Dr. Sara Gottfried is a pioneer in health. She’s a physician-scientist who graduated from Harvard Medical School and MIT and completed her residency at the University of California, San Francisco. She specializes in identifying the underlying causes of conditions, not just symptom management. It’s not one-method-fits-all, it’s not disease-centered, it’s a mission to transform healthcare one patient at a time.

She’s currently the director of Precision Medicine at the Marcus Institute of Integrative Health at Thomas Jefferson University and her research focuses on metabolic phenotyping. She’s also the Principle Investigator of a research project sponsored by Levels to study early biomarkers of the transition from health to prediabetes.

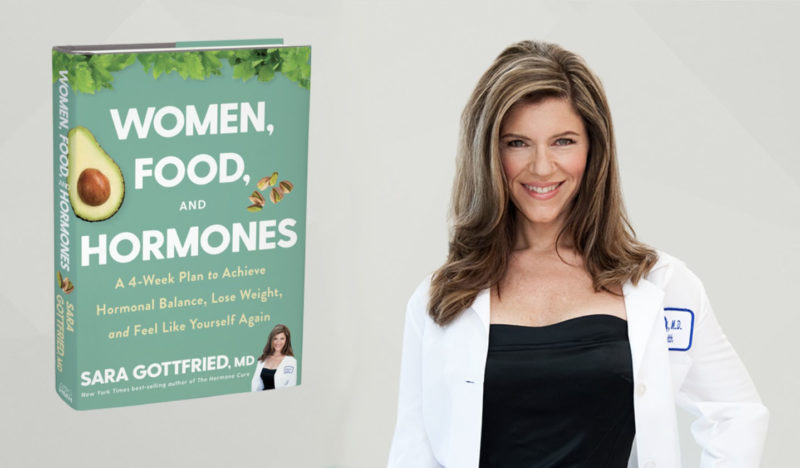

Dr. Gottfried has published several New York Times bestselling books, including The Hormone Cure, The Hormone Reset Diet, Younger, and her new book, Women, Food and Hormones.

Levels co-founder and chief medical officer Dr. Casey Means recently interviewed Dr. Gottfried on an episode of our podcast, A Whole New Level. The following is an edited version of that conversation.

On why we should all pay more attention to metabolic health …

Dr. Casey Means: Let’s just jump in with really the big picture: Why should the average person care about metabolic health? Why should someone who doesn’t have prediabetes or Type 2 diabetes be concerned about their glucose tolerance and things like metabolic flexibility?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: Metabolism is the foundation of your health today and tomorrow. Many people misconceive the word metabolism. They think that it’s related to their weight, or maybe how much belly fat they have. The truth is that the concept of metabolism is so much deeper and broader than that. Metabolism is the aggregate of all of the biochemical processes that are occurring in the body. That includes the metabolic hormones, like insulin, cortisol, leptin, testosterone, growth hormone, and dozens of others. Metabolism drives so many factors when it comes to health and how you feel today, and how you’re going to age over the next few decades.

Dr. Casey Means: I agree. Our metabolism is our engine, and it allows us to do the things that we want to do, and really embody that vision we have for our lives. Without a well-functioning way of making energy in the body, it’s going to be very difficult to enact that vision and make it a reality.

It also relates to what’s happening with COVID right now. We’re seeing that a big determinant of outcomes in relation to this virus has to do with our underlying metabolic health. And that it really is time for each person to make that decision individually to take control of their metabolic health, because that is, in my opinion, one of the best ways that we can support our communities and our families, and boost our resilience in the face of this monumental threat.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: Yes, there’s an epidemic within the pandemic, and that epidemic is metabolic dysfunction. It’s not like this virus just happened upon us and we’re innocent victims who fell prey to this virus. We’ve been meeting this virus in the middle for a long time in terms of what we’ve done with our metabolic health.

You connected metabolism to mental health. I appreciate that point because we know, looking at the research over the past year and a half, that depression has tripled during the pandemic. We’re finally at a point of realizing that metabolism is not something that we outsource to the internist or only talk about with our family doctor. We need to democratize these data so that people have access to it, and to connect these dots so that even psychiatrists realize that metabolic health is a tool in their toolbox. This is so important in terms of anxiety, depression, suicide, some of these other factors that really have been unveiled and unmasked by the pandemic.

On improving metabolic health and why keto diets often don’t work for women …

Dr. Casey Means: With that, how do we improve our metabolic health?

You just wrote an incredible book—Women, Food, and Hormones—that’s really the ultimate guidebook for helping women, especially, achieve their wellness goals by optimizing metabolism.

