Dr. Howard Luks is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine. For 20 years, he served as the Chief of Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy at New York Medical College. His book, Longevity…Simplified: Living A Longer, Healthier Life Shouldn’t Be Complicated, published in 2022, provides an uncomplicated, sustainable approach to longevity, helping readers gain more high-quality, fulfilling years.

Levels chief medical officer and co-founder Dr. Casey Means talked to Dr. Luks for a recent episode of our podcast, A Whole New Level. Below is an edited version of that conversation.

A “Biological Issue”

Dr. Casey Means: Thank you so much for being here. I am really one of your biggest fans. I love what you are doing to change the way we think about a subspecialty like orthopedics or orthopedic surgery, broadening our understanding of joint health and musculoskeletal health.

We have done some content work together for the Levels Blog. I’ve shared your blog posts about the relationship between metabolic health and joint health with so many people. But then, more recently, I personally reached out to you because I think you’re the only orthopedic surgeon in the country with whom I feel philosophically aligned. I was doing back squats, and I ripped a 1.5-centimeter piece of cartilage off my femoral head cartilage.

I went to the orthopedic surgeon, who strongly recommended this two-stage, very invasive surgery called a MACI procedure, which would have me harvesting cartilage, growing it in a lab, and putting it back in my knee. It did not feel right to me. It felt like a very turbo decision for a young person who was not actually in that much pain.

I emailed you and asked for your recommendation. When you hear something like that—someone’s had a cartilage defect in their knee—how do you approach it?

Dr. Howard Luks: Great question. It doesn’t have an easy answer. We are so much more than a simple finding on an MRI. We fail to understand what typical findings in an orthopedic practice are for active people squatting heavy weights or running long distances. Is it unusual to have a small lateral chondral cartilage defect? No, it turns out.

As I’ve shared with you, I got MRIs of both knees long ago solely because I wanted to see them. I was interested. I have meniscus tears and cartilage defects, and bone marrow edema in both knees, yet I was actively running 30 to 40 miles a week. I still am.

We dove into your process. You had little to no pain and were ready to go back out and start working out and moving. We learned that this may have been the day you realized that you had a defect, but it may not have been the day the defect came about. We didn’t see edema or inflammation in the bone. We didn’t see sharp edges around the defects. There were a lot of hints there that maybe it wasn’t acute. Maybe we were seeing the early part of a more—I hate the word—degenerative process, just one of those things we accumulate through the decades. This is especially true for people with poor metabolic health, which we’ll touch on later.

You were feeling fine. It’s very hard to cut into the knee of someone who’s feeling fine and expose them to the risks of surgery, the risks of complications, and the risks of just opening the knee. The knee doesn’t like that. No joint likes that, and it will degenerate a little just because of that.

I was part of the original research done on this cartilage-based procedure in New York City at the hospital for joint diseases. We found that a lot of these defects recurred. If we were doing them on degenerative defects or defects that were coming about—not because of an acute trauma, but over time—they would come back again a few years later.

We put out the fire. We put out the thought that, “Oh, my God. I have to fix this immediately.” You stepped back, and you’re doing fine. We really don’t have research saying we’re heading toward arthritis or a future problem. I really hate the idea of trying to do something now: we might affect something in the future, and we might not. If something bad happens now because we did this, then you’re definitely going to have a problem in the future. And look at you. You’re doing wonderfully.

Dr. Casey Means: It was an amazing conversation because you shared with me what you said, that you can take a lot of patients who are older or even young, and do MRIs of their knees, and some people may have structural architectural defects in the knee—or in any joint. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they all have symptoms.

That’s very different from how we typically think, in the surgical world, “There’s a structural problem. We must fix it.” I’m going to read a note you sent me because I love it, and I’d love for you to unpack it a little bit more:

“It turns out that cartilage issues and early osteoarthritis are often the results of a failure of the innate repair mechanisms that cartilage has. In other words, osteoarthritis is not a mechanical issue; it’s a biological issue.”

Many people think about osteoarthritis as bone-on-bone—it’s cartilage degeneration. What do you mean by a joint issue being more of a biological issue than a mechanical one? Where does that give us room to intervene in a different way?

Dr. Howard Luks: Great question. For the longest time, you were told, “Don’t run. It’s going to ruin your knees. If you have this sound, you’re grinding away cartilage.” It’s very easy to think of cartilage as cheese on a cheese grater or sandpaper on wood and that these horrible things are happening inside our knee when we run, or when we move, or when we work out. Well, it turns out it’s not. It turns out that osteoarthritis, in the majority of situations, is a failure of a biological repair mechanism. Cartilage is capable of repairing itself, but something screws up the pathway.

We’re not quite sure what’s going on there. I am not a researcher in this space. I do follow it closely, though. The Wnt signaling pathway is one of the pathways involved in repair. There are new Wnt inhibitors, small protein molecules, that they’re administering to people in Phase 3 studies. They’re showing that they can halt—and at times reverse—early changes associated with arthritis. The changes in an arthritic knee are much more complex. The ideology or the cause of osteoarthritis is far more complex than we were initially led to believe.

Dr. Casey Means: Of course. I was thinking, “I want to do anything non-operative that I can possibly do before having someone cut into my knee,” which is ironic, as I trained as a surgeon, as you did. A group of us know that’s a powerful tool, but also believe that, if there’s anything we can do to stay out of the operating room, that’s ideal because it is a very morbid act.

Having surgery is almost like a rite of passage in the Western world. But when you’re actually in that room, a crazy thing is happening. You’re cutting into someone’s body, causing huge inflammatory responses—a huge stress response. We want to avoid it.

I was doing some digging, thinking, “What’s going to lead to degeneration? Maybe failure of the regenerative pathways, and maybe an over inflammatory response that’s not well regulated.” There’s some research showing that maybe fish oil or anti-inflammatory strategies can help with joint health. How do you think about the various behavioral modulators of healthy joint biology? Is there anything you recommend for patients to essentially create conditions within the joint that lead to the more regenerative capabilities of our tissues?

Dr. Howard Luks: What I try to get through to patients is that our joints are no different than our liver, heart, brain, pancreas, eyes, kidneys, et cetera. Poor metabolic health, poor glucose control, fatty liver disease—now of epidemic proportions—lipid issues, triglycerides… These are causing a cascade of events. Our musculoskeletal system, tendons, ligaments, and bones aren’t sitting by, unscathed. We have a higher risk of osteoporosis. A 50- or 60-year-old woman is going to spend more time in the hospital because of osteoporosis than heart disease and breast cancer combined.

One in three women over 50 is going to suffer an osteoporotic fracture. One in five men is going to suffer an osteoporotic fracture. Men are going to suffer, too. We are more prone to having tendon and ligament tears when we have poor metabolic health.

Your hemoglobin A1C is the glucose floating around your body. It sticks to things. When it sticks to hemoglobin, your A1C goes up. It sticks to other things, too, and if it does that in your eye, it leads to blindness. If it does it in your kidneys, it leads to kidney failure, and on and on. If it sticks to parts of your tendons and you have hyperuricemia, or high uric acid—if you have lipid or cholesterol deposits—then you’re taking away collagen or tissue that forms tendons and ligaments. You have an increased risk of rupture, because those tissues are weaker.

Poor metabolic health, as you well know, causes an increase in systemic inflammation. That inflammatory burden is going to affect our knees. People with diabetes or severe insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome have more pain with mild osteoarthritis than someone who’s metabolically fit or healthy. This may be why osteoarthritis and other conditions, which are inflammatory in nature, worsen a little more in people with poor metabolic conditioning and health.

