Dietary guidelines attempt a seemingly impossible task. They set a generalized recommendation for something so personal: nutrition. When it comes to food, we have a range of tastes, accessibility, affordability, cultural traditions, ethical considerations, and even allergies or intolerances. Plus, we have different macro- and micronutrient needs based on our health and metabolism. Yet, guidelines provide a necessary public consensus on what makes up a relatively healthful diet. But how do dietary guidelines come about, how accurate are they, and how closely should we adhere to them when fueling our bodies?

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans is “intended to synthesize the latest nutrition science into simple guidelines that then form the foundation of all government food programs and are followed by almost all health care institutions and public health and professional societies . . .” writes Levels Advisor Mark Hyman, MD, in Food Fix: How to Save Our Health, Our Economy, Our Communities, and Our Planet—One Bite at a Time.

What are dietary guidelines?

Every five years since 1980, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have jointly released the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). Since 1985, the two governmental departments have assembled an outside advisory committee to review scientific data on health and nutrition and prepare a report that informs the government on what to include in the revised guidelines.

Some health associations also make diet and lifestyle recommendations based on scientific data. For example, the American Heart Association (ADA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) have a joint Recommended Dietary Pattern. And the American Diabetes Association (ADA) has a Nutrition Consensus Report. Medical professionals often use these tools, along with the DGA, to make recommendations for their patients. But the general public can also access summaries of heart-healthy or diabetes-friendly nutritional advice on respective agency websites. The federal scientific consensus remains the DGA, however.

The DGA’s nutrition standards are disseminated through federal agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), USDA, HHS, and more. These agencies then provide federal funding for research and public health programs that help implement the nutritional standards or educate about them. The DGA helps inform public school lunch programs; Child and Adult Care Food Programs (CACFP); Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), the latter of which serves about half of all infants born in the nation.

“‘It turns out that the USDA didn’t invent the food pyramid, Sweden did. Sweden’s was scrapped, but the USDA adopted it anyway, because its 1980s policies of agricultural monoculture had generated a glut of cheap refined carbohydrate, which served as the base of the pyramid.”’

Ultimately the DGA is intended to serve as a roadmap on what foods and beverages boost health and prevent disease while meeting nutrient needs. But has it had an impact over the years? According to the 2020–2025 DGA release, Americans now have a total Healthy Eating Index (HEI) of 56 out of 100. The USDA created the score to indicate how well Americans are following the DGA. The score is down 3 points from where it was in 2015 and 2010.

What has changed? When comparing dietary intakes from the early aughts to those just five years ago, people are not consuming more fruits and vegetables, shows an analysis by the American Public Health Association (APHA). But they are swapping refined grains for whole grains. And they’re eating less added sugar and less saturated fat. The fat topic is a source of contention among experts and illustrates a pitfall of the DGA.

Despite four decades of DGA releases, the prevalence of obesity in the U.S. continues to grow, according to the CDC. The APHA analysis acknowledges a DGA challenge: Nutrition research, like all science, is iterative. And the DGA, updated every five years, is intentionally careful about incorporating new research. That makes sense but can also be a limitation, especially when the first guidelines got it wrong for various reasons, and we still see the ramifications of that. For years, the DGA vilified fat and championed carbs. Something Hyman calls “a deadly idea.”

How did carbs become the base of the pyramid?

The USDA debuted America’s first Food Guide Pyramid in 1992 as a familiar tool to educate Americans about the nutrition recommendations that had prevailed for more than a decade in the DGA. But there’s more to the story.

“It turns out that the USDA didn’t invent the food pyramid, Sweden did,” writes Levels Advisor Robert Lustig, MD in Metabolical: The Lure and the Lies of Processed Food, Nutrition, and Modern Medicine. “Sweden’s was scrapped, but the USDA adopted it anyway, because its 1980s policies of agricultural monoculture had generated a glut of cheap refined carbohydrate, which served as the base of the pyramid.”

Indeed, bread, cereal, rice, and pasta made up that original pyramid’s base. Next came a section for fruits and veggies, followed by dairy, eggs, meat, beans, and nuts. The pyramid tip featured fats, oils, and sugars—all to be used sparingly.

But that wasn’t the original intent. “USDA nutritionists had initially settled on 5 to 9 servings of fresh fruits and vegetables and 3 to 4 servings of whole grains per day, putting refined carbohydrate (like crackers) at the top,” Lustig explains. Yet when the pyramid was revealed, 6 to 11 of all types of carbs, including crackers, had found their way to the base.

“The Food Pyramid . . . was never based on science,” writes Lustig in Fat Chance: Beating the Odds Against Sugar, Processed Food, Obesity, and Disease.