In the book, you talk specifically about low carbohydrate diets and why a traditional ketogenic diet may not work as well for women as it does for men. Can you explain why the standard ketogenic diet can be counterproductive in some women when done in the traditional way, and perhaps other frameworks for tailoring it for women to be more effective specifically?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: My books arise from listening deeply to patients in my medical practice (I run precision medicine at the Marcus Institute of Integrative Health at Thomas Jefferson University). I noticed about eight years ago that I was suddenly seeing keto refugees. I was especially seeing women who would go on a ketogenic diet with their male partners or with colleagues from work. The men would do very well with fat loss and metabolic health, and the women would hardly notice a change. Maybe they even felt more inflamed or gained weight. They maybe had other downstream consequences that are important to list because you often don’t hear them from some of the keto thought leaders. Outcomes like 45% of women in some studies have menstrual irregularity, some have thyroid dysfunction with increased reverse T3, some experience high cortisol levels, and cortisol is key part of metabolic health.

“Women are not just small versions of men; they’re not men with breasts. We are quite complex and different, both in terms of sex differences and gender differences. What works for men doesn’t necessarily work for women.”

Many had sleep issues, because, for some women, the ketones produced by a ketogenic diet can be very activating. That can be a good thing for your brain when mitochondria start to falter in the female brain after 40. A lot of people, when they’re on a ketogenic diet, feel like they hear the angels singing. They have mental acuity that feels delightful. And yet that can backfire and make it very hard to unwind at night. We know that women have about double the rate of insomnia compared to men.

When I see results like that, I do two things: I go to the literature to see what the science tells us, and then I try it myself in an N-of-1 trial design.

When I went to the literature, I found that most of the data were on men. Approximately 80% of the metabolic studies were in men only. Of course, we have biases across the board in scientific evidence— that women are considered too complicated to study, especially women who are menstruating and have hormonal variations. But women are not just small versions of men, they’re not men with breasts. We are quite complex and different, both in terms of sex differences and gender differences. What works for men doesn’t necessarily work for women. When I saw this bias in the literature, I tried the keto diet myself. And I failed.

I failed the first few times, and in various several ways. Until I got the protocol tweaked for women, I didn’t correct my longstanding prediabetes. I didn’t lose weight. By some measures, my inflammation got worse. I didn’t get the metabolic flexibility that I was hoping to get. (I found in retrospect that there are some genomic drivers involved with this.) I wasn’t processing the saturated fat—the bacon, the cheese, the steak— in a healthy way.

This got me to adjust the protocol, because in precision medicine, we love to do N-of-1 experiments, where each person serves as their own control. It’s what I do with patients, it’s what I do with myself. I’ve got a constant N-of-1 experiment occuring.

What I discovered is that my success with the ketogenic diet depended on several factors: if I had my detox pathways fully open, if I was methylating properly, if I was getting the whole foods that I needed—especially the cruciferous vegetables rich in sulforaphane that help phase 2 of liver detox, as well as the allium vegetables that helped me produce glutathione—together these foods helped me detoxify and respond better to keto.

If effective detoxification was in place before starting a ketogenic diet, it was much more effective for me. This is anecdotal evidence but it also isn’t about me. What I want to do is to determine what sets both men and women up for success. I started to experiment with my patients, with their permission. I included cases in the new book of people who were successful with keto, even super responders, as well as people who just lost a small amount of weight, but the protocol still had a significant impact in terms of metabolic flexibility.

There’s a keto paradox in the literature—and may be interpreted a few ways. First is the notion that what works so well for men, doesn’t work as well for women when it comes to nutritional ketosis. We want to pay attention to those differences, not just gloss them over. Understanding these sex and gender differences really helps all of us, not just women. The second keto paradox is that some cancers respond well to the ketogenic diet, the pleiotropic role of ketones, and lower insulin and glucose, but that is not true across the board. We need more clinical research, such as the work of Sid Mukkherjee MD at Columbia University, which you can read more about in the New York Times. For that reason, I always recommend that patients with cancer or a history of cancer consult their treating physicians for information on whether a ketogenic diet is safe for them. Third, some people and laboratory animals become more insulin resistant on the ketogenic diet, which I found when I first tried it in 2016. I discovered that I have a few genetic variations that are associated with greater insulin resistance in response to saturated fat, so when I went keto with more plant-based fat, my metabolic health improved. There are paradoxical qualities of the ketogenic diet that we need to understand better.

On plant-based diets and why she is food agnostic …

Dr. Casey Means: I am plant-based, and there’s this idea that you can’t be plant-based and also get into ketogenesis, which is not true. I woke up with ketones of 2.0 this morning. I did just do a 36-hour fast, but it is possible to balance these worlds. One of the things that drives me in being plant-based is the detoxification, the plant chemicals that I’m trying to get into my body to optimize my liver pathways, my phase 1 and phase 2 detoxification, my glutathione production, and my microbiome through the impact of fiber and other phytochemicals to improve my elimination.

