Enjoying a diet that supports stable blood glucose is essential to our overall health and well-being. But the medications we take generally escape the metabolic scrutiny we apply to food. However, as certain foods can increase blood glucose levels, so can certain meds.

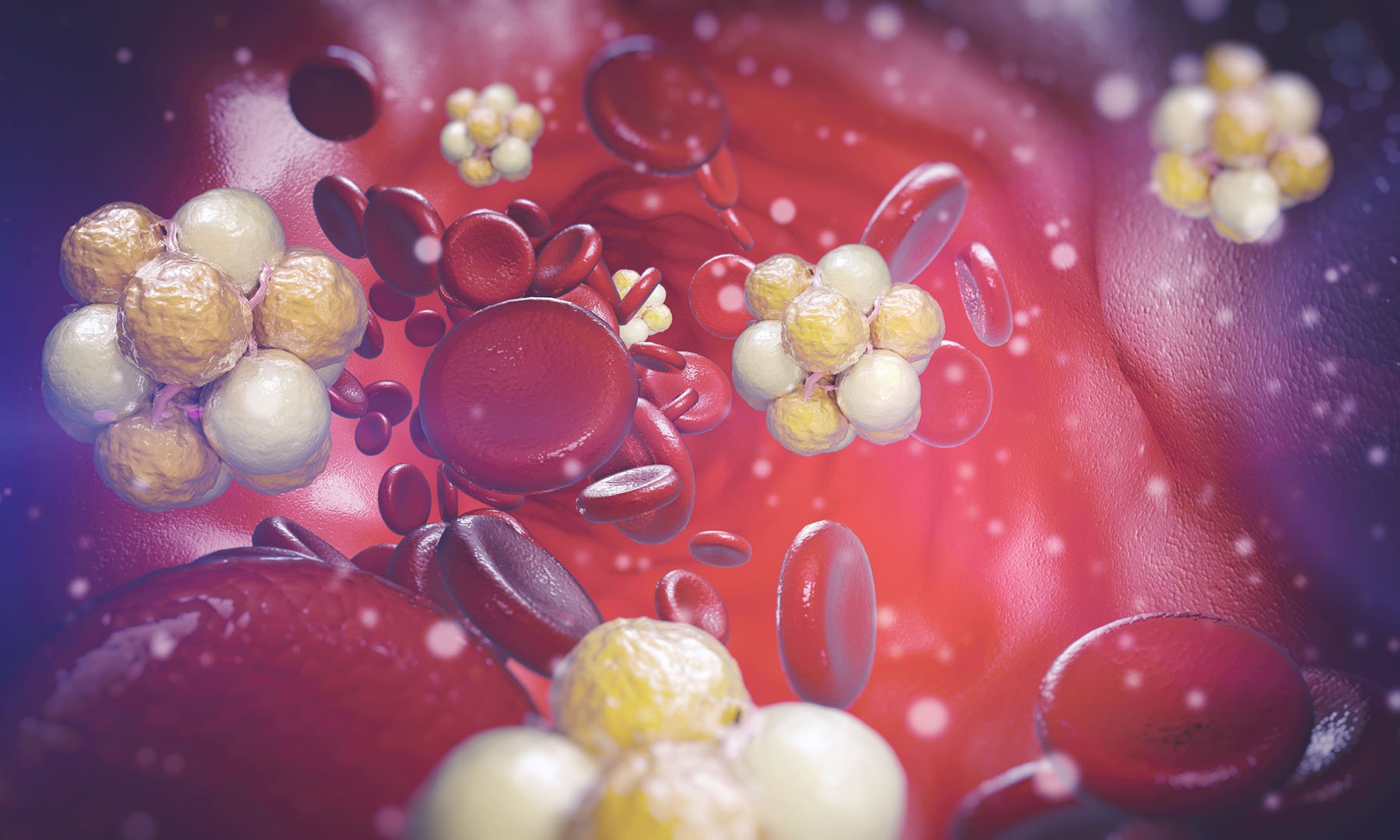

One of the primary mechanisms behind hyperglycemia, or elevated blood glucose, is insulin resistance. Insulin, a hormone produced by pancreatic beta cells, primarily helps muscle and fat cells absorb and make use of glucose, the body’s primary source of fuel, which we get mainly from food.

