For years, fat was dietary enemy number one. It was blamed for weight gain, chronic diseases, and other illnesses. Although science disproved this link, many misconceptions still linger.

The reality is that healthy fats—including certain cooking oils—can deliver powerful benefits for metabolic health, such as lowering inflammation and improving insulin sensitivity, especially when they are replacing carbs or less healthy fats. Your body also needs fat to absorb key vitamins like A, D, E, and K. The trick is choosing the right fats.

How Does Dietary Fat Affect Metabolic Health?

Fat is an essential nutrient. Your body needs dietary fat to protect organs, support cell function, make hormones, and provide energy. Fat also may help you feel full and more satisfied because it takes longer to digest than other nutrients. So although it sounds counterintuitive, swapping in a little fat for other components in your meals and snacks may help you lose weight or maintain a healthy weight.

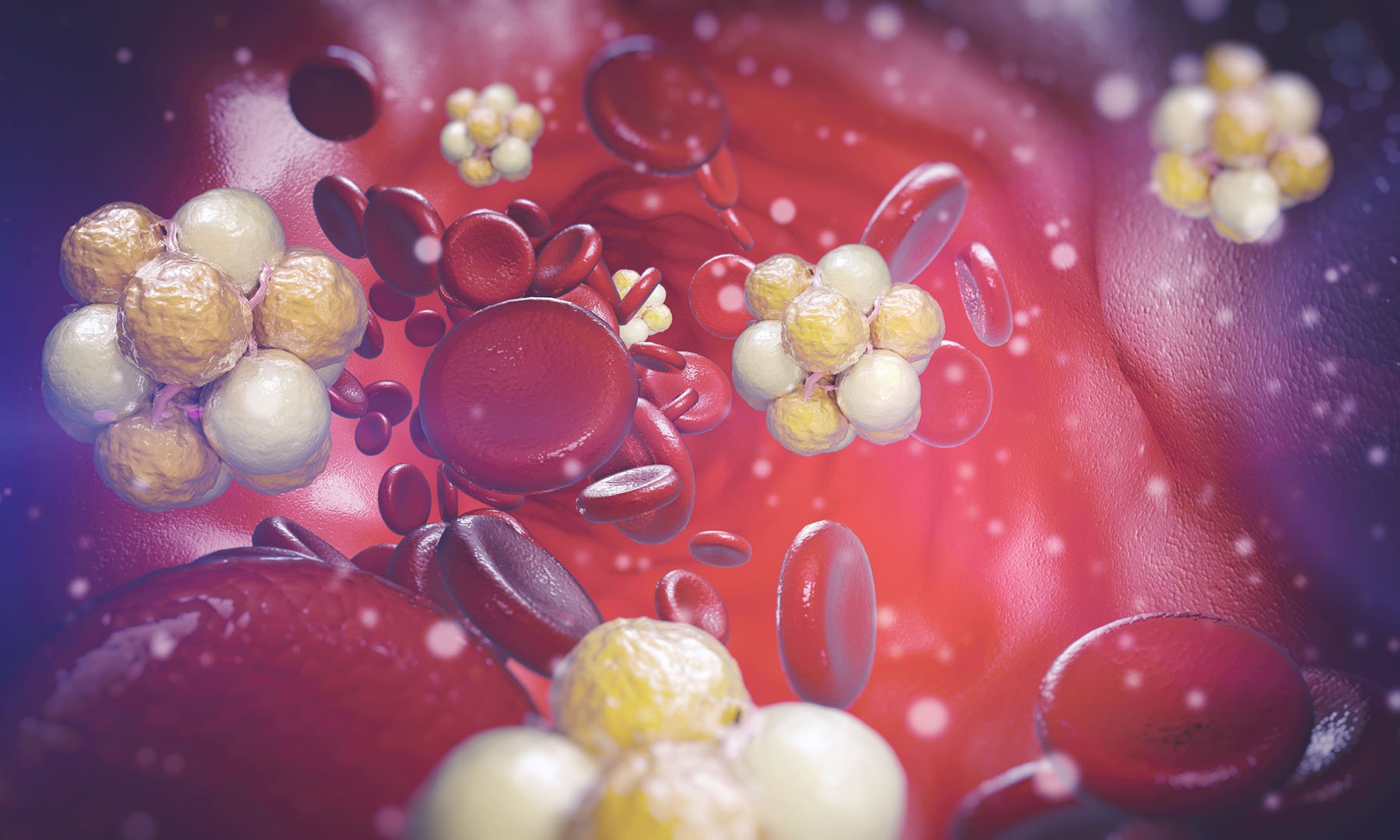

Whether fat helps or harms your metabolic health depends on the kinds of fat you consume and how you use them. The slow digestion means that fat can inhibit your body’s glycemic response and blunt spikes in blood sugar. However, the wrong kinds of fat (such as trans fats) can trigger changes in your cells that lead to inflammation.

