The Study:

“The Effect of a Single Bout of Continuous Aerobic Exercise on Glucose, Insulin and Glucagon Concentrations Compared to Resting Conditions in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression”

Published in: Sports Medicine, April 27, 2021

Where: Imperial College London

The Takeaway:

Moving after meals is good for metabolic health.

What It Looked At:

This study investigated how a single bout of continuous cardio for more than 30 minutes impacts glucose regulation and other hormones that influence long-term metabolic health. The exercise had to be at least 30 minutes at a fixed intensity on a treadmill (walking or running) or cycle ergometer.

The paper is a meta-analysis, which gathers many similar studies together (in this case, 51) and compiles their data to reach broader conclusions than you could with a single study.

This paper did a couple of unique things. First, it focused only on studies done in people without a diagnosed metabolic condition. Many similar previous analyses just looked at people with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes.

“Researchers found that doing any cardio, regardless of intensity, within six hours of eating significantly decreased glucose and insulin levels relative to a resting state.”

“Therefore, these prior studies are not reflective of individuals at risk of developing Type 2 diabetes,” says lead author James Frampton, a PhD candidate in the Department of Metabolism, Digestion, and Reproduction at Imperial College London.

The study also looked not just at glucose but also at insulin and glucagon, hormones that help keep blood sugar stable by either raising it or lowering it. When you have too much circulating glucose, insulin helps it move into fat, muscle, and many other cell types. Glucagon, on the other hand, raises blood sugar levels by converting stored glycogen into glucose. “Glucose homeostasis is a very strong and important risk factor for [metabolic] disease progression over the long term,” Frampton says. For optimal health, we want glucose to be relatively stable and in a healthy range throughout our lifetime.

What It Found:

The most helpful takeaway came in the analysis of the subgroups—specifically fasted versus post-meal. Researchers found that doing any cardio, regardless of intensity, within six hours of eating significantly decreased glucose and insulin levels relative to a resting state. In contrast, there was no significant change in glucose or insulin when exercising in a fasted state. These results were similar across age groups and between men and women.

The researchers had a few hypotheses for the glucose decrease:

- Exercise causes muscles to move glucose transporters from inside the cell to the cell membrane to facilitate glucose entry.

- Exercise can also increase insulin-dependent glucose uptake, lowering glucose levels.

- An increase in blood flow, and therefore glucose, to skeletal muscles allows for increased clearing.

In terms of reduction of insulin with activity after meals, the authors posited that:

- Exercise allows muscles to take in glucose without insulin; that decreases overall glucose levels, therefore decreasing the overall amount of insulin needed.

- Exercise may increase insulin sensitivity, so the muscles can take in more glucose with less insulin.

- Exercise may help insulin clear from the bloodstream more quickly.

- Because exercise causes muscles to get more blood flow, they also get more insulin; this means the pancreas doesn’t have to produce as much.

The glucagon results were not surprising: Levels increased after exercise, likely because working muscles absorbed glucose from the bloodstream, lowering glucose levels and spurring glucagon release.

Why It Matters:

The study suggests that a simple walk after a meal has tangible benefits, not only to blunt the immediate glucose response but also to significantly lower insulin. High insulin responses after a meal can be a sign of developing insulin resistance, a strong risk factor for diabetes and other chronic conditions.