It is normal for blood glucose levels to rise after eating, for example. When they do, the pancreas secretes insulin, which binds to cells and helps glucose cross from the bloodstream and into those cells. Blood glucose levels subsequently decrease, restoring homeostasis.

With chronically high blood sugar—from a diet high in sugar or certain medications—the pancreas produces more insulin. This can lead to insulin resistance, where cells have trouble recognizing the hormone. Blood glucose cannot be taken in by the cells as effectively and instead remains in the bloodstream. This is called insulin resistance, or decreased insulin sensitivity. Over time, an insulin resistant state may evolve into prediabetes and, eventually, Type 2 diabetes.

To be clear: The point is not to avoid medications—both prescribed and over-the-counter—that may raise blood sugar levels. Most medications that raise blood sugar do so to a far less degree than processed carbohydrates and sugar. Also, medication-induced hyperglycemia is typically transitory, or short-lasting. Do not stop taking any medications without speaking to your doctor. The point here is to highlight which drugs may affect blood sugar so you can be more sensitive to other lifestyle decisions while on those medications.

Related article:

The ultimate guide to metabolic health

Metabolic health can be improved by consistently making choices that keep glucose levels in a stable and healthy range.

Read the ArticleStatins

What they’re used for: Statins aid in reducing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels by inhibiting the liver’s ability to create a molecule necessary for synthesizing cholesterol.

High blood LDL levels can contribute to plaque build-up in the arteries that can interfere with blood flow to the heart and brain, increasing the risk of a heart attack or stroke.

How they may affect blood sugar: It is believed that statins increase the amount of cholesterol entering the body’s beta cells. This “cholesterol loading” interferes with the ability of a protein known as GLUT2 to transport glucose across the cell’s membrane. Statins also seem to reduce activity of the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase and levels of the antioxidant CoQ10, both of which play essential roles in insulin secretion.

The FDA released a Safety Announcement in 2012 concerning “safety label changes” for statins. The report included “increased blood sugar” among its “Adverse Event Information” while emphasizing its stance that the drug’s benefits outweighed such risks.

Related article:

Beta Blockers

What they’re used for: Beta-blockers, a class of drugs commonly prescribed to lower high blood pressure and promote cardiovascular health, work by blocking the hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline from binding to a nerve cell’s beta receptors. When adrenaline and noradrenaline cannot bind to a cell, the body’s nervous system calms the heart rate. Beta-blockers also decrease the production of a blood pressure-raising protein called renin.

How they may affect blood sugar: There is some evidence that beta-blockers reduce insulin sensitivity, perhaps by interacting with the pancreas’s nerve cells. It’s less clear if this leads to elevated glucose and evidence for increased diabetes risk is mixed.

A study in The New England Journal of Medicine looked at treatment methods for hypertension in more than 12,000 adults ages 45 to 64 without diabetes. In subjects taking beta-blockers, researchers reported a 28% increase in the risk of Type 2 diabetes. These effects can largely be mitigated by choosing a medication that targets a particular beta-receptor. Beta-1 receptors are located mainly in the heart and kidneys, while beta-2 receptors can be found in multiple organs, including the pancreas. Drugs that target beta-1 receptors seem likely not to spike blood glucose levels as much as those targeting beta-2 receptors.

Because beta-blockers calm the nervous system and slow the heart rate, they can also mask telltale symptoms of hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, such as a rapid heart rate.

Corticosteroids

What they’re used for: Corticosteroids—typically referred to just as steroids—such as prednisone reduce inflammation, the body’s natural defense mechanism, protecting tissues from the body’s immune system. Acute, or short-term, inflammation is essential for fighting viruses and other foreign bodies. But chronic, or long-term, inflammation can cause significant damage. These drugs are commonly prescribed to treat conditions including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and allergies. Steroids either suppress the release of pro-inflammatory agents (from immune cells on patrol, such as white blood cells) or induce the production of inflammation-fighting agents.

