Every fall, we brace ourselves for cold and flu season—along with a spike in Covid cases. These illnesses rise at this time of year because we spend more time indoors in enclosed spaces, and germs and viruses—the microbes responsible for the common cold, flu, and Covid-19—may live longer in dry, cold air.

Your first line of defense against viruses is washing your hands, reducing exposure to sick people, and getting the flu shot and other recommended vaccines. Beyond that, there are other proven ways to protect yourself, starting with a strong foundation of metabolic health. While it’s nearly impossible to stop ourselves from ever being exposed to these viruses, having a healthy immune system can help prevent us from getting sick and spreading it to others by fending off the virus’s ability to replicate in our body. On the other hand, poor metabolic health can increase the risk of more serious infections and complications.

As cold and flu season gets underway—and Covid variants become more transmissible in this “endemic” stage of the pandemic—it’s important to understand the link between your metabolic health and your immune system. Read on to learn how to optimize your metabolic health to strengthen your immunity.

Are there links between metabolic health and immunity?

Metabolic health is how well we generate and process energy in the body, including the mechanisms that convert nutrients from the food we eat into fuel for our cells. Glucose is the precursor to this energy, and we need to keep our glucose in a healthy range for optimal metabolic health. That means choosing nutritious whole foods, exercising regularly, getting enough sleep, and maintaining a healthy weight.

The immune system is a complex network of cells, tissues, organs, and proteins (such as antibodies) that work together to protect us from infections caused by bacteria and viruses. To keep our immune system functioning optimally, we need to do the same things that we do for optimum metabolic health—eat well, sleep enough, exercise consistently, and maintain a healthy weight.

The immune and metabolic systems might seem like separate entities, but they are deeply intertwined. We’ve long seen evidence that metabolic health can affect how we fend off viruses. Researchers referenced the connection between diabetes and complications from the flu as early as the 1970s. A 2016 study showed that understanding human metabolism can help us better understand how viruses affect us because viruses rely on our body’s own cells and metabolic mechanisms to replicate when they enter our body; understanding our metabolism gives us a better understanding of how viruses take advantage of us.

More recently, a study of almost 30,000 adult COVID-19 patients across 135 hospitals found that metabolic syndrome—a cluster of conditions that includes high blood pressure, high blood glucose, some measure of excess fat, and abnormal cholesterol levels—was linked to a 32% increased risk in admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), a 45% higher risk of mechanical ventilation, a 36% increase in acute respiratory distress syndrome, and a 19% higher death rate, as well as more extended hospital and ICU stays overall.

Another study analyzed data from two extensive national surveys and found that adults with diabetes who died between the ages of 25 and 64 were more likely to have pneumonia and influenza recorded on their death certificates than similarly-aged adults without diabetes.