And if we’re slowing those things down by eliminating a lot of these nutrient-rich foods on what might be a more traditional ketogenic diet, there’s going to be potentially downstream effects.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: You raised so many important points and I want to highlight a few of them. When I first asked the question, “What is the diet that provides the best metabolic function?” I found that it’s whole foods, 100% plant-based. There’s a lot of scientific evidence behind this. And when I followed that food plan, I didn’t do that well, it didn’t actually help me with metabolic flexibility.

That brings up the essential role of personalization. Even though there’s literature that at a population level, whole foods and 100% plant-based is one of the most healing in terms of metabolism, it didn’t work for me. This is the personalization that we really need in medicine going forward.

Some of the drivers in my case relate to a history of disordered eating. I have a type of energy regulation and genomic pathways that are associated with difficulty with satiety, so I have a high appetite and difficulty feeling full. It takes a lot of food for me to feel sated. So I eat too much when I am plant-based. What I found with the ketogenic diet is that the production of ketones helps me with satiety—that was the missing piece for me when I combined it with detoxification. I’m not saying everyone should go on a ketogenic diet. We have to personalize and figure out what’s best for the individual.

Dr. Casey Means: Right. Someone might listen to this and say, “Oh, well, her ketones are up with a plant-based diet. So that means I can just eat a plant-based diet and my ketones will rise.” That is not the case at all. It’s been two years of dialing in, with a continuous glucose monitor, exactly what plant-based foods work for my body and don’t cause a glycemic excursion, how to pair foods to keep the glucose levels flat, how to incorporate intermittent fasting to see the numbers change. Having that data and that feedback to tailor your diet can be so helpful.

A great point is that you can achieve ketogenesis or metabolic flexibility, I think, from almost any dietary philosophy, and those different dietary philosophies are going to work for different people’s bodies based on many of the things you talked about, like genetics and history.

For me, the outcome I want is metabolic flexibility. And to know that my body’s pathways to make ketones—burn both fat and carbs, not just carbs—that those pathways in my cells are working. And so that feedback loop of trying different things out can create the personalization of this particular philosophy that seems to work well for my body.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: I would say part of what you and I are expressing here is that we’re food agnostic.

You have found what works for you, I found what works for me. They’re not exactly the same because we’ve personalized them. Often we can get into this state of tribalism around food. It’s almost like talking about religion or politics. But it’s not that you have to eat a particular way. I have a lot of patients who were cases for the book who were vegan. I had patients that were vegetarian. I had patients who were on the carnivore diet before they came to me and we started this protocol. So I just want to say here that we are food agnostic and I hope that comes across in the work that I put out into the world.

Levels Member Experience:

On incorporating intermittent fasting and optimizing keto

Dr. Casey Means: In a chapter of the book called The Keto Paradox, you talk about how incorporating intermittent fasting can allow people to stay in mild ketosis while having a slightly higher carbohydrate intake than what would be allowed on a standard ketogenic diet. I’d love to hear more about how intermittent fasting can serve as a bit of a buffer to allow women who may need to eat slightly more carbohydrates, for optimal functioning, to still be able to achieve ketogenesis.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: What’s lovely about intermittent fasting is that it’s programmed into our DNA. Our DNA is designed to have these periods of metabolic rest. It’s how our ancestors evolved depending on the seasons, depending on food scarcity, and what was available.

I think of intermittent fasting as a back door to ketosis, as you described with the fasting that you did, how it raised your ketones to 2.0. What we know is that intermittent fasting is a way to tolerate more carbohydrates. So with classic keto, what typically happens is that people go on a 70-20-10 macronutrient ratio, where 70% of the calories are from fat, 20% from a moderate protein diet, and then 10% from carbohydrates. I’ve found that for some women, that’s just not enough carbs, especially women who are more stressed or have high perceived stress. And I’m talking now to a lot of those women between the ages of 30 and 55. And I say that with so much love because I’m one of them.

Based on the amount of exercise and the amount of stress that you have, the number of carbs that you need varies. So being able to personalize that is helpful. There’s a particular sequence that I found to be most advantageous in these N-of-1 experiments in the research that I did on a ketogenic diet adapted to women.

The first is detoxification, really make sure that those pathways are open by the mechanisms that we just talked about. Then, second, a ketogenic diet. But I like to go by net carbs, not total carbs, because that lets us pay attention to those prebiotic fibers that are so important for metabolic hormone balance.