I can’t tell you how common it is: I have someone in front of me. Their A1C is eight, AST/ALT in the 40s, high triglycerides—poor metabolic conditioning. I bring a lactate meter to my office sometimes, to check the baseline lactates. We dive into metabolic fitness and health. They’re oftentimes coming because something’s bothering them. They’re concerned: “Do I have a meniscus tear? Do I have this?” I’ll dive deeply into why they’re experiencing symptoms, why it’s not what their MRI shows, and how we’re going to fix this. We’ll dive into nutritional strategies, exercise strategies. I am not going to stop their exercise. It’s a tough way to practice medicine these days, isn’t it?

Poor metabolic health causes an increase in systemic inflammation. That inflammatory burden is going to affect our knees. People with diabetes or severe insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome have more pain with mild osteoarthritis than someone who’s metabolically fit or healthy.

Dr. Casey Means: It’s definitely going against the grain. As we know, spending that time to understand a patient’s diet, lifestyle motivation, and barriers to healthy living takes a long time. It’s not financially incentivized. Whereas, if you take them in for that really fast arthroscopic procedure, that is going to bill gangbusters. It’s fast—they’re in and out. You don’t have to have those long conversations.

We both know there’s such a bias toward action because of the way our system is incentivized. You take a very different route in your practice by really focusing on the underlying biological mechanisms that lead to outcomes, for which we sometimes think operations are our main hammer.

Keep Exercising, and Don’t Panic

Dr. Casey Means: Let’s dig in a little bit more to movement and exercise. You said you do not tell people to stop exercising, even if they have a joint issue. That was really empowering to me when you mentioned that, because right when I hurt my knee, one of the most disconcerting symptoms was this constant clicking every time I bent my knee and took a step. I thought, “Oh my gosh. This feels to me like I need to have surgery to cut off whatever is causing that clicking.” It’s a very uncomfortable sensation. There was a little bit of pain, maybe two out of 10. Now, four months later, I have zero clicking, absolutely zero pain, and full range of motion.

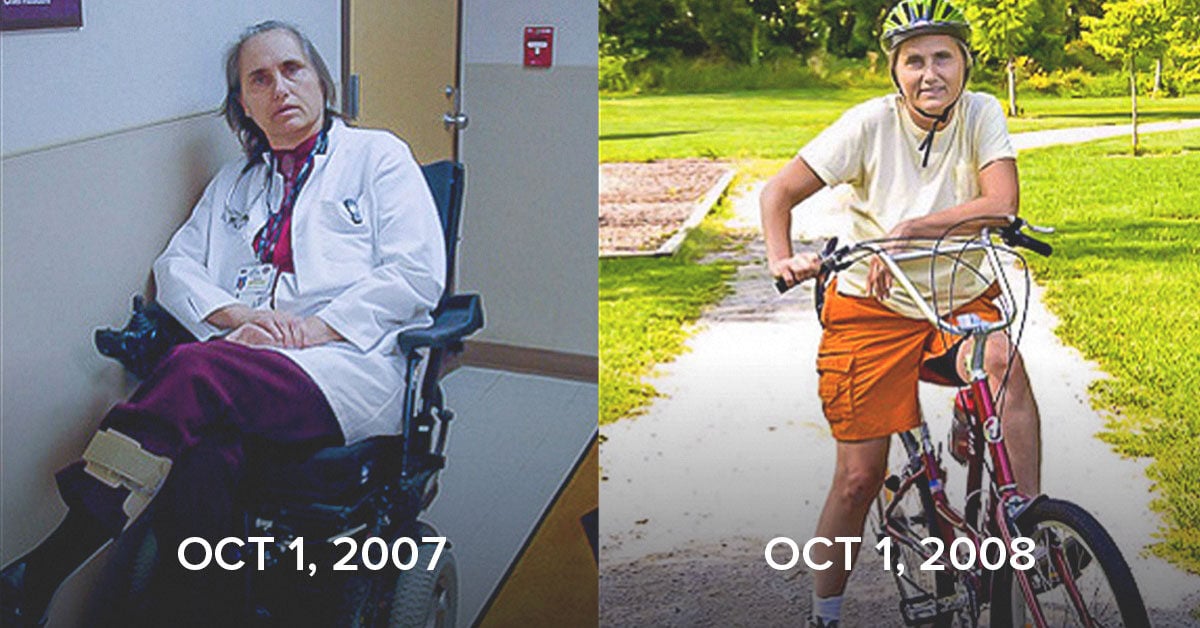

In part because of your prompting and other reading, I’ve been extremely active—not pushing through pain, but not letting slight discomfort totally deter me. In my mind, before understanding this a bit better, I thought, “If I’m moving and exercising, it’s going to cause more inflammation in my knee, and that might be a bad thing.” But can you explain why that’s probably not the right way to think about it? What is a framework for staying active despite having some joint issues?

Dr. Howard Luks: There’s lots to unpack there. First of all, there is no 40-something, 50-something, or 60-something walking out of an operating room who is going to feel better in two weeks, or even six weeks. They may regret having the surgery in six or eight months. We just do not respond quickly. It’s almost never a quick, easy answer to something that’s bothering us.

Next, it’s very hard to unsee your MRI. If you throw a 40-, 50-something in for an MRI, you’re getting back a report that shows many things—a little bit of this, a little tear of this, some fraying of this—and people don’t like that. Now, every time the knee hurts, it’s going to of course be because of that little thing on the MRI.

There are very few reasons to stop exercising. Unless someone has a stress fracture, or something that’s going to actually worsen, there is no reason to stop. It is a common misconception that with osteoarthritis you are causing more harm if you remain active, yet the exact opposite is the case.

Osteoarthritis is less common, according to the evidence, in runners. Maybe that’s a self-selection bias, because runners keep running. However, they did a study where they x-rayed a bunch of runners and non-runners with the same degree of osteoarthritis. They allowed the runners to run at a self-selected pace. The sedentary people remained sedentary. The sedentary group was more likely to have a knee replacement than the group who was running.

It turns out that the cartilage likes cyclical loading. Cartilage is not a dead tissue. It’s not a sedentary tissue. It’s like a sloth: it doesn’t move quickly. It’s not exciting, it doesn’t beat, it has a very slow metabolism. But it is capable of repair. There is a nourishment process going on. That nourishment comes not from blood flow, but from substances in your joint fluid. The cyclical loading actually helps to get that nourishment and energy source into the cartilage. Maintaining a level of activity is super important. I care a lot about bones and fracture risk, and it’s really important to stay active because it improves your bone quality and lowers your osteoporosis risk.

It is a common misconception that with osteoarthritis you are causing more harm if you remain active, yet the exact opposite is the case.

More importantly, if you are exercising and you’re used to exercising and you rest for as little as two weeks, you’ve lost about 20% of your muscle strength. Not only that, metabolically speaking, you also become more insulin resistant. There are very few reasons to stop people from exercising. Most people in my office, if you talk to them properly and ask the right questions and listen to them, are more concerned that they’re not doing harm. They’re not there because the pain is so acute that they have to do something. They’re there because something hurts. Their best friend said, “If you continue running or playing tennis, you’re going to kill your knees.” Their primary carer might have said the same thing.

Doctors are guilty of this, too. The main message to them is, “Look, you’re okay. We’re not going to get an MRI, because it’s not going to change what I’m going to do, and the result is going to freak you out. I want you to stay active. I don’t want you to decondition. If the pain ever gets to the point where it is the reason you need to stop, then we need to talk.”

Dr. Casey Means: That makes a lot of sense. Pretty much everyone has some ache and pain at some point in their life. And their doctor has probably encouraged them to have surgery because that’s the hammer that we’ve got. How do you think people should think through pain? What’s the mental model people should feel empowered to latch on to before making the decision to go under the knife? And are there circumstances in which you would say the best option is to have the surgery?