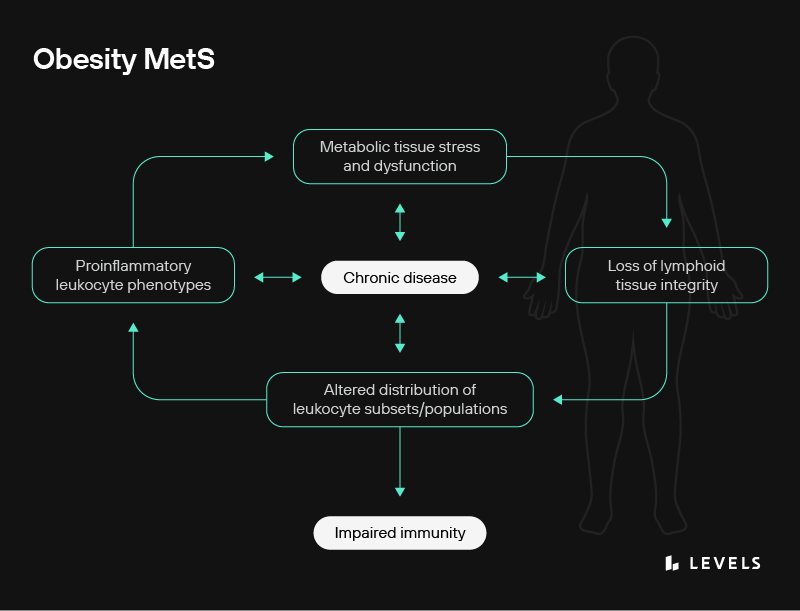

Obesity and metabolic syndrome are associated with stress and dysfunction of metabolic tissues, including adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle, and pancreas. Systemic dysfunction from obesity-related complications leads to fat accumulation in primary lymphoid organs, resulting in a breakdown of tissue architecture and integrity. Obesity-induced changes in lymphoid tissues are further associated with an altered distribution of leukocyte subsets and populations and greater numbers of leukocytes with proinflammatory phenotypes. Obesity-induced disruptions in the immune system impair immunity and contribute to the progression of metabolic dysfunction and chronic disease. Chronic disease can further perpetuate dysfunction throughout the immune system. Source

In addition, people with obesity who were vaccinated against the flu had twice the risk of becoming sick from the illness as vaccinated people at a healthy weight, research shows.

Another study found that obesity is associated with considerably longer infectious periods for specific flu strains. Another found that obese hosts have a delayed and blunted immune response to the flu. According to a 2020 paper, the extended period of contagion could be caused by a few factors:

- Obese subjects shed the virus more than twice as long as non-obese people.

- A higher risk of novel virulent strains develops in obese patients because the delayed and blunted immune response observed in obese hosts allows for more viral replication.

- An association between a high BMI and a greater number of infectious particles in the subject’s breath.

How does metabolic health affect the immune system?

The factors that connect poor metabolic health to an increased risk for severe cold, flu, and COVID-19 aren’t fully understood. But there do appear to be a handful of mechanisms that are at play simultaneously, including:

1. Dysfunction in immune cells

There is a known link between metabolic health and immune signaling. For example, the insulin resistance and hyperglycemia present in Type 2 diabetes can affect cellular immunity in various ways.

- High blood sugar can interfere with the body’s ability to produce cytokines, which can offer substantial protection against pathogens and play a role in antibody production (note that cytokines can also drive an unhealthy inflammatory response in some circumstances and contribute to metabolic syndrome).

- Hyperglycemia can interfere with natural killer cells, immune cells that destroy invading pathogens.

- T cells, a key type of immune cell, may function less efficiently in obese subjects, impairing the body’s ability to fight off infections, as suggested in a study on mice.

2. Nutrient deficiencies

Metabolism is our body’s ability to take the nutrients from the food we eat, break them down, absorb them, and convert them into usable energy. If we’re not getting the proper nutrients—for instance, if we’re eating processed foods that lack essential vitamins and minerals—we can become nutrient deficient, which can negatively affect our immune system. Research finds that undernutrition is linked to immunosuppression, meaning that the immune system is less protective and a person is more susceptible to infection due to a lack of nutrients critical for fueling immune cell proliferation and function. Several other studies show that iron deficiency impairs T-cell proliferation and lowers the production of cytokines, the cell-signaling molecules that help prompt our immune system to respond to infection or illness.

3. Increased chronic inflammation

Chronic, low-grade inflammation has a bi-directional role in several metabolic conditions, including obesity, heart disease, and diabetes. Research shows that obesity, for instance, can increase inflammation and that this can hinder the immune response and affect the coordination between the different branches of the immune system. In addition, inflammation can worsen metabolic function, driving more fat storage and insulin resistance in a vicious cycle.

One example of a specific metabolic-mediated immune consequence is in macrophages—immune cells responsible for detecting and destroying bacteria and other invading organisms. They are found in metabolic tissues and play a vital role in initiating, maintaining, and resolving inflammation. When they become impaired because of cellular metabolic dysfunction, it can lead to increased inflammation, which can make you more susceptible to infection.