What happened? Conflicts of interest. “One of the originators of the Food Pyramid, Luise Light,” writes Lustig in Metabolical, “is quoted as saying: ‘Ultimately the food industry dictates the government’s food advice, shaping the nutrition agenda delivered to the public. In fact, to the food industry, the purpose of food guides is to persuade consumers that all foods (especially those that they’re selling) fit into a healthful diet.’”

And these conflicts of interest were at play well before the Food Pyramid came on the scene. Before the USDA and HHS released the first DGA in 1980, we had the Dietary Goals for the United States. The U.S. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, led by Senator George McGovern, released the publication in 1977.

According to Lustig, McGovern commissioned a labor reporter, Nick Mottern, who had zero scientific background, to write the goals. And Mottern did so based on the work and opinions of Harvard nutritionist Mark Hegsted. Yet other researchers were not in agreement with Hegsted’s recommendation that Americans limit fat intake.

Sure, fat was possibly correlating with heart disease. But researchers hadn’t yet dissected that the big bad wolf of the fats is trans-fat. Trans-fat use surged in the 1960s, Lustig says. Meanwhile, in the mid-1960s, sugar consumption had also seriously raised the eyebrow of British physiologist and researcher John Yudkin, who published his extensive research on the topic in several papers, but also in his 1972 book Pure, White and Deadly.

But Hegsted authored a 1967 paper in the New England Journal of Medicine that, according to Hyman, “blamed fat and gave sugar a pass for heart disease.” And Hyman writes, “Turns out the sugar lobby paid him [and a coauthor] the equivalent of [nearly] $50,000 in today’s dollars to write that article giving sugar a pass, even though studies showed that inflammation, abnormal cholesterol, and other heart disease biomarkers were driven by sugar and starch.”

Therefore, fat—not sugar—became America’s demon of the late twentieth century. And those original Dietary Goals encouraged Americans to reduce their fat consumption and ramp up their complex carbs.

“But when you take the fat out, the food tastes like cardboard,” writes Lustig in Fat Chance. “And palatability equals sales. The food industry had to find ways to make this low-fat fare palatable. They, therefore, upped the carbohydrate content, specifically the sugar.”

Enter the new millennium, and the low-carb diet concept was beginning to take hold, thanks to new research and early champions like Dr. Robert Atkins, with his famous Atkins Diet. According to Lustig, several things became clearer through targeted studies: Cutting carbs improves glucose control and works for weight loss. Curbing carbs in favor of fat consumption proves beneficial for markers of heart disease. And restricting carbs improves aspects of metabolic syndrome.

Revised in 2005, the Food Guide Pyramid became MyPyramid. It no longer showed food groups in a problematic hierarchy. But it still prioritized carbs, albeit this time with the emphasis on whole grains. And it still gave saturated fats a bad name and encouraged low-fat or fat-free consumption. Eventually, the peaked icon was retired in 2011 to become MyPlate, which portions out food groups and is still used today and revised accordingly based on DGA updates.

But MyPlate still endorsed the low-fat myth, Lustig writes in Metabolical. “To its credit, at least MyPlate didn’t tout refined carbohydrates; however, its low-fat imperative continues to miss the point…” he says.

And by the time MyPlate came into effect, more than 30 years of guidelines promoting carbs as king and fats as faulty may have contributed to a growing epidemic of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

In 2015, the DGA revised its guidelines around fats: “Limit saturated fats to less than 10% of total calories daily by replacing them with unsaturated fats and limit trans fats to as low as possible.” This appeared to be an acknowledgment “after decades of overwhelming evidence that fat was not the enemy … and eating fat didn’t cause weight gain or heart disease,” Hyman writes.

How the guidelines affect government programs

Not everyone benefits from the eventual adoption of new research right away. So outdated concepts can wreak havoc on whole populations for years.

Consider that, until the 2021 changes, the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP) has been based on that retired 2005 DGA content and the corresponding MyPyramid info. Add in the fact that TFP, which includes SNAP benefits, has been notoriously based on an outdated model from the 1970s. In 2019 they averaged $1.40 per person per meal, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. To stay within that cost constraint, the TFP features a narrow range of foods, limiting people who have few resources. The TFP, the CBPP analysis says, “generates unrealistic market baskets that fail to meet some key nutrition and dietary recommendations.”

A 2017 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that people participating in SNAP have higher total and cardiovascular disease mortality compared to people who are not eligible for the program and those who are eligible but don’t participate.

But it’s not just SNAP beneficiaries who are at risk for poor nutrition based on outdated recommendations. The millions of children who eat school lunch may also pay the price and likely will for years to come. Why? For one thing, today’s guidelines, according to experts, still fail to tackle the damaging effects of added sugar.

“The USDA’s sugar recommendation mirrors its 2020 guidance on school lunches, which increased flexibility for serving processed foods and sugar to children, and decreased requirements for whole fruits and vegetables in schools,” writes Levels Co-Founder and Chief Medical Officer Casey Means, MD, in an op-ed for The Hill.

