When you hear the word “zinc,” your mind may jump to this nutrient’s role in immune health as it’s common in lozenges and other over-the-counter cold and flu remedies. Indeed, a review of 18 trials showed that taking zinc within 24 hours of cold symptoms can significantly reduce the duration of illness. But zinc is also one of a handful of micronutrients essential for metabolic health. In fact, this mineral plays a pivotal role in your body’s insulin response.

Here, we’ll dive into the role of zinc in metabolic health and how to ensure you’re getting enough of this sometimes overlooked micronutrient.

What Is Zinc, and How Does It Affect Metabolic Health?

Zinc is an essential trace mineral, meaning it’s critical for human survival, but we need it in tiny amounts compared to macrominerals (like calcium and magnesium), which we need in much more significant amounts. As Casey Means, MD, Chief Medical Officer of Levels, explains, micronutrients are “crucial links in chain reactions that regulate every part of your body’s metabolism.” In many cases, when these micronutrients enter our body, they bind to larger protein complexes and create the “just right” molecular conditions that help proteins communicate with each other so our physiological processes can thrive, she adds.

Zinc is involved in more than 300 enzymatic functions in the human body, many of which involve cellular metabolism. For example, zinc is required to activate hundreds of different enzymes, including those that regulate thyroid hormone production and protein metabolism. It’s also necessary for fundamental physiological mechanisms like cell division and DNA synthesis.

When it comes to metabolic health, zinc’s primary role involves insulin response. Studies suggest an association between insufficient levels of zinc—along with other trace minerals like cobalt and selenium—and the development and progression of Type 2 diabetes. Pancreatic beta cells (the cells that release insulin) contain higher levels of zinc compared to other cells since this micronutrient is required for the correct processing, storage, secretion, and action of insulin. Research suggests a link between dysregulated zinc levels and pancreatic beta cell dysfunction and Type 2 diabetes risk; however, it’s unclear whether zinc deficiency is the cause or consequence of the dysfunction.

Zinc supplements have shown benefits for metabolic health. A 2018 meta-analysis of 36 studies found that zinc supplementation reduced fasting glucose by an average of 13 mg/dL compared to control groups in people with Type 2 diabetes and those at high risk but not yet diagnosed with diabetes.

The same study showed that zinc supplementation reduced the amount of C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation and a major factor in metabolic disease, by about 1.31 mg/L.

Other research has found that zinc also reduces the production of proteins called cytokines, especially the inflammatory sort that can contribute to diabetes and diabetic complications. A 2017 study showed that zinc might help speed the wound healing process in diabetic foot ulcers. The group that supplemented with 50 mg of zinc for 12 weeks had a significant reduction in the size of the ulcers compared to the placebo group. The treatment group also benefited from improved blood glucose, insulin sensitivity, HDL cholesterol, and levels of glutathione, one of the primary antioxidants in the body.

Zinc also acts partly as an antioxidant, and studies show that zinc supplementation reduces reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can drive cell-damaging oxidative stress. This is beneficial in diabetes because both acute and chronic high blood glucose increases the production of ROS. Finally, zinc is involved in insulin storage, playing a role in its structural stability (in fact, insulin is made up of six insulin molecules and two zinc molecules) and the activation of insulin receptors in beta cells, which is what allows insulin to do its job of regulating the body’s energy supply.

Zinc deficiency is also a risk factor for obesity. Recent research has identified the role of a specific zinc transporter (called ZIP13) in the regulation of synthesis of a particular cell type (called a beige adipocyte) involved in the storage of fat cells. The authors of that same study indicate that regulating zinc levels in the body could be a therapeutic target for obesity and metabolic syndrome.

How Much Zinc Do You Need?

According to the National Institutes of Health, the daily zinc requirements are:

- Men, age 19+: 11 milligrams (mg)

- Women, age 19+: 8 mg (11 mg if pregnant)

You can supplement with more zinc than the RDA since the RDA represents the minimum required amount of zinc, which may be lower than optimal zinc levels, mainly due to large-scale factors that put the general population at higher risk for zinc deficiency. Mark Hyman, MD, a Levels Advisor and best-selling author, recommends taking 30 mg daily for men and women.

The general guidance for the upper limit for zinc intake is 40 mg daily since excessive zinc intake can cause symptoms such as nausea, dizziness, headaches, and loss of appetite and is associated with high blood pressure, reduced immune function, and lower HDL cholesterol levels. Studies have also shown that very high doses of zinc from supplements (142 mg/day) may interfere with magnesium and copper absorption.

It’s important to remember that dosing varies based on your health, so it’s best to work with a medical professional to identify your ideal intake level.

How Do You Test Your Zinc Levels?

The only reliable way to diagnose a zinc deficiency is a blood test (considered more accurate than urine or hair tests). In mainstream medicine, a deficiency in this mineral is when serum zinc levels are less than:

- 70 mcg/dL in women

- 74 mcg/dL in men

Because zinc plays a role in so many parts of the body, a deficiency can cause issues in many tissues and organs but especially the skin, bones, and digestive, reproductive, nervous, and immune systems. The symptoms of a mild deficiency may be vague and include delayed wound healing, impaired taste, loss of appetite, hair loss, fertility issues, and increased susceptibility to infection. Severe deficiencies are also associated with recurrent infections and dermatitis.