Metabolic dysfunction due to overnutrition can also reduce the generation of regulatory T cells (also called Tregs), which help distinguish between your cells and outside invaders. This reduction in regulatory T cells can contribute to an increase in inflammation. Tregs are also necessary for helping to prevent the dangerous inflammatory cytokine storm that is often the cause of death in COVID-19 infections.

4. Oxidative stress

Metabolic conditions are linked to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS). These highly reactive chemicals can lead to oxidative stress and systemic inflammation in the body. Oxidative stress plays a role in the severity of illness and infection and in the innate immune system, which is the part of the immune system that acts as a first line of defense against infection. For example, a 2021 study speculated that oxidative stress might play a role in the severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome suffered by many Covid-19 patients.

What can you do to improve immunity during cold and flu season?

It’s essential to take steps to improve your metabolic health on an ongoing basis, and it’s especially vital to do so during cold and flu season to support your immune system and help fight off infection. The following strategies can help defend you against whatever virus or bacteria might come your way—a cold, flu, or Covid—and help keep your metabolic and immune health strong.

Eat to support healthy blood sugar: For all the reasons above, there’s a clear link between hyperglycemia, immune dysregulation, and an increased risk for severe infection. Eating to support healthy blood sugar levels is a great way to help protect yourself against cold and flu season. You can start by avoiding 10 of the worst foods for blood sugar—like cereal, acai bowls, and other refined carbohydrates—and instead focus on a wide range of foods unlikely to spike your blood sugar, like nut butters, tofu, and guacamole, as well as plenty of fruits and vegetables.

Optimize vitamin D levels: Maintaining adequate vitamin D levels—defined as 50 nmol/L (20 ng/mL) or above for most people—can support your immune system. A 2022 systematic review of 38 studies showed that vitamin D supplementation was associated with a significantly lower risk of Covid-19 severity, an association the authors think may be explained by the fact that vitamin D can act as a modulator of the immune system response through the induction of antimicrobial peptides and the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. A meta-analysis that analyzed data from roughly 11,000 participants from more than a dozen countries found that daily or weekly supplementation with vitamin D in those with levels of less than 10mg/dL cut their risk of respiratory infection in half. You can get vitamin D by eating egg yolks; oily or fatty fish like sardines, halibut, and mackerel; and liver, and through direct sunlight on your skin, which causes your body to produce the vitamin naturally.

Get optimal sleep: Sleep loss is associated with an increased risk of infection, chronic inflammation, cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, and autoimmune disease. When we sleep, our bodies also produce immune cells, such as T cells, which are white blood cells that play a critical role in our immune response to an infectious disease. At least seven hours of sleep a night is recommended. In one study, researchers infected healthy participants with a cold virus and found that about 39 percent of those who slept 6 hours or less got sick, compared to just 18 percent of those who slept more than 6 hours.

Reduce stress: We’ve known for decades that psychological stress is a risk factor for the common cold. A study found that being under severe chronic stress for more than a month doubled a person’s risk of catching a cold. Interestingly, studies show that acute stress may cause enhanced immunoprotection, but long-term stress suppresses or dysregulates innate and adaptive immune responses by altering cytokine balance, triggering low-grade inflammation, and suppressing the activity and function of immunoprotective cells. To reduce stress, try diaphragmatic breathing. A study of people with Type 2 diabetes showed that a program of daily 20-minute diaphragmatic breathing exercises reduced fasting blood glucose and post-meal glucose levels in nine weeks.

Exercise: Physical activity has been linked to a decreased risk of getting a cold. One randomized controlled 15-week exercise training study showed that exercise significantly reduced upper respiratory tract infections. Working out boosts the activity of natural killer cells, essential to the immune system’s ability to fight infections. Even low-intensity exercise like walking is beneficial.