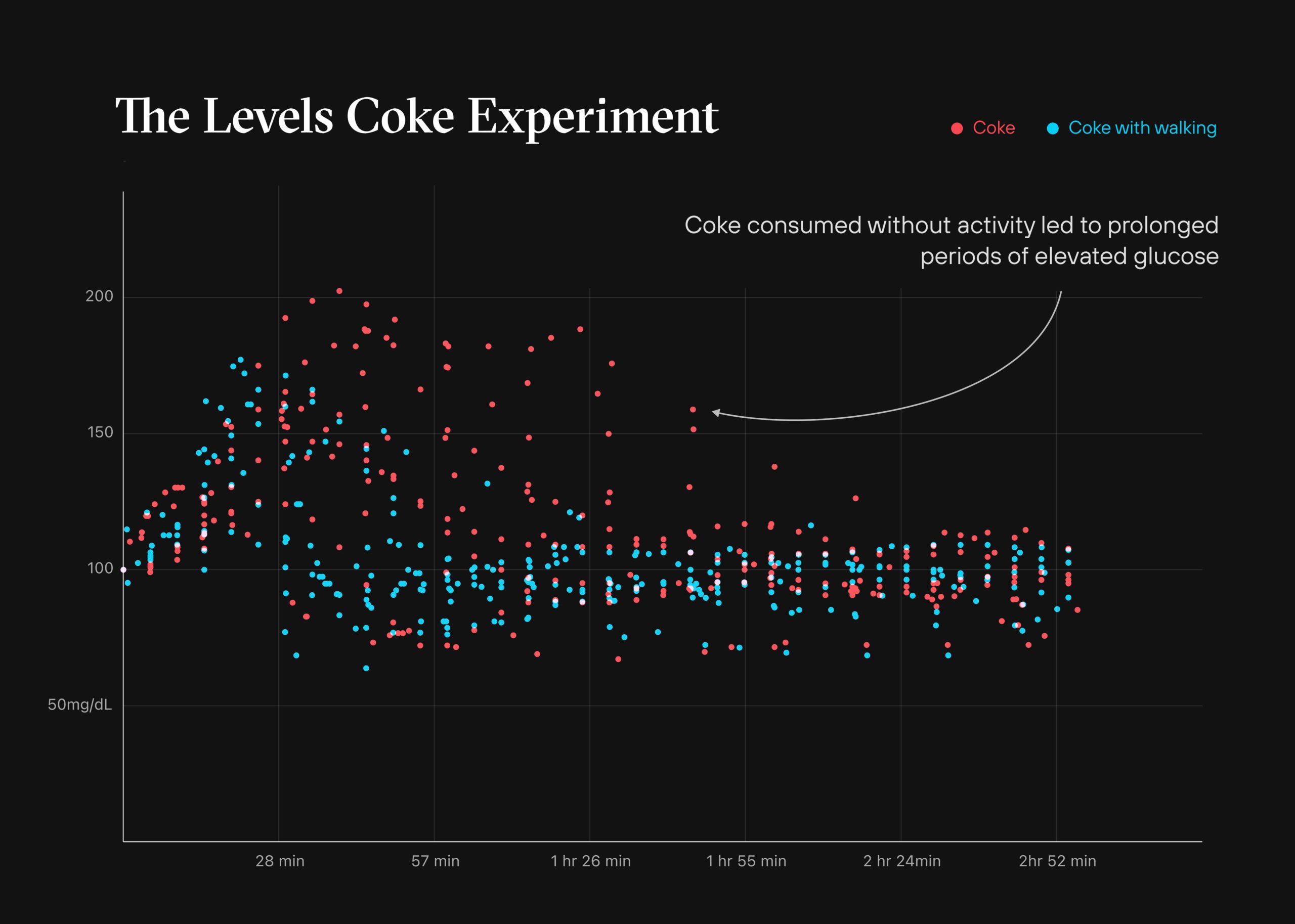

What a can of Coke—with and without a walk after—does to your blood sugar

In the first Levels internal experiment, we found that a simple walk helped mitigate the blood sugar spike from a can of soda.

Read the ArticleThis study does not imply that exercising after eating is better than exercising fasted (in fact, some studies show exercising in a fasted state has metabolic benefits). Instead, Frampton notes, it shows that exercising after a meal has a positive impact on glucose and insulin levels compared to not being active at all after meals.

In their next study, Frampton and his team will compare fasting versus fed exercise, measuring glucose, insulin, and glucagon levels every 15 minutes up to two hours after exercise, in both fed and fasted states. The goal is to tease out whether there are particular longer-acting benefits to exercising after a meal versus exercising fasted.