The third piece is to layer in fasting, but not to do it in such an aggressive way that you’re raising cortisol, because cortisol is one of those hormones that can really crash the party and cause metabolism issues. Right now, my take on the scientific literature, after looking at thousands of studies, is that somewhere around a 14-hour overnight fast is probably the most healing in terms of downstream signaling, changes in hormones, changes in metabolomics, without triggering a cortisol spike. Other people like a longer fast. When I first started, I was doing a 16/8 protocol because that’s what a lot of the science supported—though, again, most of it in men.

Some people like to fast 24 hours or even longer. We know that can be stressful for some. But 14 hours is where I start with my patients. For most people, depending on your metabolic flexibility, somewhere around a 14- to 18-hour overnight fast is where you start to produce ketones. Intermittent fasting is a back door to ketosis. Once again, there are sex differences: men tend to produce ketones sooner in a fast.

Dr. Casey Means: That concept of fasting as a potential stressor is such an important point. I often get asked by patients if fasting is too much for women at certain points in their life, like if there’s already a lot of stress going on, or if they are training for a race or in a particular part of their menstrual cycle. What’s your framework for thinking about when people should dial this up and when people should dial it down, if at all?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: What I like to do is to test, so this gets us back to the N-of-1 study. I look at different factors of stress and cortisol. And there are many proxies for this, such as heart rate variability, which you can track with devices like an Oura Ring. My general advice is to really develop interoception, that sense of what’s going on in your body, and being in tune with it. It’s something that was stamped out of us when we went through our medical training, when we couldn’t eat when we needed to eat, couldn’t go to the bathroom when we needed to, couldn’t sleep when we needed to. A lot of us have a broken feedback system and can’t really tell what’s stressful. Our set point is so high with cortisol and stress. Sometimes having these other sensors can be very helpful in getting back that interoception.

On the effect of menstrual cycles on performance and nutrition …

Dr. Sara Gottfried: Menstrual cycles are an infradian rhythm that women benefit from considering, particularly with regard to gains and metabolism. I take care of a lot of athletes, including NBA players and Olympians. The ideal time to fast and also to go for gains is right around day 9 through 14 of a menstrual cycle. That’s when testosterone is at its peak for women who are still cycling.

Estradiol tends to peak around day 12. (This is based on a hypothetical 28-day cycle, which not everyone has.) When you want to go for muscle gains, personal bests, or speed trials, that’s the best timing.

The worst time of the cycle is late luteal. Right around day 20 to 28, which is when progesterone peaks, you get another small peak of estradiol, but you’ve got that estrogen-progesterone tango happening, that’s where women tend to have much more in the way of carb cravings and may even pop out of ketosis.

In studies looking at women in the wild, they eat about 260% more refined carbohydrates in the late-luteal phase. That’s a time it can be harder to fast. I like to set people up for success. You can do a very slow on-ramp to fasting, but for those who are still cycling, I would advise focusing on that period of time from day 9 until 14. That’s where most women find intermittent fasting the easiest.

On the role of testosterone and growth hormone in women and metabolic health …

Dr. Casey Means: You talk about some hormones that I don’t think we normally think about very often in the context of metabolic health, including testosterone and growth hormone, which just are not buzzwords in this field, especially when it comes to women. Why are these hormones important for our overall metabolic health, and how can we keep them in balance?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: Let’s start with testosterone. Testosterone is interesting because it’s thought of as the male hormone. Folks don’t realize that it is the most abundant hormone in the female body. Yes, men have 10 to 20 times more testosterone than women do, but it’s our most abundant hormone. We are exquisitely sensitive to it.

Most of the literature on metabolic health and testosterone is from men. The low T syndrome that we see in men is associated with metabolic dysfunction—more diabetes, more dysglycemia, more insulin resistance. Women are a little more dynamic. With women, we want testosterone to be in that Goldilocks position—not too high, not heading in the direction of polycystic ovary syndrome, but also not too low. Low T in men has many parallels to high T in women.

Testosterone declines in both men and women starting in their 20s. Your peak is typically around 20 to 28. There’s about a 1% annual decrease in testosterone production as you get older, and that can be accelerated by high perceived stress, high cortisol, and high refined carbohydrates (bread, pasta, etc.). That was my story—I’m always learning from my own experiments. Low T is a common root cause in fatigue, lack of muscle response to exercise, decreased libido, and metabolic dysfunction. If you’re consistent about exercising but just not seeing a response, it could be related to low testosterone. It’s also involved in confidence, risk taking, and agency in women. There is a study in female MBA students showing that women who have higher testosterone are more likely to be comfortable with risk.

Growth hormone is one that I didn’t pay a lot of attention to through my medical training. It does what the name implies: It helps with growth and repair. It’s responsible for height when you’re a child.

But it has continued roles into adulthood, including in insulin function and belly fat, visceral fat. There’s also significant sex difference here. (Sex differences are biological whereas gender differences are sociocultural constructions.) Women tend to make growth hormone more continuously, whereas men tend to be more pulsatile with longer periods between their pulses of growth hormone. Most of the pulses occur at night.