What do today’s guidelines still get wrong?

Since 2015, the DGA changed tack from its previous focus on the relationship between health outcomes and specific foods, nutrients, or basic food groups. Instead, it now focuses on the development of a healthy dietary pattern.

The DGA defines a dietary pattern as a combination of food and drink a person consumes over a day, week, or year. The DGA suggests that one’s dietary pattern may better predict overall health status and disease risk than, say, the contents of one food item or one meal. The DGA offers some dietary patterns that meet the mark. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, the Healthy U.S.-Style Dietary Pattern, the Healthy Mediterranean-Style Dietary Pattern, and the Healthy Vegetarian Dietary Pattern are all recommended.

Ultimately, healthy dietary patterns stay within calorie limits while focusing on nutrient-dense food and drink across all food groups. And they limit alcohol and items higher in sugar, saturated fat, and sodium. But the DGA also suggests people “customize… to reflect personal preferences, cultural traditions, and budgetary considerations.”

Also, in a new move, the latest DGA categorizes content by lifespan—including for infants and toddlers, children and adolescents, adults, people who are pregnant and lactating, and older adults. The intent is for people to develop healthy dietary patterns and carry them forward throughout all life stages.

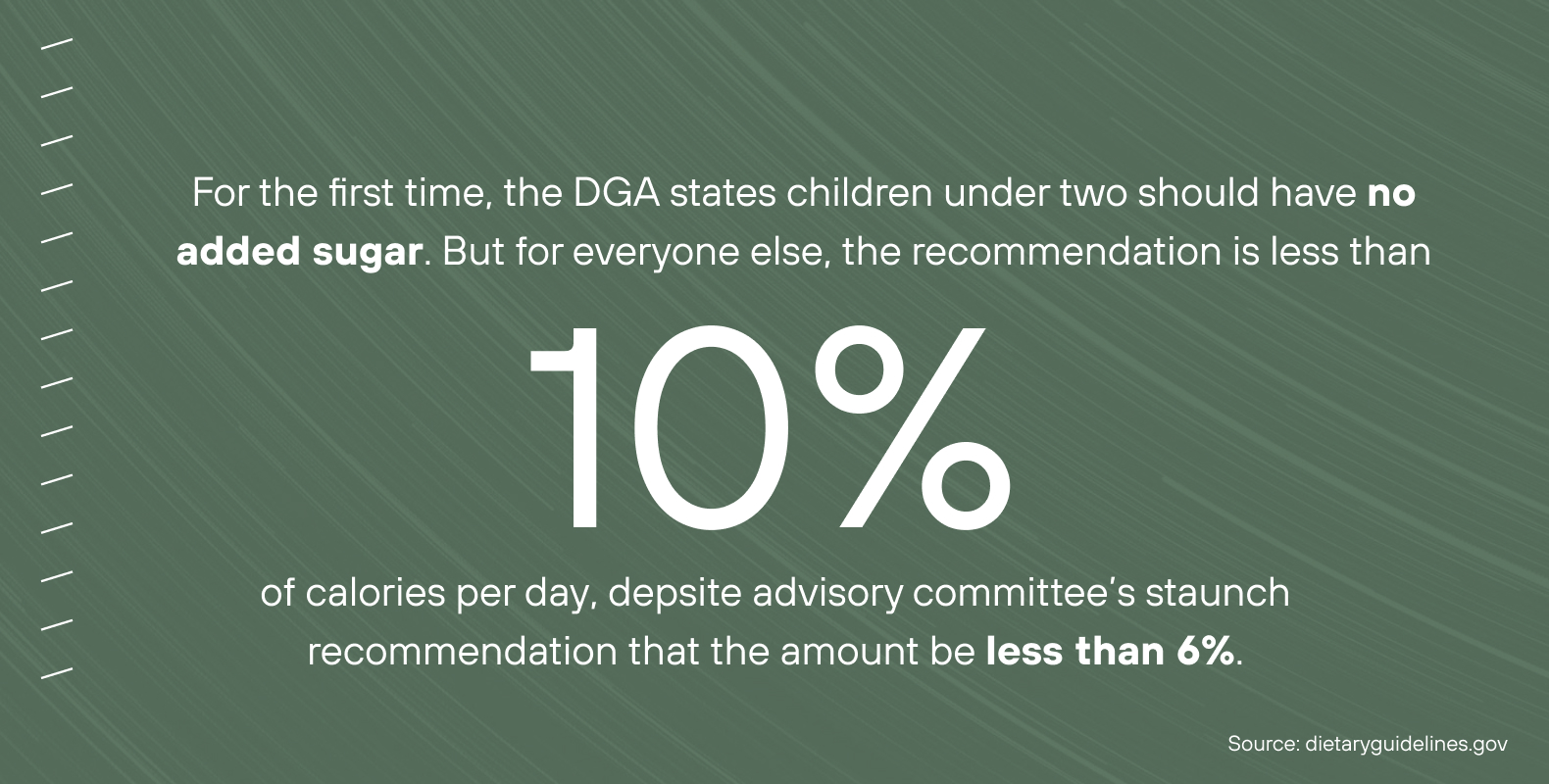

Although the newest DGA makes some positive progress, several crucial issues remain at stake. For one, the DGA’s recommendation for added sugar is too high, according to its own advisory committee. For the first time, the DGA states children under two should have no added sugar—a good move. But for everyone else, the recommendation is less than 10 percent of calories per day. When creating the revised DGA, the USDA and HHS ignored the advisory committee’s staunch recommendation that the amount be less than 6 percent. This is at a time when rates of prediabetes and obesity continue to soar.

“This is also a social justice issue,” writes Means in an op-ed for Medpage Today. “Minorities and the poor disproportionately suffer from blood sugar-related diseases and are most reliant on school lunches and nutrition assistance programs like SNAP, which are influenced by USDA guidelines. Lax USDA nutritional guidelines will lead to more sugar on the plates and in the cups of the exact people who need the most health support and will widen health and economic disparities even more.”

As a response as to why the USDA and HHS omitted this recommendation, the departments issued this statement: “The Committee’s systematic reviews supported low intakes of added sugars, but the conclusion statements did not specify an amount of added sugars that was associated with health promotion or disease prevention. The conclusions were consistent with those of the 2015 Committee.”

In 2016, Congress mandated the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to review the DGA development process. The National Academies found bias and conflicts of interest among the advisory committee. Specifically, more than half had ties to various food industries. But conflicts of interest may also lie within the USDA or HHS, the agencies that put out the finished DGA.