Diagnosed deficiencies in zinc are not that common in the United States. That said, many experts—including Hyman—agree that zinc is one of the essential nutrients for biochemistry and metabolism, acting as the “oil that greases the wheels of our metabolism,” in Hyman’s words. Large-scale factors like depleted soils and factory foods, combined with higher nutrient requirements due to stress, medication use, and environmental toxins, are why he and others recommend that most people supplement with zinc even if they haven’t been diagnosed with a deficiency.

Dr. Hyman stresses the importance of zinc supplements even more for those with any risk factors for zinc deficiency, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which can lead to poor dietary intake of zinc, decreased absorption, or increased urinary excretion of zinc as a result of inflammation. Those with celiac disease are also at risk; approximately 50 percent of people with newly diagnosed celiac disease are at high risk for zinc inadequacy or deficiency, potentially due to malabsorption and mucosal inflammation. People on a plant-based diet are also at higher risk for zinc deficiency. There are multiple reasons for this, including that the foods highest in zinc are animal-based. Also, many plant-based foods contain a compound called a phytate, which can bind to zinc and severely decrease intestinal zinc absorption.

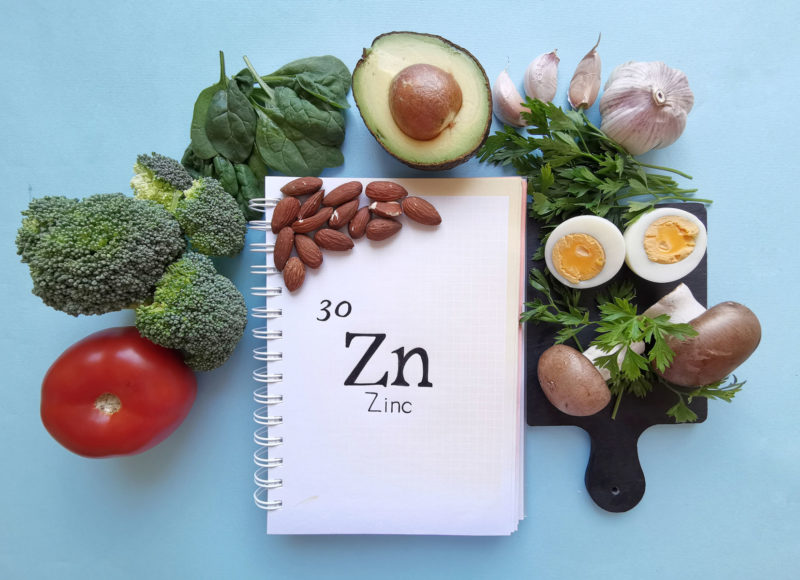

What Are the Best Foods for Zinc?

If you’re not on an exclusively plant-based diet, it’s possible to get optimal zinc intake through your diet by prioritizing foods naturally high in this mineral. Some of the top dietary sources for zinc include:

- Seafood: Eastern oysters (32 mg per 3 ounces, raw) and blue crab (3.2 mg per 3 ounces, cooked)

- Meat: Lamb (4 mg per 3 ounces), bottom sirloin (3.8 mg per 3 ounces, roasted), ground beef (5.3 mg per 3.5 ounces), and bone-in pork chops (1.9 mg per 3 ounces, roasted)

- Poultry: Turkey breast (1.5 mg per 3 ounces, roasted)

- Legumes: Lentils (1.3 mg per ½ cup, boiled) and kidney beans (0.6 mg per ½ cup canned)

- Nuts and seeds: Pumpkin seeds (2.2 mg per 1 ounce roasted) and cashews (1.5 mg per 1 ounce)

To reduce the phytate content and optimize zinc absorption from plant sources like legumes, nuts, and seeds, try grinding, soaking, germinating, malting, or fermenting these foods before you consume them.

You may see foods like fortified breakfast cereals, rice, or bread listed as top sources of zinc. However, while these foods are high in the mineral—for example, white rice contains 0.6 mg per 1 cup—they’re also refined grains, a group of foods known to promote oxidative stress and disrupt insulin sensitivity and the microbiome.

Should You Take a Zinc Supplement?

Deciding whether or not to take a zinc supplement should be a personal decision made with the help of a qualified medical professional who can help you make decisions about dosage, duration, and formulation. The mean dose of zinc given to study participants in the 2018 meta-analysis mentioned earlier was 35 mg/day but ranged from 4 to 240 mg per day (for anywhere between one and 12 months). Participants received a wide range of preparations, but zinc sulfate, gluconate, and amino chelate were the most common. No meaningful differences were observed between different dosages, duration, or zinc formulations.

If you supplement with zinc, know that it reacts with some medications. Zinc may interact with certain antibiotics, such as quinolone antibiotics (like Cipro) and tetracycline antibiotics (such as Achromycin and Sumycin). Experts recommend taking antibiotics at least two hours before or four to six hours after taking a zinc supplement to minimize this interaction. Zinc may also interfere with the action of penicillamine, a drug used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. You should take zinc supplements at least two hours before or after taking penicillamine. Finally, thiazide diuretics such as chlorthalidone (Hygroton) and hydrochlorothiazide (Esidrix and HydroDIURIL) have been shown to increase urinary zinc excretion by as much as 60 percent. If you’re taking one of these medications, your doctor should monitor your zinc levels. Zinc can also impact copper absorption, so long-term zinc supplementation should include copper.

Zinc is a small but mighty mineral that plays a hugely important role in human health, especially regarding insulin balance.