Dr. Howard Luks: I’m not telling people not to come to the office. If you have a concern, I want to see you, and I want to see what’s going on. If you listen to someone, you’re going to know the diagnosis. Then your exam is going to confirm that. We don’t need an MRI for a diagnosis. We often get it to confirm a diagnosis based on our suspicion. Based on your examination and your complaints, we’ll decide if an MRI is necessary or not. Based on your symptoms, we’ll then decide on what the best path forward for you should be. Maybe that means continuing with your activities, or slowing down for a little bit. Maybe it means speeding up to do more resistance training, and less aerobic work, or maybe some more bike work or swimming as opposed to running.

What’s really important for people to understand is that more often than not, you have a lot of choices. You have time to decide. Very little in my world is an emergency. If I see people with an acute traumatic injury—terrible weakness of the shoulder, they can’t move it or I’m suspicious that they dislocated it—I’m going to get an MRI. I want to know if you have a large rotator cuff tear. If it’s tiny, I’m probably not going to say to do something. If it’s huge and you’re young, I probably will advise it. But again, these are not life-or-death struggles in the orthopedic world. You do have options.

If I’m concerned you had a patella dislocation, I’m going to MRI you, because I want to make sure you don’t have a cartilage injury associated with that. For ACL tears, I’ll get an MRI not to confirm the ACL tear—because my exam will tell me that—but to look for concomitant injuries to other structures that may need attention.

But the vast majority of joint pains and aches do not require surgery. Many don’t require advanced imaging. They require us to listen to you, to examine you, and come up with an appropriate plan. I’m not blowing you off. I’m not ignoring you. I’m going to distract you while mother nature heals you.

Dr. Casey Means: I remember reading, when I hurt my knee, about chondrocytes, the cartilage cells. You said that they’re not only sloth-like, but that they’re basically these inert cells that don’t regenerate, and they are just dead, almost. I know that some of the cartilage doesn’t get great blood flow, but you were mentioning that it’s actually some of the factors in the fluid around the cartilage cells that is actually producing some cellular signaling.

Can you paint a picture of how cartilage cells operate in terms of metabolic activity? Do they have mitochondria? Do they respond to regenerative or anti-inflammatory factors that might be circulating in the fluid around them? Or are they just dumb dead tissue? I think the answer is no, from what I’ve read. But I’d love for you to unpack it.

Dr. Howard Luks: The more you know, the more you realize you don’t know, right? Every time I think I’m out of the valley of despair of the Dunning-Kruger curve, you just slide a little bit back into that valley. I should be all the way up on the right somewhere. But you realize that medicine is far more complex than basic pathophysiology and biology. There’s so much more in the textbooks now than there was when I studied, probably even more than when you studied. It changes every day.

We used to just think of cartilage as this smooth, rubbery substance, and that it was dead and didn’t really do much. It just wore away over time. It’s not exciting. Although, when you put a scope in the knee, or when you open the knee, it’s a beautiful substance. it should be white, pristine, perfect, smooth. There’s no surface in our body with less friction than joint cartilage. It really is a wonderful tissue.

It doesn’t like to be sewn. It doesn’t like to be invaded. It doesn’t like to be hit, because it has such a slow metabolism. If you strike your knee against the dashboard in a car accident now, you may have some pain that’s eventually going to go away. In three years, you may have a cartilage injury. It may show up on an MRI. It was because of that injury three years ago, because it took so long for the ramifications of that injury to reveal themselves. Cartilage cells like to stay by themselves. They don’t like others, and they secrete this matrix, the white substance. There are mucopolysaccharides and other things in there. That’s what forms this hard, gelatinous, smooth surface.

What is in your blood—based on your metabolic health, fitness, overall health, and what you’re eating—is what’s going to be filtered into your joint fluid. And that’s going to be compressed into your cartilage. We are completely connected. We can’t think of cartilage as being different from a kidney, an eye, a heart, or a liver.

Embedded in there are the cartilage cells. They do not have a blood supply. In a non-arthritic knee, they do not have a nerve supply. In late stages of arthritis, we can develop nerves, et cetera, and that’s a source of pain. But that’s a different subject. It has no source of nutrition coming from the underlying bone or from blood vessels through the bone into the cartilage. Blood vessels and nerves do not cross through the bone to which the cartilage is attached. They do not get into the cartilage.

Cartilage cells are subject to the limitations of what’s in the joint fluid, whether it’s glucose, cytokines, inflammatory mediators, IL-6 (an inflammatory mediator). COMP is a protein that, when present, is a sign of cartilage degradation. Interestingly, if you’re sedentary, your COMP levels go up. If you’re active, your COMP levels in your knee go down. Same with IL-6 levels. What is in your blood—based on your metabolic health, fitness, overall health, and what you’re eating—is what’s going to be filtered into your joint fluid. And that’s going to be compressed into your cartilage. We are completely connected. We can’t think of cartilage as being different from a kidney, an eye, a heart, or a liver.

The Link between Metabolic Health and Joint Health: “No Tissue Gets a Pass”

Dr. Casey Means: That’s amazing. Let’s really get into this relationship between metabolic health and joint health. What are the actual mechanisms that relate poor metabolic health to issues in our joints? On the flip side of that, how does improving or having optimal metabolic health change our outcomes for having pain throughout our lifetimes?

Dr. Howard Luks: The issues people in pain come to the office for often fall into two major groups: bony and soft tissue. The majority of bony issues—joint issues—are arthritic in nature. That’s osteoarthritis. The majority of soft tissue issues involve tendons and ligaments. Ligaments tear, or they don’t. It’s very rarely a problem other than that. A lot of shoulder pain is tenderness. A lot of hip pain is tenderness. You may have heard the term bursitis. It’s far less common than you think.

It’s almost always the tendon that’s the problem. We suffer from tendinopathies—painful tendons, changes within the tendon. The tendon of a 50-year-old doesn’t look like the tendon of an 18-year-old. We can get tendinopathies. That’s the reason we have Achilles pain as a runner, or patella tendon pain as someone who plays in running sports. Shoulder pain, that awful pain on the side of your shoulder when you reach up, or at night when you roll over, the side of your hip that’s just killing you—these are tendinopathies. Tennis elbow is another tendinopathy.

Why does everyone between the age of 15 and 65 get tennis elbow? We don’t know, but it does happen. With tendinopathies, some of it may be pre-programmed into us. As I said, everyone gets tennis elbow. I’ve had it. It was a short course. Maybe my fitness had something to do with that, because it can last nine to 12 months in many people.

Tendon is made of collagen. It doesn’t want to be made of anything else, because the strength of that tendon is going to be based on the alignment of that collagen. Imagine a box of spaghetti. When you take the spaghetti out, you see all these little fibers. That’s collagen. Break it up and mix it around. That’s tendinopathy, where the fibers are going in different directions. There’s space between the fibers, and there’s junk in there because of glycosylation or cholesterol deposits, uric acid deposits—all this sludge or junk will occupy space where the tendon should be, and it compromises the tendon’s integrity.

If you overload a tendon, you will develop an overuse tendinopathy. I’m a runner. I like talking about runners. Most running injuries are overuse injuries. We decided we’re going to run faster today or farther today, and we don’t give ourselves enough rest. And a week later, our tendon hurts. Well, if your tendon fibers aren’t properly aligned, if you have all this sludge and other substance in between those fibers, if the inflammatory burden in your system is higher, and if your repair mechanisms are somewhat suppressed by that inflammation, you have the perfect setup to have pain, fraying, tearing, et cetera. The blowback I get online all the time when I talk about this, especially from other physicians in my line of work, is, “What am I going to tell someone who’s 60 years old with a rotator cuff tear? Take allopurinol and decrease your glucose?”

