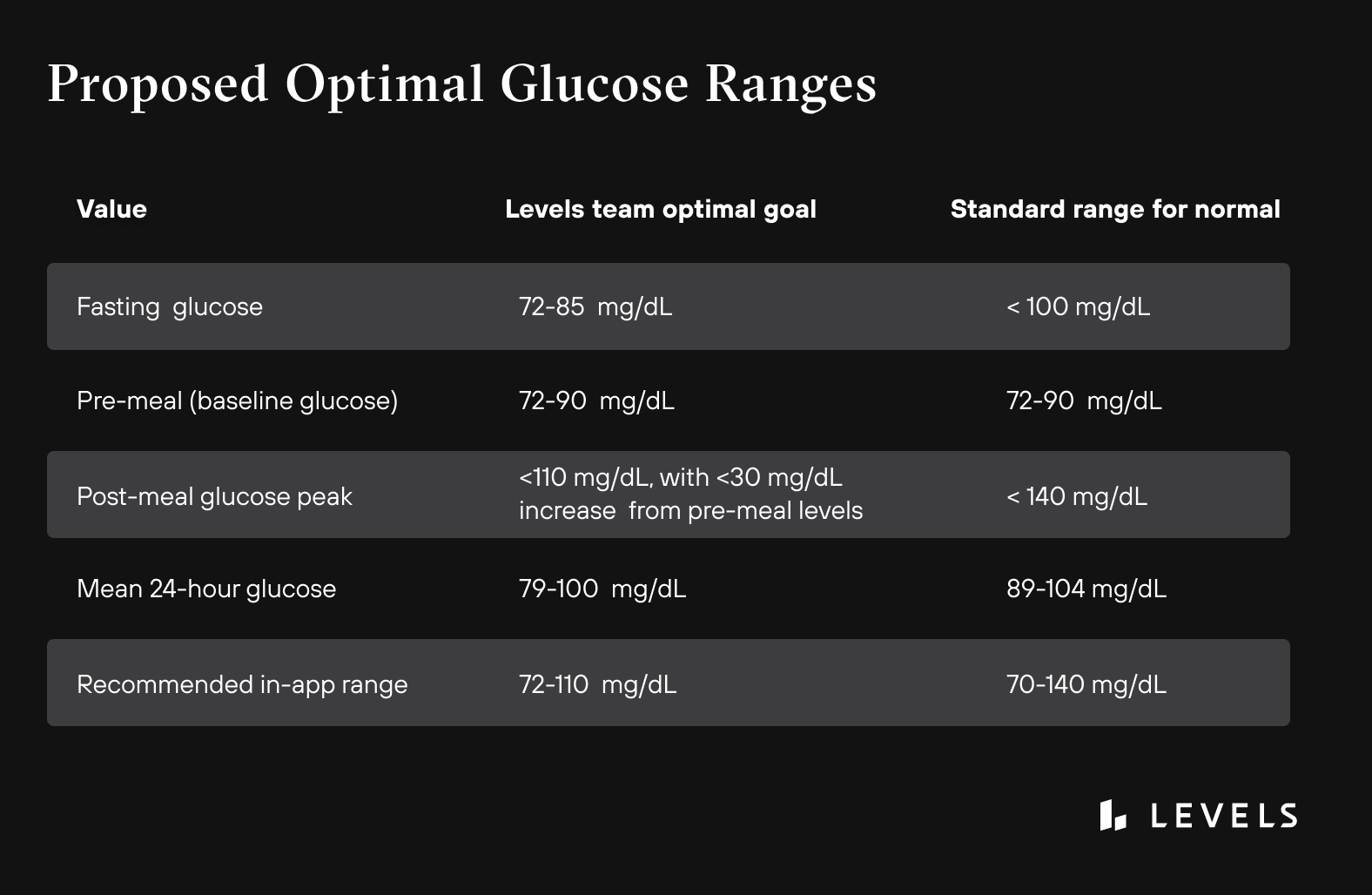

Levels Proposed Optimal Glucose Values

Fasting Glucose Goal: 72-85 Mg/dL

Why? Previously, we discussed that the ADA considers normal fasting glucose as anything <100 mg/dL. However, multiple research studies show that as fasting glucose increases, there is an increased risk of health problems like diabetes and heart disease — even if it stays within the normal blood sugar level range. The highlights of some of the study results include:

- Men whose fasting blood glucose was greater than 85 mg/dL had a significantly higher mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases than men with blood sugars less than 85 mg/dL. (Bjornholt et al.)

- People with fasting glucose levels in the high normal range (95-99 mg/dL) had significantly increased cardiovascular disease risk than people whose levels remained below 80 mg/dL. (Park et al.)

- Children with fasting glucose levels of 86-99 mg/dL had more than double the risk of developing prediabetes and Type 2 diabetes as adults compared to children whose levels were less than 86 mg/dL. (Nguyen et al.)

- People with fasting glucose levels between 91-99 mg/dL had a 3-fold increase in Type 2 diabetes risk compared to those with levels less than 83 mg/dL. (Brambilla et al.)