How can you sort the good fat from the bad? First, let’s look at the chemistry involved: Most dietary fats are made from a carbon backbone attached to three fatty acids of varying lengths. Short-chain fatty acids have fewer than 6 carbon atoms; medium-chain ones have 6 to 12; and long-chain fatty acids have 13 to 21. How they’re put together separates them into different groups and determines how each fat affects your body. Here’s a primer on the main kinds of fat:

1. Trans fats

Most trans fats are made through a process that adds hydrogen to vegetable oil, which turns it solid at room temperature. These partially hydrogenated oils are cheap to make and don’t spoil as quickly as other fats, so they were often used in processed foods that require extended shelf life. But studies reveal that eating a diet high in trans fats raises LDL cholesterol, lowers HDL levels, and leads to increased risk of heart disease. Trans fat consumption also triggers inflammation and may impair your insulin response, setting the stage for metabolic issues such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

In 2015, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration banned food manufacturers from adding artificial trans fats to products. Trans fats also occur naturally in small amounts in dairy and meat products, but scientific reviews show that these fats don’t have the same harmful effect as their more abundant manmade counterparts.

2. Saturated fats

Saturated fats are found in animal products (such as meat and dairy) and tropical oils like coconut and palm oils. Their carbon atoms are saturated with hydrogen molecules and tightly packed together, so they’re usually solid at room temperature.

For decades, experts blamed saturated fat for heart attacks and strokes: It drives up LDL cholesterol in some people, the kind that can build up in the walls of your blood vessels. This can narrow or block blood flow, resulting in heart disease. But more recently, studies have poked holes in this theory. One review of nearly 350,000 people concluded that saturated fat isn’t linked with heart disease or heart attack, while another analysis of 15 studies showed that cutting back on saturated fat doesn’t reduce the risk of strokes and non-fatal heart attacks. (It’s useful to note that the review found there was a decline in cardiovascular events in studies that replaced saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats; no decline was seen in studies that replaced saturated fat with carbohydrates or protein.) Additionally, this clinical study revealed that a high-fat version of the well-known DASH diet had similar effects on lowering blood pressure as the low-fat counterpart, but had some beneficial changes in blood lipids—specifically, triglycerides and VLDL concentrations.

The problem, scientists say, is that fat is one part of the whole package of nutrients in food. For example, the saturated fats in dairy products are served up with a dose of heart-healthy minerals, such as calcium and magnesium, while the fats in bacon and hot dogs come with a side of artificial preservatives. There are also different kinds of saturated fat, which have different effects on the body. As one review put it, “The overall evidence in the literature suggests that medium-chain saturated fats (such as lauric acid, found in coconut oil) and monounsaturated fat (oleic acid, found in olive oil) are less likely to promote insulin resistance, inflammation, and fat storage compared to long-chain saturated fatty acids (such as stearic acid found in large quantities in butter, but particularly palmitic acid found in palm oil) especially when consumed on top of a diet moderate in refined carbohydrates.” In addition, your body also produces metabolically unhealthy fats as one result of excessive carbohydrate intake, so the amount of inflammatory fat in your bloodstream may not be entirely dependent on the amount of saturated fat you consume.

What’s more, cutting back on saturated fat can mean that you’re replacing those calories with something else. That something matters: Harvard researchers looked back at the dietary history of thousands of participants over more than 20 years. They looked for associations between dietary patterns and heart disease risk. They found that in those who replaced a portion of the saturated fats in their diet with something else, replacing it with healthier forms of unsaturated fats or whole grains was beneficial in terms of heart disease risk while replacing it with sugar or refined carbohydrates was not helpful.

Whether this means you can slather butter on everything is still up for debate. The American Heart Association recommends keeping saturated fats to 5 to 6 percent of your calories and trading them for healthier unsaturated fats. Meanwhile, others argue that the amount or kinds of fat you eat isn’t tied to heart attacks or heart disease-related deaths. Fat may also help you feel full and satisfied, which can encourage weight loss. But many experts do agree that focusing on the bigger dietary picture—and eating a diet full of whole foods and low in processed foods—is key.