Well, if they want to live to 90, yes, but that’s not going to address the shoulder problem now. This is why the earlier we pay attention to this, the better we’re going to be. You don’t want to bring these tendons and this arthritic burden—this inflammatory burden—through your formative decades and your decades in early adulthood, because they’re going to result in problems.

These are all area-under-the-curve issues. Yes, ApoB is causative of heart disease, and it’s worse in the presence of inflammation. I had to say that. The higher your A1C and your glucose are over a long period of time—again, area under the curve—the worse the downstream consequences: for your eyes, your risk of dementia, your risk of kidney failure, hypertension, NAFLD, fatty liver. In my world, this correlates to a higher risk of tendon-related issues, more severe pain, tendon tears, overuse injuries, and more significant pain with arthritis and other maladies.

Dr. Casey Means: Beautifully said. I love the visual you gave of a tendon with all this collagen, and you want it to be in a nice structure formation. If you start adding a bunch of excess uric acid, cholesterol deposits, glycation through excess glucose sticking to things, you start cross-linking all these things and causing problems in the structure, making it more vulnerable to injury.

I was on a podcast recently, and we were talking about glycation of collagen in the skin and how that’s part of the etiology of wrinkles. It’s fun to think about how many of these mechanisms in the body show up in so many different cell types, or different systems, and are causing dysfunction over the body.

Glycation in the skin could look like wrinkles. Glycation of the ligament could look like a weaker, more dysfunctional tissue that’s more prone to injury. The bottom line is that we want to get rid of these excess metabolic byproducts that ultimately disturb our tissue, and therefore create symptoms and disease.

A couple of years ago, I went to a plant-based physician nutrition conference, and there was an orthopedic surgeon there. One of the things that sticks out in my mind is how he basically said that rotator cuff injuries are like heart attacks of the shoulder. He was talking a lot about blood flow as part of the link between metabolism and one’s predisposition for injuries.

We know that high insulin levels can cause some endothelial dysfunction, and blood vessels do not dilate as well. How does that play into how you think about metabolism’s relationship to injuries you’re seeing in your office?

Dr. Howard Luks: You’re absolutely correct. The downsides of excess glycation affect every tissue. No tissue gets a pass in this. Our cardiovascular system or our blood vessels are terribly affected by the presence of Type 2 diabetes, high glucose levels, high inflammation, hypertension. Our blood vessels thicken—they’re not as porous. Smaller blood vessels are going to close up. They’re going to disappear. We have many areas, in the orthopedic world, that already have very limited blood flow, like parts of the Achilles tendon. That’s why tears almost always occur at the same level on the Achilles tendon, or parts of the rotator cuff.

If in the best circumstances you have a marginal blood supply. In the perfect situation, your arteries overlap a little. But if you start to get arterial disease, you’ve lost blood flow to this area. Where there is no blood flow, there is no cell turnover, there is no repair. You’re not bringing in the building blocks to repair that tissue. You’re not taking away the dead tissue. It’s a dead zone. And that’s at high risk for injury.

I talk about the effects of blood flow with a lot of patients. Everyone’s going to have their moment, the light bulb moment where they say, “I understand this. I get this.” That was the focus in my book: “You’ve heard all this before, you’ve heard this advice before, but here’s why it matters and here’s how it’s all interconnected.”

What happens to stick with men a lot, and why they want to focus on their metabolic health, is impotence. Boom. I immediately get their attention. It’s a blood flow issue. It’s a blood vessel issue. It is related to your poor metabolic health. It is related to your cholesterol levels. And the same issues can be reflected in our tendons and various areas of our body, and absolutely will have a role.

Every time you exercise, run, walk, or do things, we get these micro injuries. The tendon will get a little stretched, a little damaged, but it’s okay. Blood vessels are there. They bring white cells. The white cells will remove the damaged tissue. Other cells will come in and lay down the building blocks into new tissue, and you’ve repaired it. But if you don’t have the building blocks there because there’s no blood flow, if you can’t clear the debris because you don’t have enough blood flow, you’re just escalating the problems.

Dr. Casey Means: Beautifully said. The body is such a dynamic entity. It’s not just this thing that’s there and it gets hurt, so you have to fix it. It’s this dynamic, buzzing hive of communication. And you’re saying that, yes, there are different ways to screw up that communication. You can limit blood flow to the area. You can create blocks in communication by having all these deposits of debris. Much of it, as you’ve beautifully written about, is downstream of metabolic dysfunction: the blood vessel narrowing, or lack of elasticity, the glycation and too much glucose sticking to things, too much oxidative stress, too much chronic inflammation, which we know can be driven by metabolic dysfunction, uric acid buildup, et cetera.

In your practice, when you dig into the metabolic issues with patients and they have their light bulb moment and make changes, do you tend to find better outcomes? What has your patient experience been like with some of this messaging, and with patients who have really adopted this? On the flip side, for your patients who are super metabolically healthy, do you find that they tend to do better over time?

Dr. Howard Luks: Great question. For me, these are my biggest wins in the office. Frequently you’re not just changing one life, you’re changing the whole family’s life, because they’re going to drag their spouse along, they’re actively going to bring their kids outside. Your kids aren’t going to listen to what you tell them to do. They’re going to emulate your behavior. If you’re out there and active, they’re going to be active, too. These really are my favorite cases.

I’m not saying I do it all without surgery. Sometimes that’s necessary—a knee replacement, say. But I’m not bringing you to the operating room with an A1C of seven, elevated inflammatory markers, elevated liver markers, et cetera. We’re going to get you on a path to wellness before we start, and it’s going to improve your recovery. Then you’re going to continue on that pathway, hopefully.

Can I convince everyone? No. Can I convince maybe 15% or 20% who stick with it? I can. It does work, and it takes time. It’s hard. We’ve talked about this, but modern medicine is not built for this. We are complex bodies, but we don’t see any one doctor who puts everything together for us. Therein lies a significant issue. Your cardiologist is going to adjust your blood pressure medicine. Your endocrinologist is going to increase your metformin. Your primary care doctor will give you your flu shot. This isn’t their fault. This is how medicine is constructed. They have to perform. If they don’t perform, they don’t get paid.

I’m not saying I do it all without surgery. Sometimes that’s necessary. But I’m not bringing you to the operating room with an A1C of seven, elevated inflammatory markers, elevated liver markers, et cetera. We’re going to get you on a path to wellness before we start, and it’s going to improve your recovery. Then you’re going to continue on that pathway.

They don’t have the time. They don’t have the ability to sit there and spend an hour with someone with five diseases. I try to spend the time that I have, and it’s usually more than 15 minutes, putting everything together, much like I do in the book. I have some handouts in the office of outtakes from the book. If I see someone sit up and I see they’re interested, I’ll go deeper. It’s not unusual to get some blood tests. It’s not unusual that I’m going to find someone with an elevated LP(a) or early fatty liver. I’ll then refer them to the appropriate specialist, because I’m looking more deeply into them. The take-home message of that statement is, be your best advocate. You have to look deeper and think in a more complex manner, because I don’t think that modern medicine is going to do that for you today. It’s a terrible challenge for us.

Dr. Casey Means: You mentioned how if you change that patient, you’re changing the whole family. The other thing there is that you change that patient’s metabolic health. They come to you through the doorway of orthopedics. You get them tied into why metabolism matters, but then you’re changing their whole body. You’re getting at that root cause.

I can imagine that, as a physician, burnout is at an all-time high right now. Over 60% of physicians are burned out. Suicide is super high. As someone who became very burned out in residency, I’ve thought a lot about this. Ppart of it is that we just don’t really feel like we’re making the impact we want to make. It’s the revolving door. We don’t have time. The incentives aren’t aligned. People aren’t really getting better. There’s a lot of slow worsening over time, despite the interventions we’re recommending.