- Among young, healthy men, higher fasting plasma glucose levels within the normal range constitute an independent risk factor for Type 2 diabetes. This means that as fasting glucose increases, even if the level is still considered “normal,” it could indicate a significantly higher risk of developing diabetes, and this is particularly pronounced if BMI is greater than 30. (Tirosh, et al.).

Pre-Meal (Baseline) Glucose Goal: 72-90 mg/dL

Why? In a study looking at healthy, young, adults without diabetes who had normal BMI (mean of 22.6 ± 1.7 kg/m2), the average pre-meal glucose levels were in the range of 72-90 mg/dL.

Post-Meal Glucose Goal: Less Than 110 mg/dL, With No More Than A 30 mg/dL Increase From Pre-Meal Levels

Why? In a study looking at healthy adults without diabetes, researchers found that the average post-meal glucose peak was 99 ± 10.5 mg/dL after a standardized balanced meal. In contrast, meals with less fiber and more refined sugars caused a higher post-meal glucose spike (up to an average of 133 ± 14 mg/dL) in the same population. Another study also looking at healthy, nondiabetic adults found an average post-meal spike of approximately 122 ± 23 mg/dL. Considering the standard deviation of these averages, aiming for a post-meal glucose level of less than 110 mg/dL with no more than a 30 mg/dL increase from pre-meal levels is a reasonable goal.

Mean 24-Hour Glucose Goal: 79-100 mg/dL

Why? These numbers represent the mean 24-hour glucose range in a young, very healthy population. We looked at several studies of people without diabetes wearing CGMs, and this was one of the overall healthiest populations under normal living conditions. Therefore, we think that 79-100 mg/dL is a safe and healthy range to orient towards.

Remember, your “optimal” glucose levels are specific to you, and you should talk with your healthcare provider about your glucose goals.

How can CGM help you maintain optimal glucose levels?

It is common for your glucose levels to increase after a meal: you just ate food that may contain glucose, and now your body is working on getting it out of the bloodstream and into the cells. We know that we want to prevent excessive spiking of glucose levels because studies show that high post-meal glucose spikes over 160 mg/dL are associated with higher cancer rates. Spikes are also associated with heart disease. Repeated high blood glucose spikes after meals contribute to inflammation, blood vessel damage, insulin resistance, increased risk of diabetes, and weight gain. Additionally, the data shows that the big spikes and dips in glucose are more damaging to tissues than stable high blood sugar levels. Therefore, you should strive to keep your glucose levels as steady as possible, at a low and healthy baseline level, with minimal variability after meals.

Keeping your glucose levels constant is more complicated than just following a list of “eat this, avoid that” foods. Each person has an individual response to food when it comes to their glucose levels; studies have shown that two people can have different changes in their glucose levels after eating identical foods. The difference can be pretty dramatic. One study found that some people had equal and opposite post-meal glucose spikes in response to the same food.

So, how do you keep your glucose levels stable? How do you know when you have a sugar spike and which foods cause it? That’s where CGM comes into play. Continuous glucose monitoring allows you to see your blood glucose levels in real time and store that data for future reference; this makes CGMs uniquely positioned to help you optimize your diet and lifestyle. Foods affect each person differently, and it is hard to know what your blood glucose is doing at any one time without measuring it. CGMs can give you the data you need to optimize your health. Choosing foods and lifestyle habits that consistently keep average glucose lower and post-meal spikes lower will improve glucose patterns over time.

Studies have shown that the information gathered from CGMs can provide more detail and potential areas for modification than the single glucose level you get with a glucose meter (glucometer) or from a blood sample at a laboratory blood test. One study looked at sub-elite athletes and found that 4 out of 10 study participants spent more than 70% of the total monitoring time above healthy glucose levels, and 3 of 10 participants had fasting glucose in the prediabetic range.

Similar results have been found in other studies: one reported that 73% of the “healthy” nondiabetic participants had glucose levels above normal in the range of 140-200 mg/dL at some point during the day.

CGMs can not only give you data on your blood glucose, but they can help you use the data to make changes to your diet and physical activity routines. Studies have shown that continuous glucose monitoring can characterize an individual’s glucose response to specific foods and, in turn, predict their responses to other foods. This technology can allow people to create personalized meal plans that suit their unique metabolic needs and improve glucose control.

What are abnormal glucose levels, and why do they matter?

Why is it unhealthy for glucose levels to be too high (hyperglycemia) or too low (hypoglycemia)?

Hyperglycemia refers to elevated blood glucose levels. This usually occurs because the body does not appropriately remove glucose from the blood; this can happen due to many complex reasons. Elevated glucose levels can damage blood vessels and nerves over time; this can then lead to problems in the eyes (and sometimes even vision loss), kidneys, and heart, as well as numbness in the hands and feet. Very high levels can lead to coma and even death in some cases. People with fasting glucose levels higher than 100 mg/dL have impaired glucose tolerance and should speak with their healthcare provider.