Women actually make more growth hormone than men until they go through menopause. Then we make much less and a lot of women notice that difference. They have more fatigue, they have more belly fat, they notice this redistribution of their fat deposits. Their clothes just don’t fit quite the way that they used to even if their weight is the same. There are a lot of hormones involved in that, not just growth hormone, but also insulin, estrogen, testosterone.

The reality is that there are dozens of hormones that play metabolic roles. The key is to figure out which are the main drivers for you. And then how to use diet, nutrition, and lifestyle to make healthy changes.

On testing for hormone levels and overall metabolic health …

Dr. Casey Means: I can imagine people are thinking, “Oh gosh, how do I know where I’m at with these? And are there things associated with keeping these in the right balance?” Are these tests that you recommend people asking their doctor for?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: Start with the questionnaires in my new book. These are the same questions I ask patients in my precision medicine practice. For testing, I think we all deserve a metabolic panel, but you also don’t have to assign the role of gatekeeper to your physician to improve things.

I practice precision medicine. I like to measure things. I find that it helps me step into action and holds me accountable. But one of the things you may hear from your doctor is, “We don’t check those hormones. They fluctuate too much.” And yet, if you’re 32 and trying to get pregnant, they’ll check all those hormones. If you’re having trouble conceiving, they’ll check your thyroid, cortisol, testosterone, estradiol, progesterone.

That is a double standard to be told that it fluctuates too much and it’s not meaningful when you’re not trying to get pregnant and yet it is meaningful if you are trying to get pregnant.

It brings up a larger point that we’re dancing around, which is that role of the physician as gatekeeper because that’s part of how we got it into this big mess metabolically.

How much time do you actually spend with your doctor? I spend less than 1% of my time. I mean, it’s more like 0.001% of my time. The other 99.99% of my time is me doing these experiments outside of the doctor’s office. Why would I want to outsource my metabolic health to an annual measurement of my fasting glucose and my hemoglobin A1C? It’s important to democratize this data so that we can do these types of experiments that allow us to improve metabolic health.

I heard Levels CEO Sam Corcos say in an interview that part of his discover was that the oatmeal and orange juice he had daily as part of a presumed healthy breakfast were spiking his glucose quite severely and causing problems with his metabolic health. I’m paraphrasing but he said that initially he thought the problem to solve was ignorance. But what he realized is that it’s not ignorance, it is misinformation. I think what he’s getting at with “misinformation” is the way that we, as consumers, are kept at arm’s length from our data and given advice that’s been influenced by poor quality nutritional studies and even Big Pharma. The more that we have that data at our fingertips to empower us to make decisions, the better.

On diagnosing prediabetes and metabolic dysfunction …

Dr. Casey Means: We have 90 million people in the United States meeting criteria for pre-diabetes and about 85% of them do not know that they have it. Looping back to COVID, this is very much related to the outcomes that we’re seeing in this pandemic. But not just that, people are walking around, living their lives, not feeling great, and yet feel a lot of trust in this system that says, “Oh, you came in last year and your glucose was 102 milligrams per deciliter. So you’re just right on the cusp and nothing to worry about. It’s fine.” Even though we know that’s low prediabetic range, which means that metabolic dysfunction is in full force and has probably been going on for over a decade.

But the tests, in the way that we look at this, do not capture that and don’t really give any power to the individual to really make changes. So I would love to dig into the work that you’re doing on multiomic phenotyping of prediabetes and how this could potentially open up a new understanding of the development of the disease, and how we think about diagnosing it much earlier.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: I appreciate that example of someone with fasting glucose of 102 because that was me when I was 35. I remember I got my fasting glucose back and I pinged my primary care doctor, who told me, “Oh, you’re fine. Stop drinking juice.” I don’t blame that guy because I wasn’t taught much in the way of nutrition when I went through my medical training, it’s the thing I had to teach myself.

But this is something I love to do at parties. I ask people, “Hey, what’s your fasting glucose?” And most people have no idea. Occasionally I’ll have a taker who will look it up on their iPhone, get into their electronic health record portal, and say, “Oh, I was 105. That’s pretty good, right?” And I tell them “No.”

The other issue is that the gold standard for checking metabolic health in conventional medicine is a fasting glucose test, maybe an A1C, once a year. This is the tiniest little blip of time to see what’s going on with metabolic health. You’ve got a needle in the vein for 30 seconds. But what was going on with your sleep last night? What did you eat yesterday? How much exercise did you have? Did you exercise this morning before you gave a fasted sample? Now we have the capacity and the power to get much more dense and comprehensive data.