In the way you’re practicing, I imagine it’s a lot of emotional work for you to go that extra level. But you also see people getting better, and you see their whole bodies getting better. It must be really gratifying to see good outcomes like that, whole body outcomes as well as joint and musculoskeletal outcomes.

A Different Approach

Dr. Casey Means: What do your colleagues in the orthopedic field think about how you’re practicing? It’s the tip of the spear, saying, “No, we don’t just have 42 subspecialties in medicine doing different things. We have common pathways affecting the entire body. If we attack them and approach them and reverse them, we’re going to do better, and maybe even prevent surgery.” That’s pretty revolutionary. How did you become that way? And how have people responded?

Dr. Howard Luks: Economically speaking, when building and training a surgeon, you should keep them operating all day long. Get an MRI with positive findings. Have the patient see the PA. The PA will tell them they need an operation. They say hi to the surgeon. The surgeon operates on them and they see the PA and they’re gone. I get that. I understand the economics.

I’ve just never bought into that. I was never the busiest surgeon. I could have been. I’ll have a four- or five-month backlog for surgeries, but I’ve been very lucky. I was very smart in terms of my saving and investing. I founded a company with two wonderful guys, and we sold it. I was involved with others and had a few exits. I’m working because I love it. It’s that simple. I really enjoy these interactions with people. I love the feedback. And sadly, my one regret is it doesn’t scale.

Everyone says, “Why don’t you fix this? What am I going to do?” I advise a lot of startups. I love working in this space. I like to help people connect the dots. I think I’m good at it, but I don’t know how you scale this practice of medicine. The way medicine is today, you’re just not going to do it.

Healthcare is a huge proportion of our GDP. Everything is aligned against decreasing the number of procedures. It’s a challenge. I’ve had many different responses from colleagues, many of whom dismiss me as a snarky old guy, and many of whom say, “Hey, can you help me?” I probably have about 40 or 50 fellow physicians reaching out saying, “What do you think of this? Do you have an article on this? I’d like to know more about this.” That tells me that the message is resonating with a number of people.

I came to this in a different way than you did. You’re smarter than me. I trained during pre-80-hour work restrictions. It was the most god-awful experience I’ve ever been through. I should have taken your path, but there weren’t even cell phones then. I wouldn’t have known how to meet another founder. I enjoyed being an orthopedist. I was a head of sports medicine at New York Medical College for 20 years. I helped train residents, and really enjoyed that process.

I’ve always liked teaching, not just patients, but colleagues and students. I was always active. I played every sport there was. I was always outside. I don’t sit still well. I enjoy running, trail running, hiking, et cetera. My dogs were there with me. Then I had my second child and we got a little overpowered at home and work got a little busier—call schedules with raising a child, et cetera. All of a sudden, my weight was up a little, and I had a little belly pain.

One day I was hanging out with the chair of radiology. He told me to lie down. He said my gallbladder was fine, but I just had a little fat in my liver. I’d weighed 173 to 175 pounds since high school. All of a sudden, at that point, I was 196. I still have those pants in my closet as a reminder. There wasn’t much in the literature back then about fatty liver, but I started to go down all these pathways. What’s associated with fatty liver? What’s its cause?

I said, “Uh-oh, this is your moment. You’re going to turn 40 soon. I’m not quite sure why this is here, but this is not good for you.” I cut out all the crap from my diet. We didn’t have keto or low-carb rabbit holes back then, but I just went on a whole-food diet. I ate real food, mostly veggies, and stopped drinking and started running and exercising more. I was optimizing for my longevity.

I’d started a website around that time. At first, I was writing articles because I just wanted to share them and tell people what I thought. Then I learned by writing, and I started to read about fatty liver. I started to read about insulin resistance, cholesterol issues. The more I read, the more I started to write. I started to publish these articles, the same thing I do in the training space.

Eventually, I wrote enough that people said, “You need to write a book.” One thing had turned into another. I never really had the time to write a book, but then this little virus came around and I found the time to write the book and here we are.

I came to this—like most people, probably—my own issues with health, and a threatened longevity or health span.

Dr. Casey Means: How did you put the puzzle pieces together? You’re dealing with some fatty liver, you get things back on track, you become a newfound metabolic health evangelist. How did you start making the link to the orthopedics world? Was it just starting to go on PubMed deep dives? Was it starting to see some patterns?

Some doctors might get sick and think, “Just like most 50- or 60-year-olds, I have fatty liver and my glucose levels are going up. That’s great. I’m just going to keep practicing cardiology or neurology the exact same way I’ve always been.” You actually said, “Whoa, there’s a relationship here.” That takes quite a different way of thinking. What was that link for you?

Dr. Howard Luks: That was very challenging because, as you know from medical school, we’re not taught this way, either. We’re not taught that everything’s connected. We’re not taught about attrition, diet. We’re taught that exercise is good for you, but not why.

It took a lot of reading. I just like to read. I found this very interesting, and I was incentivized. I had two little kids at this point. I was a 38-year-old with this fat in my liver. I had no idea what was going on. I was obviously overweight, and I didn’t like how I looked. I didn’t like how the future looked. The more I read, the more the interest grew. One thing just led into another. It snowballed. I don’t know why I made the connection to the orthopedic space or the musculoskeletal space. One day I realized these systems were not different from the rest of the body.

Just because you have all this stuff in the center and things that beat and move doesn’t mean that everything out in the periphery isn’t connected as well. The more I started to read about it, the more I realized, “Hey, it is.” I read more and wrote more.

Dr. Casey Means: I love that. That sounds so familiar. For me, in the ENT world, it felt like a little silo. It was as if the ear, nose, and throat were separate from the rest of the body. There’s just no recognition that it could possibly be related to anything else.

I vividly remember a New England Journal of Medicine article that had a beautiful illustration of the sinus tissue and all the cytokines that were upregulated in chronic rhinosinusitis. I thought, “Wait a minute, I’ve seen all these words before,”—TNF alpha and interleukin-6 and whatnot. I opened up one of my med school lectures about heart disease and diabetes and thought, “It’s all the same cytokines. How is the nose inflammatory response the same as the systemic inflammatory response for this stuff?”

Then you start going down the rabbit hole. I just started Googling, digging into PubMed: sinusitis, diabetes; sinusitis, heart disease; sinusitis, obesity; sinusitis, dementia. There were papers on all of them, basically showing that you have twice as high of an odds ratio for any of these metabolic-associated diseases with sinusitis. It was one of those moments where you think, “Wait, what? How could these possibly be related?” Then of course you can’t unsee that. It’s such a fun journey, and there’s no subspecialty for which that type of epiphany can’t happen because, like you said, we are a completely unified system.

Dr. Howard Luks: Then you get to a point where you realize it’s all connected, but how far down this rabbit hole are you going to go? I don’t know where to stop. It’s really fascinating. Everyone gets about 78 to 80 Thanksgivings in their life. I will have had 60 come next year. I don’t have much time left. I have to figure out what the next step is, and try to figure out how this scales, how to get this message out there, and how to teach others.

Dr. Casey Means: You have a lot of Thanksgivings left, because you literally wrote the book on longevity and are clearly crushing it. I love that way of thinking. When you have an epiphany like you have, there is that sense of urgency of, “How much impact can I make during my time here, to hopefully let others reap the benefits of this way of thinking?”

Your writing is so beautiful. Your blog has been such a great resource, and I recommend everyone check it out—and your book, of course. To me, that feels like one of the really big ways to make a lasting impact.

More Years, Better Years: a Simple Approach to Longevity

Dr. Casey Means: Let’s shift gears and talk about longevity a little bit. It’s interesting how your career has evolved. How do you see the relationship between the worlds you come from—orthopedics, musculoskeletal health—and the concept of longevity?