Some people may think that to avoid all these issues, they should just keep their blood glucose levels as low as possible. If too high is bad, then low blood sugar must be good, right? Not exactly. When glucose gets too low, it’s called hypoglycemia. The threshold for hypoglycemia is typically thought to be when glucose falls below 70 mg/dL. When this happens, the body may release epinephrine (adrenaline), the “fight or flight” hormone, which can lead to a fast heart rate, sweating, anxiety, blurry vision, and confusion, but also helps the body mobilize glucose into the blood. If blood glucose levels stay too low for too long, it can cause seizures, coma, and, in very rare instances, death.

The Nuances Of Low Glucose

In a recent study, researchers reviewed the published literature to see if low fasting glucose levels affected healthy people’s long-term risks of health problems like strokes and heart attacks. They found that healthy nondiabetic people who had baseline fasting glucose levels of less than 72 mg/dL had a 56% increase in all-cause mortality compared to people with normal fasting blood glucose levels. Also, the risks for heart attacks and strokes were higher in people with baseline fasting glucose levels less than 72 mg/dL. This result is likely due to the body releasing more epinephrine to counteract the low glucose levels; too much epinephrine for too long leads to heart problems. Interestingly, people with low fasting glucose levels of less than 83 mg/dL but higher than 72 mg/dL did not have an increased risk of future heart attacks and strokes.

While there has been an association between low fasting plasma glucose levels and worse health outcomes, it is unclear whether transient dips in glucose levels (less than 70 mg/dL) during a continuous 24-hour period are unhealthy for people without diabetes. This is partly unknown because continuous glucose monitoring is a relatively new technology and has been studied more extensively in people with diabetes than in those without.

Long-term health outcomes relating to 24-hour glucose profile metrics are still being evaluated. In one study looking at people without diabetes wearing CGMs over a 24-hour period, data showed that glucose dips below 70 mg/dL actually occur quite frequently. In fact, 41% of these healthy people experienced glucose levels less than 70 mg/dL in a 24-hour period, and the men’s levels were below 70 mg/dL for 2.7 +/- 6.1% of the 24-hour period (2.1 +/- 4.4 % in women). Based on this data, healthy people can reasonably spend an average of 39 minutes with glucose values less than 70 mg/dL (in men). Furthermore, considering one standard deviation higher than the average, it could reasonably be considered “normal” to spend up to 126 minutes (8.8% of a 24-hour period) with CGM-measured glucose values less than 70 mg/dL. The clinical significance of these low glucose levels is unknown. Still, research suggests that many healthy people wearing CGMs spend some time with glucose levels less than 70 mg/dL.

Research also shows that glucose levels decrease by an average of 5% during REM sleep compared to non-REM sleep stages, which may contribute to periodic dips seen at night in nondiabetic people. In fact, healthy people who have glucose dips below 70 mg/dL have twice as many dips at night as compared to during the day. Additionally, pressure on the CGM sensor from laying on it can cause aberrant low values.

Lastly, glucose dips below 70 mg/dL that occur just after a post-meal glucose spike may indicate reactive hypoglycemia, which is an exaggerated insulin response to a high carbohydrate meal, causing an overshoot in the amount of glucose that is absorbed out of the bloodstream and into cells and is not good for health. Again, we don’t want high highs and low lows; stable glucose appears to be better for the body. These glucose dips are typically characterized by symptoms including fatigue and lack of energy. They can be avoided by a low-carb/low-glycemic eating pattern with reduced post-meal glucose spikes.

Even though there is no defined low point for nondiabetic fasting blood glucose levels, keeping your blood glucose levels above a minimum threshold of 72 mg/dL may be beneficial for healthy, nondiabetic people.

Conclusion

What does all this mean? It means that while there are well-established “normal” ranges of fasting and post-meal glucose levels, these don’t give clarity into what glucose trends should be throughout a 24-hour period. They also don’t specify what ranges are optimal for the best health.

Even people with “normal” glucose levels may be at higher risk of health problems than they realize because of frequent glucose spikes and dips or elevated fasting glucose, even if in the normal range. Your optimal glucose levels depend on many factors, and setting those ranges should include a discussion with your healthcare provider.

The studies show that keeping your blood glucose in the normal range is essential, but also that preventing too many spikes and dips is key to maintaining your health. A personalized dietary and lifestyle plan that promotes metabolic health should also accomplish three main goals:

- Minimize post-meal increases in glucose levels

- Keep glucose levels as stable as possible and minimize swings in glucose throughout the day

- Try to keep fasting glucose at the low end of the “normal” range

Figuring out which diet and lifestyle choices will allow you to achieve these goals is an iterative process; no one-size-fits-all plan works for everyone to keep blood glucose in their optimal range. Continuous glucose monitoring can help you establish your optimal diet and lifestyle choices by serving as a continuous feedback mechanism, closing the loop between specific actions and the body’s reaction, and paving the way for improved current and future health.

Want to learn more about your glucose levels?

Want to learn more about your glucose levels?