How they may affect blood sugar: Steroids impact beta-cell function, impeding insulin synthesis. They may also stimulate enzymes involved in glucose production, resulting in elevated blood glucose levels on two fronts: the liver and kidneys pump more glucose into the bloodstream, and cells cannot accept and make use of glucose as readily because of decreased insulin production and increased insulin resistance.

In one study involving 32 men with normal fasting glucose levels, post-meal blood glucose increased by as much as 27% relative to the placebo group in participants who took 30 mg of prednisolone, an oral steroid, once per day for two weeks.

Dose duration has been shown to impact the severity of these effects. Long-term use presents increased risk than short-term use, as any adverse glucose-related side effects seem to subside upon discontinuation of the drug.

Antipsychotics

What they’re used for: Antipsychotics, such as clozapine and olanzapine, help treat conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder by interacting with different cell receptors in the brain.

How they may affect blood sugar: People struggling with severe mental illness are two to three times more likely to develop Type 2 diabetes. This likely results from numerous risk factors related to genetics, lifestyle, environment, and medications. At least 37 common genes have been linked to schizophrenia and Type 2 diabetes.

Neuropeptides such as serotonin and dopamine act through specific cell receptors and, among their many roles in the body, are essential in controlling appetite. Antipsychotic medications block these receptors to quell excessive activity of these neuropeptides—which may contribute to symptoms of psychosis, including hallucinations—with a side effect of increasing appetite. This can lead to overeating, which in turn can contribute to weight gain, obesity, and insulin resistance. Antipsychotics also have sedative, energy-zapping qualities, which can result in less physical activity.

These medications also appear to affect insulin secretion and sensitivity directly, as they interfere with various cell receptors—including some dopaminergic, serotonergic, and adrenergic receptors—which help regulate when and how much insulin is released. They may also increase apoptosis, or cell death, in the body’s beta cells, resulting in decreased insulin secretion and consequent hyperglycemia.

Antibiotics

What they’re used for: Antibiotics is a class of medication that treats bacterial infections by killing bacteria or by slowing their growth and reproduction. These drugs can trigger both hypo- and hyperglycemia, although the risk of the former appears to be greater than that of the latter.

How they may affect blood sugar: The mechanisms by which antibiotics impact blood glucose levels remain unclear, and data in humans is relatively sparse. But the microbiome seems to play an important role.

One possibility is that antibiotics might promote an imbalance of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate—which help keep the gut healthy and functioning and may even protect against cancer. SCFAs seem to increase levels of a hormone called GLP-1, which helps lower blood sugar and improves insulin secretion and sensitivity. Butyrate, in particular, has also been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in beta cells.

The relationship between antibiotics and hyperglycemia is sparser still. Animal studies may provide some helpful clues. One study suggests that gatifloxacin, a common antibiotic, may reduce levels of secretory granules, which store and release insulin from pancreatic beta cells, resulting in lower insulin secretion. This, in turn, may contribute to hyperglycemia.

Decongestants

What they’re used for: Decongestants help treat allergy and cold symptoms by shrinking blood vessels in the nose and sinuses. Pseudoephedrine is the active ingredient in many decongestants.

How they may affect blood sugar: Pseudoephedrine stimulates the central nervous system to release norepinephrine, a hormone and neurotransmitter involved in the body’s fight-or-flight response. It also stimulates receptors found on nerve cells, causing muscles to contract, heart rate to increase, and blood glucose levels to rise. Glucose is our muscles’ primary source of fuel, and in a perceived life-threatening situation, the body aims to deliver it quickly so we can fend off an enemy or flee to safety. Without an actual threat, however, that surge of glucose goes unused and instead remains in the bloodstream.

Conclusion

As with most health interventions, medications that raise blood sugar—and any medication in general—require weighing the benefits and risks, and learning more can help us know which questions to ask our healthcare provider. Educating ourselves and getting curious about how supplements and medications raise blood sugar and affect our health empowers us to choose what we consume intentionally.