Dr. Howard Luks: Absolutely. First off, orthopedists are in a fantastic position to identify folks who could benefit from this advice. We’re seeing patients when they may just have some joint pain, but other disease states really aren’t escalating out of control. We can have an impact on them if we can paint a picture of where things are going.

I understand the process of sarcopenia—loss of muscle mass, loss of muscle strength—which is going to dramatically increase the risk of falls and injuries from falls, as well as decrease the ability to recover from falls, and increase the risk of frailty. You don’t have to plan on being hunched over a walker at the age of 75. You can be different.

I’m in a unique position to be able to discuss this with people. When you see an orthopedist, it’s easy to discuss muscles, bones, joints, and therefore function and how function affects longevity and how longevity and healthspan affect function. Not only do you want to live more years, you want more quality in those years. You want to remain cognitively intact.

We can’t forget that maybe half of dementia cases are due to insulin resistance: it’s Type 3 diabetes. We want to be functionally independent. We don’t want someone to pull the chair out, or hold the door open. I have a scribe in the office, and they always say, “Why do you not help these older people into the bed?” They don’t want me to.

You don’t have to plan on being hunched over a walker at the age of 75. You can be different.

We watch how people get out of the chair. Do they have to lurch forward, or can they just stand up? Do they have a little bit of a shake? Are they catching their foot on the ground? There’s a lot to be seen and gathered by just closely watching people. I try to turn this into practical, actionable, simple, useful advice.

At a fairly young age, some people really get it, especially if they’re seeing their parents degrade. It starts to make sense, and you can really hammer home the message that this approach to longevity and improved healthspan is really important. Again, if I see that lightbulb moment, if I see them sit up, and they’re interested, I’ll push. If I don’t, I’m not going to push it.

I’m in a great position to be able to start this process, to wake them up to the concept of healthspan, healthy aging, and staying and remaining active. I love the thing that Peter Attia talks about, the Octogenarian Decathlon. That’s how I’ve worked out my whole life. I have these weight bags, I push them up, I do this, I lift rocks over my head and throw them—complex movements.

I just want to be able to do these things until I’m 80. I don’t want to have to stop. I’m exercising now to be able to accomplish things I want to do when I’m 80 and beyond. You want to make your terminal decade a lot more pleasurable, with a lot less chronic disease burden.

I just want to be able to do these things until I’m 80. I don’t want to have to stop. I’m exercising now to be able to accomplish things I want to do when I’m 80 and beyond.

Dr. Casey Means: I love the concept of compression of morbidity. We’ve almost forgotten that you should live with full function your entire life, and then basically drop dead and maybe die in your sleep, but you’ve been living independently and thriving. You’re mentally sharp. That is my dream. It should be our dream. I want to live a very functional life, and then drop dead, hopefully at an old age. Now, of course, it’s the opposite of that. From fetal life, we are now dealing with sub-cellular pathology of chronic disease and insulin resistance.

I love this concept you talk about, healthspan. Do you think that, with the right way of living, the vast majority of people can compress morbidity, and can live a very long and functional life?

Dr. Howard Luks: That’s the key right there. I don’t promise people years, I promise them good years. If I’m dealing with someone who’s had four or five decades of really bad habits, it’s going to be hard to reverse all the downstream effects of that. But if we get them weight training, we get them strong, we fix their balance, we fix their metabolic health so things don’t worsen, then we can affect significant change, and we will see a far better terminal decade. I’m not buying into the current trends that we’re going to cure aging and live to 130. I’m not there yet.

Dr. Casey Means: A lot of people lean on this idea that it’s bad luck, and that’s the way it is. But if from a young age we are doing the habits you talk about, most likely we’re not going to out of the blue get decrepit and sick. You make the investments, and they tend to pay off.

I’d love for you to walk through this plan you present in the book. What are the simple and actionable strategies that have the most yield in terms of maximizing our longevity?

Dr. Howard Luks: It’s really simple. I like people to create a caloric deficit. Obviously, if you’re a heavy trainer, if you’re an avid runner—you’re running 50 miles a week—no. You have to feed your need. Otherwise, we have an issue with caloric excess.

Why can dieting be successful? Because it creates a caloric deficit. Why does intermittent fasting and time-restricted feeding work? Probably because it creates a caloric deficit. Why does keto work? Because in some people, it helps create a caloric deficit. That’s the mainstay of maintaining a healthy weight.

I know you’re a fan, sleep. We optimize our lifestyle for eating well. We might drink less, we might say, “Oh, I’ve got to walk for an hour today.” Why the hell aren’t you going to bed at 10 o’clock? We need seven to eight hours of sleep. There are zero biological processes that do not suffer from a lack of sleep. You increase your insulin resistance, you get further cognitive decline. You’re just not sharp.

You’re not reactive if you don’t sleep. Our body wants consistency. It’s not going to be as happy if you go to sleep at 10 o’clock this night, then 12 o’clock another night. ‘m not saying you do this every night. I’m saying try. The more you keep a schedule, the better. You need to wake up in the morning, go look at the sun for three minutes—no sunglasses. We’ve got to set a biological clock. We have to give ourselves the best possible chance for success. If you’re going to counteract or go against biology, you have a higher chance of losing that battle. Getting sleep and having a good wake-up routine is super important.

I just tell people to eat real food. I went through a vegetarian phase. I went through a keto phase. I wanted to see what it was all about. My cholesterol went to about 400. I stopped that. Get your protein needs, get your vegetables. Fiber, fiber, fiber, fiber. Oh, my God: how good is fiber for us? You cannot imagine the importance of a healthy GI system. You make more dopamine and serotonin, the hormones that make you feel better, in your gut than you do in your brain. You will make more serotonin and dopamine in your gut, and as a result of exercise, than you will from taking that little pill. What helps feed that gut and nourish it? Fiber. It’s not just to bulk your stools and give you great poops. It actually does something. The bacteria digest it. All the different fibers turn into short-chain fatty acids. Those short-chain fatty acids all have tremendous effects on our body.

I like people to move. Here’s where we can overcomplicate things, especially on Twitter: you have to do HIIT training, you have to do an assault bike, you have to… No, you need to move. We just need to move.

We can’t escape the fact that all-cause mortality improves with walking as little as 6,000 to 8,000 steps a day. There’s no magic in the 10,000 steps. Some papers show that it continues to improve up to 10,000 to 12,000 steps. Some will show that it tends to peter out. There’s probably not a reverse J curve effect on mortality, meaning that you can do too much, unless you’re an ultrarunner and really pushing the extremes.

If you are the type of person who has a sedentary job, running five miles in the morning and then sitting all day is not how you accomplish being active. Your body will derive far more benefit from a little bit of activity throughout the day than it will from being active for a longer time or pushing harder in the morning and then being sedentary.

We need to activate our muscles, and it doesn’t have to be a lot. Stand up from your desk, do five chair squats. Walk to go pick up the copies in the copy machine. Go climb a stairway or two. Make your day a little harder. Don’t park in the spot that’s closest to work. Park further away. Just make it a point to get those extra steps in, because walking throughout the day is super important.

I’ve worn a CGM many times. I wear them for two-week blocks, and it’s really fascinating. I’ve done experiments, whether it’s with a banana or soda or something else, and I’ll sit there one night. I’ll just eat this, and I’ll see what my glucose response is. Then the next day I’ll eat the same thing, and I’ll go for a walk. Nothing complicated. I’ll go for a walk. Inevitably, the glucose variability and the response is blunted. Even simple walks are going to improve your overall health and wellbeing.