3. Unsaturated fats

While saturated fats are tightly stacked in a straight line, unsaturated fats have bends or kinks that don’t allow for as many hydrogen atoms. They’re more loosely packed and fluid, so they’re usually liquid at room temperature.

The 2020 U.S. Dietary Guidelines recommend keeping saturated fats to 10 percent of calories, and replacing them with unsaturated fats when possible, such as those found in fish, nuts, and vegetable oils. But you still need to pay attention to these fats and the way they’re processed. Certain kinds, such as highly processed vegetable and seed oils, can do more harm than good.

There are two kinds of unsaturated fats. They’re grouped by how many double bonds they have in their carbon chains: monounsaturated (one) or polyunsaturated (more than one) fats. Some polyunsaturated fats are “essential fatty acids,” meaning they cannot be produced by our bodies and can only be taken in through our diet.

Monounsaturated fats: Olive oil, avocados, and nuts and seeds are all high in monounsaturated fats. They’re also found in animal products such as chicken and beef. Research shows that higher intake of monounsaturated fats from olive oil may be associated with lower risks of heart disease. These fats can also help reduce hunger and improve satiety, which may spur weight loss. According to a study in Diabetes Care, people with Type 2 diabetes who eat a diet high in monounsaturated fats shed more weight and experienced greater reductions in blood glucose levels compared to those who follow a diet higher in carbs.

Polyunsaturated fats: Your body needs polyunsaturated fatty acids for brain function. There are two main kinds of polyunsaturated fats: omega-3s and omega-6s. The first are found in fatty fish (such as salmon and mackerel), walnuts, and flax seeds. These fats have a powerful anti-inflammatory effect. That’s because, in part, they make up part of the cell membrane, which affects how that cell functions. They’re also used to make hormones that regulate inflammation, blood clotting, and more. Studies show that omega-3s may protect against heart disease, certain cancers, dementia, and more.

Omega-6s are found in many vegetable and seed oils, such as corn, soybean, safflower, and sunflower oils. These fats are often added to processed and fried foods, which means many Americans consume far more omega-6s than omega-3s. What effect this has is a subject of debate. Some experts suggest that getting too many omega-6s can drive inflammation in the body, and other research posits that a higher ratio of omega-6s to omega-3s may also raise the risk of obesity.

A potential mechanism may be that polyunsaturated fats are more susceptible to a process called lipid peroxidation. That’s when oxidants attack them, creating compounds called peroxides in the body. One polyunsaturated fat called linoleic acid (LA) makes byproducts that may be particularly dangerous to metabolic health. One hypothesis is that the buildup of LA peroxides may change the growth of fat cells in a way where they become more insulin resistant; another is that oxidized LDL might promote inflammation.

But not everyone agrees that the amount of omega-6s, including linoleic acid, being consumed by most people is particularly harmful. For example, a science advisory from the American Heart Association found that even though they can be converted to inflammatory molecules, only about 0.2% of them actually are converted (“little direct evidence supports a net proinflammatory, proatherogenic effect of LA in humans”). In studies on both sides, researchers add that more study is needed.

Another problem with many of these vegetable and seed oils is that they’re processed. They’re often chemically extracted and heated to high temperatures, which may deplete many of their nutrients as well as result in toxic byproducts.

Which Fats and Oils Should You Be Cooking With?

So how does this all translate to the cooking oils and fats available at the supermarket? Below is what to reach for and how best to use it.

1. Olive oil

A staple of the healthy Mediterranean diet, extra-virgin olive oil is high in monounsaturated fats (74 percent of fats), vitamins E and K, and polyphenol antioxidants, which protect against inflammation. It’s also a source of saturated fat (16 percent) and a mix of omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fats (10 percent). This package of nutrients may deliver its metabolic health benefits.

According to a study of nearly 93,000 people, those who averaged at least half a tablespoon of olive oil daily had an 18 percent lower chance of developing heart disease compared to those who ate less olive oil. Another analysis of 33 studies found that those who consumed the most olive oil had a reduced risk of Type 2 diabetes compared to those who ate the least.

When buying olive oil, look for “extra virgin” on the label. Other kinds are often processed and heated to high temperatures, which means they don’t have the same health benefits.

Extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO) is best for low-temperature cooking or whipping up dressings and vinaigrettes [SL1] because it has a low smoke point, or the temperature at which it starts to burn and break down.