That includes continuous glucose monitoring, but you don’t even have to buy a CGM. You could get a little glucose meter from the drugstore and look at your fasting glucose over time. You could do N-of-1 experiments. You could do one-hour postprandial glucose as part of seeing what carbs you respond to and what food is the best for you.

We need much denser data sets, which is the kind of work that I do in my medical practice and it’s what I do in a research setting. The current research project is looking at the earliest biomarkers of that transition.

If we put on our systems biology hats right now, there’s this transition from health, which we’re so lousy at defining in mainstream medicine. We define health as the absence of disease. It’s a circular argument that still centers us around disease.

In fact, we want to define health using the metrics that a patient values the most. And then we want to look at these transition states, from health to pre-disease onto disease, and then how to reverse the disease or even the pre-disease.

In the case of metabolic health, we’re looking at the transition from health to pre-disease to understand the drivers. We know, for instance, that fasting glucose is a pretty late event in the spectrum of disease. We know that there are other more sensitive biomarkers that start to change way before fasting glucose, or even postprandial glucose, such as adiponectin, such as CGM dynamics, such as fasting insulin and postprandial insulin.

There was a paper in The Lancet where they followed around 6,500 civil servants in the United Kingdom for a very long time. They found that the people who made the transition to Type 2 diabetes had changes in their insulin going back 13 years.

This is flying below the radar of mainstream medicine. If we could get better at understanding some of those biomarker changes, it would allow us to intervene sooner when there’s a much greater chance of reversal, of getting people to go from that metabolically inflexible state, back to a state of metabolic flexibility.

In our research project, we’re looking at more than 100 different biomarkers. We’re doing a systematic review to compare the time course of these biomarkers. There’s a long list: ALT, one of the liver enzymes, inflammatory markers, like high sensitivity C reactive protein, the interleukins, other adipokines, leptin. We can also look at metabolomics, which is a global interrogation of all those biochemical processes that can lead to metabolic inflexibility. We can look at microRNA and the proteome.

We’re still in the early stages of our project, extracting data and understanding the quality of evidence for these biomarkers with the hope that we could come up with an improved way of diagnosing prediabetes.

Dr. Casey Means: The way we’re looking at glucose now, people might think, “Prediabetes or Type 2 diabetes is a disorder of elevated glucose.” When in fact that is such a downstream effect of other things happening physiologically.

The way we’ve approached it diagnostically has created a misperception in our minds, when in fact it’s a very complex disruption of many different pathways that can ultimately result in elevated glucose levels. In your research so far, do you have a sense that there are different types of progression towards metabolic dysfunction with different sets of biomarkers, or that there is one core progression towards diabetes?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: That’s really one of the central research questions that we have, because we know if you look at Type 2 diabetes, that there are multiple subphenotypes. There are three subphenotypes published by Joel Dudley in an analysis that he did at Mount Sinai. I’ve heard some talks by Jessica Mega at Google about six different subphenotypes for Type 2 diabetes. I’m especially interested in how we figure out those people who are most amenable to diet, lifestyle, nutritional redesign, as a way of reversing their metabolic dysfunction?

You mentioned the complexity of this system. I wish there was a yes or no answer on metabolic flexibility or prediabetes. Turns out it’s more of a spectrum. As we understand these drivers and signaling pathways, it’s going to help us unravel some of that complexity so that we better understand what we can do about it. And hopefully that’ll help with the buy-in of our conventional medicine colleagues.

On the role of genetics in metabolic dysfunction and what you can do about it …

Dr. Casey Means: One thing we haven’t really touched on is the genetic component. A lot of people say things like, “Oh, diabetes runs in my family.” The implication is that there’s an inevitability to it. And yet a lot of research suggests that more than 70% of Type 2 diabetes is probably preventable. Thinking back on medical school, I can’t really remember a single genetic pathway I learned that was associated with diabetes.

There’s still a bit of mystery around how much of metabolic dysfunction is genetic and if it is, are there lifestyle and environmental factors that could still move those pathways in the right direction? What have you learned about the genetics of metabolism, and what that means for the average person?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: If we look first at heritability, we know that with Type 2 diabetes, it’s somewhere around 20 to 70%. The range is so wide because there’s so much complexity to this system. And what I understand from the literature on the genomic pathways of glucose and insulin is that there are so many different genetic variations involved, literally hundreds of them. Then there’s also gene-gene interactions that we need to pay attention to, transcription factors and so forth.

That being said, there’s still a lot of value to understanding genetic risk and how you adapt the environmental response to reduce the impact of that genetic risk? This gets us into epigenetics, which is yet another class of biomarkers that we’re looking at.