It’s not just your muscle activation, and it’s not just your glucose response. I like to tell people to push and pull heavy things. This is really important. Sarcopenia should be a four-letter word, because it sucks. It is age-programmed loss of muscle mass. Starting at the age of 35 to 40 we lose approximately 0.8 to 1% of our muscle mass per year.

That will correspond to a significant loss of muscle strength. It’s going to accelerate in your mid- to late 50s, into your 60s, and beyond. You cannot reverse sarcopenia. Once those muscle cells are gone, they’re gone. You can mitigate its decline, and you can build muscle mass. I tell people to push and pull heavy things. We need to do resistance exercise, and we need to do legs.

When we were young, we did chest and arms. Forget that. We need to do legs. Yes, you can do the chest and arms, too. I’m not against it. But your legs are your biggest muscles. Training these muscles will derive the biggest metabolic effect and strength improvement. You’re going to get up from a chair, you’re going to breeze through movements. You’re going to ease your way upstairs. You’re going to be less tired, less fatigued, more fall-resistant, more fall-resilient. You’re going to improve your recovery. The more muscle you put in your muscle bank at a younger age, the more you get to withdraw when you’re older. It is really hard to build new muscle. It is really easy to maintain muscle mass. That means we need to prioritize leg strength, and core strength for our balance.

We need to maintain that muscle mass throughout our middle decades in preparation for our later decades, if we want to remain active. This does not mean that a 70- or 80-year-old should not start lifting weights, because an 85-year-old, after one resistance exercise session, is going to build new muscle protein. They should be active in pushing weights, too. My parents, who are in their 80s, hate me because I have them working with trainers. They remark about how much better they feel, how much easier it is to move around. Push and pull heavy things.

And now, really important: socialize. Have a sense of purpose. What gets you out of bed in the morning? Call that friend. Don’t text them. Try to build your social network. You don’t have to have a million friends. Have two or three whom you can really rely on, whom you really treasure listening to and talking to, whom you can go out with, go hiking with, go running with. You’ll be far better off in the end if you build and maintain those relationships than if you don’t.

The more muscle you put in your muscle bank at a younger age, the more you get to withdraw when you’re older. It is really hard to build new muscle. It is really easy to maintain muscle mass. That means we need to prioritize leg strength, and core strength for our balance.

Dr. Casey Means: Those are such beautiful pillars of longevity. I love the way you frame them because they are simple but profound. It’s not like you need to do 30 minutes of high intensity interval training per day, and then you need to do this exact type of resistance training. Push and pull heavy things. Move your body. Eat real food. It’s the basics.

Stress, Longevity, Current Therapies, and the Future

Dr. Casey Means: Especially in the world we’re living in, where over 90% of people are not even eating the recommended dose of fiber per day, and over 75% of people aren’t getting the recommended amount of exercise per day, the margins are definitely important for people who are hyper optimizing. These are the key pillars to focus on.

How do you think about stress, trauma, and psychological wellbeing? This probably fits into sense of purpose and socialization, but how does hyper-vigilance or stress affect health? Does it play a role?

Dr. Howard Luks: It does, especially in the orthopedic space. The hypervigilant—the hyper stressed—will tend to narrowly focus on one problem and the effect that problem is having on them. When I was a trauma surgeon, it was very clear. We had these two opposing groups. We would see people with multiple fractures. You spend all night fixing them, you see them once or twice, and they say, “I’m out of here. I have things to do.”

Then you see the others—hypervigilant, a little stressed—and they require a lot more attention. Five or 10 years later, they’re still your patients. It does have a role. This is an important group to recognize. It’s important to help them find outlets that help them de-stress, emphasizing that this is not such a big deal, that this is not going to require an operation. Your life is not over. But it’s the whole package. If we’re hypervigilant, if we’re overtraining, if we’re in the top 3%, we can’t just choose one or two of these things.

Dr. Casey Means: It’s such a good roadmap. I how you position it in a way that really feels accessible. You talked about fiber, and clearly you have a passion for fiber and real food. Do we have any understanding about how the microbiome affects our outcomes musculoskeletally or orthopedically speaking? Is that something that’s been studied at all?

Dr. Howard Luks: I’ve communicated with a few microbiome scientists over the last year. There are interactions. They are not well-studied. They’re seeing in the blood sugar space pronounced effects with certain bugs in your colon. As the data become more precise and more elaborate and better structured, we’re likely going to see a very clear relationship. We’d be too narrowly focused to think it’s not going to have an effect. Again, why would short-chain fatty acids not affect all tissues? They affect your happiness, your anxiety levels. That is going to affect the level of pain you’re going to have. It is going to be connected in some way. Is it directly connected? Is it causing a change within our joint structure? I don’t know. I hope it is.

Dr. Casey Means: You have a section of the book called “Why You Don’t Need to Be Concerned About Osteoarthritis.” I even have a little fear about it, because the surgeon looked at me and said, “If we don’t do this surgery, you’re going to have osteoarthritis,” which I’m not buying into because I feel amazing now and I believe in the regenerative capability of my body. I’m trying to shut out that negativity. But why should people not be concerned about osteoarthritis?

Dr. Howard Luks: There are varying degrees of how osteoarthritis will affect you. If you’ve been suffering from it for 40 years and you’re crippled, we’re certainly going to help you, probably with an operation. However, more commonly, you have a mild joint ache. Your shoulder hurts when you play tennis, it hurts when you kneel down, when you’re gardening, when you’re out hiking. And you’re a little worried.

You may talk to your doctor, and they may say, “Stop that. Don’t be active.” We focus on the fact that the etiology of osteoarthritis is, more often than not, biological. That cartilage nutrition and health is based upon this repetitive loading. It likes the repetitive loading. There’s no reason to stop being active. As we also discussed, we had runners who were less commonly resorting to knee replacements as opposed to non-runners with the same degree of arthritis.

We have to do away with the thought that osteoarthritis is a death sentence, or a terminal disease. It’s not. In some of you, it’s reached the point where yes, you have no other options available. Surgery can be very beneficial for you—life-altering. But for the vast majority of people, that’s not the case. If you can play two sets of tennis instead of three before you get sore, do it. If you can run two miles instead of four miles or if you have to fast-hike or fast-walk instead of run, you’re going to do that.

You’re not going to destroy your joints by staying active. Weight training is not going to destroy your joints. If the pain is mostly in the front of your knee, weight training is going to alleviate the pain, in the vast majority of circumstances. It’s not the end of your life. It’s not the end of your joint. The more active you stay, the happier your knee is going to be. The stronger you keep your leg, the longer you’ll keep your knee. That same goes for shoulders.

Dr. Casey Means: Such a hopeful message. What are your thoughts on some of the regenerative therapies happening in orthopedics, like PRP or stem cells being injected into joints?

Dr. Howard Luks: It’s a complex topic. Today, the issue with stem cells is you have to try and tell them what to do. You can’t just inject a cell, you need to inject the instructions. Cells migrate through the body according to these instructions, or these molecules they sort of sense like a mouse that’s following the smell of cheese. If we take stem cells out of your bone marrow, clean them up, and inject them into your knee joint, they’re going to sit there and look around at each other: “What the hell am I supposed to do now?” We haven’t figured out how to stick in the molecule directions that says, “Hey, go form cartilage or go form a meniscus or go form a ligament.”

Sometimes, by injecting them in the ligament, you’ll get some factors and chemicals from the ligament itself. But cartilage has been a very challenging tissue for us to regrow. We’ve been studying this for four decades, and we’re just not there.

Now people who get stem cell injections or PRP injections—and it’s really bone marrow aspirate I’m talking about—can derive pain relief from an injection. That pain relief can last eight, 10, 12, 14 months. It is not regenerating anything. You’re not growing cartilage. You’re not decreasing the chance you may need a knee replacement in the future. You shouldn’t pay $10,000 for it.