2. Avocado oil

Pressed from avocado fruit, avocado oil has a similar nutrient breakdown to olive oil. It’s high in monounsaturated fat (71 percent), most of which comes from an omega-9 fat called oleic acid. The rest is made up of saturated (12 percent) and polyunsaturated fat (14 percent).

In one small study, 13 overweight adults in their 60s ate either avocado oil or butter as part of a high-fat breakfast. Those who had avocado oil had better insulin and glucose levels after the meal. The researchers explain that avocado oil may help the body better manage inflammation.

A perk of avocado oil is that it has a high smoke point of more than 480 degrees F. You can use it for frying, roasting, and more.

3. Coconut oil

This oil is about 80 percent saturated fat. About two-thirds of that is made up of MCTs, or medium-chain triglycerides. These fats have shorter carbon chains than the LCTs (long-chain triglycerides) found in olive oil and avocados, which means they’re processed by our bodies differently. Unlike other fats, MCTs may be less reliant on being broken down with the help of pancreatic enzymes. They’re metabolized in the liver and hit the bloodstream faster. Some research suggests that they’re more likely to be burned for energy than stored as fat, which is why they’re linked with benefits such as weight loss, increased energy, and a more optimal lipid profile.

And that’s why coconut oil is often touted as healthy. But the science is mixed: while one small study suggested that coconut oil improves insulin sensitivity compared to peanut oil, some advisory groups like the American Heart Association still advise against excessive consumption of coconut oil. More research is needed on long-term effects. The takeaway? Coconut oil probably won’t do miracles for your wellbeing, but it also doesn’t guarantee heart disease or diabetes, Lustig says. With a smoke point of more than 350 degrees F, unrefined coconut oil works best for stir- and pan-frying.

4. Butter and ghee

Butter contains more than 400 different kinds of fatty acids, with most of them (63 percent) as saturated fat. It also delivers vitamin A and a type of fat called butyric acid. A review involving more than 635,000 people found that eating butter didn’t raise the risk for developing heart disease and, in fact, slightly lowered the odds of having Type 2 diabetes. But other research suggests that choosing olive or coconut oil may be a better move: Compared to butter, olive oil reduces LDL cholesterol while coconut oil raises HDL levels.

Butter has a smoke point of around 350 degrees F, so it’s good for lower-temperature cooking, such as sauteing. Ghee or clarified butter (butter with the water and milk solids removed) has a higher one, of around 480 degrees F, making it a better option for frying. Studies haven’t demonstrated a significant nutritional difference between ghee and butter.

5. MCT oil

This oil is made by extracting the MCTs from coconut or palm kernel oil, a process called fractionation.

A few small, short-term studies suggest that this oil may help lead to weight loss. In one, people who consumed roughly 5 teaspoons of MCT oil as part of a 1,500- to 1,800-calorie diet daily shed 3.5 more pounds after four months than those who had the same amount of olive oil. Another six-week study found that 22 people who swapped MCT oil for some of their usual fat boosted their insulin sensitivity by 12 percent, as shown through intravenous glucose tolerance tests.

While the science is encouraging, more long-term research is needed. Because the smoke point of MCT oil is low (around 320 degrees F), it’s not recommended for cooking. You can add it to foods, such as cooked oatmeal or salad dressing, or stir into coffee or smoothies.

6. Rendered fats

These animal fats, including tallow (beef or mutton), lard (pork), and poultry fat (chicken schmaltz and duck fat), are drawn out of meats through a slow cooking process. The fat melts away from the meat. Rendered fats tend to be higher in saturated fat (anywhere from roughly 30 to 50 percent saturated fat), although they’re still in lower amounts than butter.

Some research suggests that the saturated fat from meat products may be more harmful to the heart than the types found in dairy. But, they are still a better option than some of their hydrogenated counterparts, such as shortening.

Each fat has its own unique flavor and nutrient profile:

- Tallow is high in choline (an essential nutrient needed to form cell membranes and regulate muscle control, mood, and memory) and vitamins D and E. Because of its high smoke point (about 400 degrees F) and beefy flavor, it’s often used for deep-frying.

- Lard also contains choline and vitamins D. It has a mild pork flavor and high smoke point (about 370 degrees F), so it works for most types of cooking. It adds flakiness to baked goods.

- Poultry fat is lower in saturated fat and higher in unsaturated fatty acids than lard and tallow. They also have a higher smoke point (about 375 degrees F).

You can buy rendered fats ready-made, such as those by EPIC, or make your own.