In one of her op-eds for The Hill, Means points out that the USDA Food and Nutrition Services openly states its conflict of interest in its mission statement: “. . . our mission is to increase food security and reduce hunger by providing children, and low-income people access to food, a healthful diet, and nutrition education in a way that supports American agriculture and inspires public confidence.”

And we can look to the USDA’s 2018 Farm Bill for additional confirmation of that agricultural support. The lack of change to added sugar mirrors the bill’s interests, “which allocated $31 billion in support of disease-promoting commodity crops,” Means explains, “(including soy, wheat, corn, and sugar, the vast majority of which are turned into disease-promoting processed foods, oils or animal feed).”

Another pitfall of the current DGA, released amidst a global pandemic in which food insecurity has been higher than usual, is that its scope to address food insecurities is limited. The DGA simply mentions the ability to customize healthy dietary patterns to accommodate budget and recommends turning to government programs like SNAP. Finally, the DGA also leaves climate change entirely out of the picture, even though food production and consumer choices impact the planet.

Should you pay attention to the guidelines at all?

The DGA itself is a 150-plus-page PDF. The newest version does feature helpful content about dietary patterns across the lifespan. But likely, you’ll find the USDA’s MyPlate website (and app), which incorporates DGA material, more accessible with its quizzes, resources, and recipes. You can view life stages in a dropdown menu and gain information about serving sizes for food groups based on the MyPlate visual.

But the DGA is just one resource when it comes to healthier eating that’s right for you. If you’re following multiple sets of guidelines, like the DGA and recommendations from the American Heart Association or American Diabetes Association, you’re going to run into inconsistencies. Remember that since it only gets a revamp every five years, the DGA may be behind on the research.

Other potential resources include your doctor or a nutritionist, especially if you’re managing a chronic disease and need further dialing in, something the DGA does not address. However, many doctors admit to minimal training in nutrition. Fortunately, there are plentiful resources available that focus on health conditions and nutrition and dive deep into the synthesis of the research literature. For starters, check out Levels Advisor-authored books, such as The Hormone Reset Diet and Women, Food and Hormones, both by Sara Gottfried, MD; The Grain Brain Whole Life Plan by David Perlmutter, MD; The Blood Sugar Solution by Mark Hyman, MD; Fat Chance by Robert Lustig, MD, Lifespan by David Sinclair, PhD, and The Wahls Protocol by Terry Wahls, MD.

Finally, so many factors play a role in what goes on your plate at any given time. Any set of guidelines cannot be one size fits all. And although it allows for customization, the DGA still falls short when considering many individualized factors. So how should you proceed?

“Your diet should be aspirational, not perfect,” Hyman writes in Food Fix. “It should contribute to better health for you, a better world for humans, including food workers and farmworkers, and a better world for the environment, our climate, and our economy.” This is achievable by focusing on real, unprocessed foods grown in a clean, sustainable way.