It’s a similar case with PRP. There are studies and papers that show everything, but unfortunately, there are many different PRP systems out there. A lot of doctors don’t want to pay for systems. They’ll spin it down in their own centrifuge. Some will take it really seriously and they’ll spin it in a specific system for a specific time. They’ll actually document how many platelets are in that injection. They’ll place it properly. You can feel better again after having had an arthritic knee, or after having had various types of tendon pain. You might feel better after those injections. It may help with tendinopathy. It may help with tendon regeneration. If we’re putting stem cells into a tendon, we have those chemicals that will serve as that message to say, “Hey, make a tendon,” as opposed to being inside a joint, where they really don’t know what to do. The future is really bright. I don’t know when that future is going to arrive, because we have a long way to go before we figure out how we can message these cells.

Dr. Casey Means: That’s really helpful. You could go to the websites of the people doing platelet-rich plasma or stem cells and it kind of looks like the panacea. But we can inject some cells, but they need the instructions, too. We haven’t quite figured out exactly how to get them to do what we want. That’s fascinating.

As a surgeon but also someone who has been focusing on the more biological aspects of health, you’re very much in the structural world of health. Do you think there are a lot of surgeries in your field that could be avoided or prevented by people just optimizing their underlying biology and metabolic health?

Dr. Howard Luks: Yes. I can’t tell you how many people I see for a new problem every week who say, “Hey, I saw you 10 years ago. You were my third opinion. You said stay out of the operating room. I did. I did great. Now why does my shoulder hurt?”

Nothing gets better in six weeks. Let’s say your knee hurts and you’re a runner or you’re working out and you happen to get an MRI and it shows a meniscus tear. Most runners my age have these degenerative posterior horn medial meniscus tears—loose pieces. As I often say, injury can arise by taking out those pieces if they’re not actually bothering the knee. There’s a good chance that it may not be what’s bothering the knee. Sometimes we’ll see a capitis or an inflammation of the tissue around the meniscus, because maybe it’s shifted a little.

If you wait long enough, the majority of you are not going to need an operation for this. There have been placebo-controlled, randomized trials of people who had degenerative posterior horn medial meniscus tears. In one study, one group went to sleep and had the operation. One group went to sleep and had two incisions placed but didn’t have the operation. They both got better. They’ve put them up against physical therapy and surgery. They both get better. There’s a lot at play here. Is it a placebo effect? Is it an intervention effect? A lot of orthopedic procedures up against placebo don’t fare well.

The bottom line is that there are many findings on MRIs where it’s easy to convince someone you need an operation. Many times you don’t. A lot of my friends and I will talk about this, especially the older ones, because we are getting wiser. You’ll see people in the office with shoulder pain and say, “Look, you’ve got this tiny little tear, a little bit of inflammation. With some anti-inflammatories and a few months of physical therapy, you should be fine.”

They go to therapy for three weeks. They hate it. They still have pain. They want an operation. They really shouldn’t have it, but they choose to have it. They go forward with it, and after four months of physical therapy, they feel great. They say, “See? I needed the operation.” No, you needed the four months of physical therapy.

You have to realize that very few things get better in six weeks. David Ring, a hand surgeon out of UT Austin, wrote a great article about tennis elbow. You’re all going to get it. It’s going to go away for 99% of you. And if it doesn’t, there’s something else wrong. Some people are really bothered by it. We know that steroid injections will often make it worse. It’ll change the tendinopathy and harm the tendon. Those are situations where you can try PRP injections and other interventions. But they did a randomized trial of surgery, the formal procedure versus just making an incision and not doing anything to the tendon, and both groups got better. Was it a denervation effect? Was it a placebo response? We don’t know.

Many times, if given enough time, problems will resolve. Sometimes they don’t. I am a surgeon. I operate every week. There are things that do require surgery. Oftentimes, that’ll be up to you. Again, this is not life-or-death medicine, and we are more likely than not operating on too many things. As we get older, things show up on our MRI. It’s very easy to take an MRI report and say, “Look at all these things that are wrong. I can fix them for you.”

If you come into the office, because something hurts, it’s going to take me longer to convince you that an MRI or surgery is not necessary than it is to advise, “Here, sign here and we’ll fix this for you.” It’ll take me longer, and you may not agree with me, and you may be more unhappy because I said you don’t need an operation. That happens. I’m not always correct, and you may run somewhere else and have a different opinion and have a surgery and do wonderfully. Great. I am human. But I do think they’re operating on too many people.

Dr. Casey Means: One of the things I’m taking from what you just said is that part of the equation in facing physical challenges like this is actually tapping into patience and healthy coping. We are an instant gratification culture. In a sense, surgery feeds into both consumerism and instant gratification. We get something. It’s of high value. But it’s not of high value. It’s actually the opposite of high value. It’s a very high cost for possibly not a great outcome.

We have difficulty sitting with discomfort. Our general western culture has conditioned us to think discomfort is a bad thing rather than a growth opportunity. A lot of this probably does come down to mindset. We also carry this misconception of the body as something there to decay and hurt you and cause problems, as opposed to a dynamic flowing entity capable of regenerating.

It gets down to a lot of fundamental framing issues and modern culture things we struggle with in the western world—impatience, consumerism, and lack of trust in the body. I love everything you said. There’s a lot of wisdom there.

I had an opportunity on a silver platter to have this knee surgery. My insurance would’ve paid for it. I would’ve felt like I did something. That could’ve made me feel good about “taking charge of my health” or doing what the doctor recommended.

Instead, I had to sit with a little bit of pain for an unknown period of time. This could last six weeks. This could last four months. I had no idea, but I trusted my body. Also, the clicking—was it ever going to go away if I have surgery? I’m pretty sure the clicking would have gone away because the cartilage would be shaved off, but it might never go away.

I had to kind of use that as a mindfulness exercise: there’s no rush and I trust that my body can handle this. And I did what you recommended in your book, which was focus on what I can do: eat a real-food, anti-inflammatory diet, eat lots of fiber, move my body, start doing resistance training, focus on the things in my life that are good and purposeful.

And voilà, four months later, of course, it’s better. That’s not going to be the case for everyone. But there’s a whole mindset thing here that is important for the American patient to think about and hear about, because a lot of it comes down to us and our ability to cope with uncertainty and have patience.

Dr. Howard Luks: We have redundancy, we have capacity, and we have reserve. We get by just fine. We are not going to look the same on the inside as we did when we were 20. We don’t look the same on the outside. I shouldn’t expect it to be on the inside. I’m wrinkled outside. I’m wrinkled inside, too. It’s okay.

Dr. Casey Means: You are a huge inspiration to me. I’m so grateful for how you are trailblazing in the field of metabolic health, orthopedics—many different areas. You’re spreading your word on Twitter. I am just grateful you exist, Dr. Luks, and thank you so much for being here. Let people know how they can find you on the internet and connect with you.

Dr. Howard Luks: Number one is Twitter. It’s my only place in the social world, and my website, howardluxmd.com. It has my email there. If you don’t abuse it, feel free to send me a message.

Dr. Casey Means: Anything we missed today that you want to make sure to get across to the listeners?

Dr. Howard Luks: There’s always more to say. Don’t overthink this. If you’re the average person out there who hates exercise, who thinks of exercise as work, but you’re concerned about your health, you don’t need an assault bike, you don’t need a Peloton. You don’t need to overthink this. You need to eat well. You need to go outside. You need to make your day a little harder. You need to sleep better. Try not to stress eat as much. Try to find that little win. It matters, and it works in the end. If you’re an overachiever, great. So am I. Every now and then, we’re going to have an injury, and that’s why I’m here, too.