The genetics of Type 2 diabetes are more heritable than Type 1. A lot of people don’t realize that. If you look at twin studies, for instance, if one of the twins develops Type 2 diabetes, the risk is somewhere around 75% in the identical twin.

In terms of these genomic drivers, I wanted to look at genomics as one of the variables. So I looked at some of the different scoring systems that are available for nutrigenomics—how your genes are interacting with your food.

Yael Joffe, a dietician and also a genomicist together with one of her colleagues, Annalise Smith, came up with is a scoring system that feeds into an algorithm to look at a set of 134 SNPs [single nucleotide polymorphisms, a common form of genetic variation among people], many of which are involved in glucose and insulin. I’m using that as part of my research, starting with some of the protective single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), such as FOXO3, CAT, UCP2.

“While genes load the gun, the environment pulls the trigger. You have a lot more control and power than you might realize, and we’re still in the early stages of understanding that control and power.”

Then there’s the whole list of risk SNPs—these are pathways such as energy regulation and obesity, FTO and ADRB2, I happen to be homozygous for that one. That’s the one that makes you have lifelong problems with your weight. SNPs that influence glucose and triglyceride clearance, that includes APOA2, which is one of the SNPs involved in your insulin response to the ketogenic diet. There’s a long list there, including CETP, which is involved in cholesterol. That’s another SNP related to keto response.

There are insulin resistance SNPs, including the IRS1, PPARG and DIO2, which is also involved in thyroid metabolism. There’s liver gluconeogenesis, energy balance pathways, FOXO transcription factors, vitamin D pathways, really important for glucose metabolism, and then there’s the four basic cellular pathways. That includes oxidative stress, inflammation, detoxification, and methylation. Those are some of the cellular pathways that then map onto the insulin and glucose pathways.

Dr. Casey Means: There’s literally a gene that has an SNP that changes the way you respond to saturated fat in terms of insulin sensitivity. If that’s not a window into why we need personalized diets, I don’t know what it is.

You mentioned that you’re homozygous for a SNP that has to do with lifelong weight storage. Can you speak to how having this information, which can seem really complex, can help guide our decision making towards maybe overcoming potential risk? Is it inevitable or something that we actually have a lot of control over?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: You have a lot of control. We were so excited for The Human Genome Project to get published in 2003, we thought this would completely transform medical practice. But it turns out that while genes load the gun, the environment pulls the trigger. You have a lot more control and power than you might realize, and we’re still in the early stages of understanding that control and power.

I mentioned my lifelong struggle with weight and the gene that is related to that, ADRB2. But this gene doesn’t say to me, “Oh, Sara, forget it. Buy some fat pants and just hope for the best.” That’s not my conclusion from being homozygous for this particular SNP. My conclusion is, “Girlfriend, it’s going to take me so much longer than someone else who doesn’t have these SNPs. Keep the long view, be compassionate about the slow progress.”

So instead of dropping 20 pounds on keto over a short period of time like my husband, I’m going to lose a more modest amount of weight. It gets me into the mindset of being very patient, thinking a lot about my future self, and what I want for that woman.

I know that I need to be super consistent about the food I put on my fork, I have to be super consistent about the exercise that I get, I have to structure my day around the exercise, because I know if I wait until 5 PM, it is not going to happen. It’s those sort of lifestyle changes that are in the purview of all of us, regardless of your genetics, so that we can architect the type of lifestyle that best supports us personally.

On what we’re learning from continuous glucose monitoring …

Dr. Casey Means: One other thing I wanted to dig into is whether you’ve seen any studies that have to do with continuous glucose monitoring as it relates to prediabetes risk. We talk about metrics like glycemic variability or area under the curve after a meal, but have you seen anything consistent emerging in the research?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: From the work of Michael Snyder at Stanford, we know that getting this dense data changes our ability to diagnose metabolic dysfunction. As an example, in his small study on glucotypes, he found that if you use a continuous glucose monitor instead of relying just on that snapshot of fasting glucose and A1C, you’re going to pick up 15% more prediabetics, 2% more diabetics.

We’re also seeing that the cutoff of 140 mg/dL for two hour glucose doesn’t work. We actually need a tighter cutoff. What I see with my patients, and this is echoed in the literature, is that a mean glucose less than 100, with a standard deviation somewhere around 15, is a sign of metabolic health.

We discussed a paper that went a bit further ….

Dr. Casey Means: Right, a paper called “New Insights from Continuous Glucose Monitoring into the Root to Diabetes.” It showed that continuous glucose monitoring allows for a better Type 2 diabetes risk development categorization than fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1C. They found that percent time under 100 mg/dL in a 24-hour period was more predictive of future diabetes risk than fasting glucose. A 10% increase in the time under 100 mg/dL, resulted in a 0.69 odds ratio of developing Type 2 diabetes. Those are gigantic risk reduction numbers

Now, this was not an interventional study. There’s not a good sense of what the diets wereA lot of this is going to have to do with nutrient quality and keeping glucose under 100 through metabolic machinery that is functioning properly, not just by hacking the system. That’s a big caveat, which the paper didn’t really get into. But the really hopeful message is that dense data could pick up a lot more early diagnosis and help us figure out how to optimize what we’re shooting for to reduce our risk.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: That 31% reduction is substantial. And that’s with the most basic of analytics. Just imagine how much more data we can get the deeper that we look at this picture.

On how to develop your own sense of interoception …

Dr. Casey Means: Circling back to our earlier discussion about interoception, something that’s lost on us in modern living because of how we’re just always running, always stimulated. I’d love to hear your thoughts on how people can maybe take a step towards improving interoception in their own daily busy lives and what that could potentially unlock for them in terms of tuning in to their bodies, but also potentially having better health outcomes in the long term.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: I can tell you what works for me. One of the things I try to do on Zoom is co-regulation, like extending my exhale, purposely slowing down my speech so that I’m speaking on the exhale, taking deep abdominal breaths to cue the patient I’m speaking to.

But, as I mentioned earlier, my interoception system broke. It just got fried in my 20s during medical training. That’s why I love wearables. My Oura tells me when I’m traveling too much. It tells me when I’m spending too much time working. I’ve gone through like 1,200 citations for this systematic review in our research. Sometimes it’s late at night because I’ve got a research meeting the next day. My Garmin tells me when I’ve overshot. Sometimes it’s easier to start with the overshooting, and to recognize the consequences of it, and then pull back and practice something different next time.

Do you have a favorite place to begin with interoception?

Dr. Casey Means: I’m really with you on wearables. I’ve got a Whoop on right now, I’ve got my CMG on. I used several other devices this morning—Lumen, Biosense, Keto Mojo.

It is an uphill battle to be in touch with our bodies, in the world that we’re living in with the demands on our attention and time. What wearables do for me is help cut through that noise and understand what’s really going on inside, and then I can reflect on how that feels. The data becomes a touch point for me to focus on the subjective component of my body.

For instance, this morning, after the fast, my ketones were higher, my glucose was lower. It gave me an opportunity to say, “How do I feel right now?” Really check in. I wrote it down, and I was feeling what you described as that ketone mind, feeling really sharp and clear, a little floaty.

The wearables become the centralizing force around diving into the subjective/objective relationship. That’s the tech version of it. The simple version of it that plays out even more in my daily life is just my heartbeat and my breath.

From more meditation practice, I consider my breath. I breathe into my heart, feel my heartbeat for a few moments. On a Zoom, I’ll often take a moment after I finish talking to do that and reset, and I crave it now. I crave the moment that I can do that.

On Dr. Gottfried’s morning routine …

Dr. Casey Means: I was inspired by a recent post you did about your morning routine and how you really intentionally take the time to start the day with some of this meditative work to get into that interoception mindset early on. I’m sure people would love hearing about that.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: I’ve had a morning routine for many years. It’s the key to career longevity, to avoiding burnout—which, as you know, we have very high rates of both burnout and suicide in healthcare.

I get up around 6 am. I used to have a cup of matcha and then I discovered that I can’t tolerate any caffeine right now. So I make electrolytes. I either make it myself with lemon and salt, or I use something that’s packaged, designed for metabolic flexibility. I drink about 24 ounces of electrolytes.

Then I breathe. I go outside in early morning light. I do Buteyko breathing right now because it helps me with respiratory efficiency. I have a voice disorder from public speaking for so many years and not breathing correctly. So Buteyko breathing is a form of breathing that’s highly efficient. It’s designed for people with asthma. It also helps those of us with voice disorders, and even elite athletes. My voice therapist taught me.

I do Buteyko for about 20 minutes. Sometimes I’ll read something sacred, because I think that’s a potent way to start the day. My current sacred text is Byron Katie.

Then I hop on that Peloton and get my first workout in. I’m obsessed with Power Zone training and lifting heavy weights.

Dr. Casey Means: You got me into Power Zones and I am so grateful.

Thank you for the work you do, and thank you for coming on today. How can people find you and follow you?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: The way that people can learn more about me is to go to saragottfriedmd.com. That’s the mothership, the website where most of the action is happening. You can submit your receipt for the new book and get bonus content that can take you further with the protocol.I spend a lot of time on Instagram. That’s the social media platform I consider a lab. I’m constantly experimenting and testing things there, infographics and other ideas. And then, if folks want to learn more about Thomas Jefferson University and the work in Precision Medicine, you can go to Marcus Institute of Integrative Health. Thank you, Casey, for a lovely and broad conversation!