Dr. Casey Means: Dr. Sara Gottfried is a physician-scientist who graduated from Harvard Medical School and MIT, and completed her residency at UCSF. She also completed a two-year fellowship in advanced cardiometabolic health at the Metabolic Medical Institute, and is the director of precision medicine at the Marcus Institute of Integrative Health at Thomas Jefferson University, where she’s on faculty. Over the past 20 years, she has seen more than 25,000 patients, and specializes in identifying the underlying cause of her patient’s condition to achieve lasting health transformation, not just symptom management.

I could not be more excited to welcome Dr. Sara Gottfried back. Last year, we had an amazing conversation about understanding predictive markers of metabolic dysfunction, and today, we are going to be diving into a topic that is personal to both of us: women’s health. She just published an incredible paper about this topic called “Women, Diet, Cardiometabolic Health and Functional Medicine.”

For nearly every patient, she designs an N-of-1 trial to provide rapid information on whether the personalized plan is improving outcomes. She has four New York Times bestselling books, including The Hormone Cure, The Hormone Reset Diet, and Younger. Her newest book, Women, Food and Hormones, is incredible. These are some of my favorite books, all of which have profoundly influenced me. I’m so excited to get to chat with her.

Metabolism, Myths, and Getting to the Root Cause

Dr. Casey Means: I’d like to start with the big picture. Why should women especially care about their metabolic health? I think this is important for both women and men to understand and share with the women in their lives.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: There are a lot of reasons why women should care about metabolic health. The first is that women are more vulnerable than men. A lot of folks have this misunderstanding that men die more of cardiometabolic health, and it’s just not true. In some ways, men keep getting better, and those benefits are not equally applied.

The second reason is that what you measure improves. I don’t want women or men to outsource metabolic health to their physicians or healthcare professionals, because the more you can take it on yourself—that’s what really makes the difference in terms of improvement and preventing some of those riskier, scarier diagnoses.

When metabolic health declines, it’s mostly silent; you don’t know about it. You don’t know that, under the hood, as your glucose is creeping up, insulin, maybe a decade before, was starting to creep up. You may notice a little more belly fat, but there’s this change that occurs, sometimes up to ten to 15 years before you get a diagnosis, or someone tells you, “Okay, your fats and glucose now put you in the pre-diabetes category.” It’s mostly silent, which means that you’ve got to focus on it.

Many of these changes start around age 35. What’s up with that? Women have these really precipitous changes with their sex hormones. After 35, the balance between estrogen and progesterone changes. That’s where you notice this significant turn in terms of cardiometabolic health.

Of course, insulin gets involved. As you lose metabolic health, you lose aliveness. Out of all of these reasons, that’s the one to care most about. I imagine you also want to be as alive as possible as you get older. Don’t let something that’s so preventable rob you of that sense of delight, and keep you from living your fullest life.

Dr. Casey Means: At the end of the day, what could be more important than that spark inside of us, that sense of aliveness?

Can you paint a picture of how “cardio” and “metabolic” link together, and how that feeds into so many other aspects of our life and our health?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: We met at a functional medicine conference, and in functional medicine, we really believe in looking at root causes. In the system you and I trained in, there are all these silos of care. If you’ve got a heart problem, you go to the cardiologist. If you’ve got a problem with your insulin, and you’ve got a diabetes diagnosis, you go to the endocrinologist. If you’ve got gut issues, you go to the gastroenterologist.

But this doesn’t work. Frankly, our healthcare system is broken. In functional medicine, we look upstream. We don’t use those silos of care. We look at systemic imbalances that lead to problems such as heart disease.

You don’t just suddenly have a heart attack at age 65. This has silently been happening in the background for decades. The more we can address that years and years before the scary diagnosis, the better off we’re going to be, because that’s when we can really intervene. That’s when we have the best chance of reversing some of these processes.

The reason I lump “cardio” and “metabolic” together into cardiometabolic health is because the root cause for cardiovascular disease and metabolic disease are the same. It doesn’t make sense, in my mind, to separate them.

Cardiometabolic conditions are interrelated, interdependent conditions that affect things like the heart, the cardiovascular system, your blood vessels, and your metabolism. It’s important to realize that the kinds of outcomes we’re talking about—heart attack, coronary heart disease, insulin resistance, prediabetes, diabetes, high blood pressure—are all linked together. Often, one of the common themes is insulin resistance, where your cells become numb to the insulin signal. That’s why I like to group these together.

We need to bust a couple myths here. One myth is that your metabolism is how fast or slow you burn calories. It’s so much broader than that. Metabolism is the sum total of all of the biochemical reactions in your body. The more you view it that way, you realize that aliveness—waking up in the morning with vitality and vibrancy, loving the work you’re doing—depends on metabolism. It depends on these biochemical messages and signals in the body, and having these signals work on your side.

When they start to falter, which is really the default in our country—88% of Americans are metabolically unhealthy—and the default is that you start to lose your metabolic health, you’ve got to turn it around so that you can really access that vitality.

Dr. Casey Means: I love that framing. Metabolism is not just how quickly we burn calories. It’s literally the sum total of every single chemical reaction happening. That is complex, and it takes a holistic framework to both assess what might be making metabolism go off the rails in a particular patient, and what interventions might need to be incorporated to improve the metabolism.

I always think it’s funny when people talk about how just going low-carb could fix metabolism. When you’re thinking about metabolism as a complex set of chemical reactions, just removing one macronutrient is never going to be the answer. It’s really about building a metabolically healthy body that can do all these things.

Metabolism is the sum total of all of the biochemical reactions in your body. The more you view it that way, you realize that aliveness—waking up in the morning with vitality and vibrancy, loving the work you’re doing—depends on metabolism.

Women’s Unique Vulnerability to Cardiometabolic Disease

Dr. Casey Means: You mentioned that women are much more vulnerable than we think to cardiometabolic disease, even more so than men, and for unique reasons. Can you walk us through a little bit of understanding what that increased risk is for women? What are some of the stats that women need to know about cardiometabolic health?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: The stats are alarming. In developed countries, half of women will die of mostly preventable cardiometabolic disease. How is that possible, especially since so much of it is preventable? In the United States, every 80 seconds, a woman dies of cardiometabolic disease. Cardiovascular disease is the number-one cause of death. But if you look at the top five, most of them are related to cardiometabolic health. That includes coronary heart disease. It includes having a heart attack. It includes stroke, diabetes, and insulin resistance.

When we look at some of the differential effects, why are women more vulnerable? We know that for women who have non-insulin-dependent diabetes, their risk of mortality is quite a bit higher than it is in men. They start to show vulnerability with much lower glucose levels. For instance, a woman with a fasting glucose level of about 110 milligrams per deciliter is going to have vascular damage. For a man, it takes a level of around 125, 126 milligrams per deciliter before we start to see that vascular damage.

Another differential effect is what’s known as type 3 diabetes, and that is Alzheimer’s disease. Two thirds of cases of people with Alzheimer’s disease are women. We think some of that risk is related to hormonal changes. Women suffer from autoimmune disease at a much higher rate than men. In general, women have a more responsive immune system, which can work in your favor when you get pregnant, or in terms of vaccine response. But it can also backfire. That over-responsiveness is a way to frame autoimmune disease. Some people even think that cardiovascular disease is an autoimmune disease.

Throughout my career, I’ve known about the increased risk that women have compared to men. We’ve known this for 30 years, but awareness is actually declining. In 2009, for instance, when they asked women about the leading cause of death, about 65% of them said, “Oh, it’s cardiovascular disease.” More recently, in 2019, only 44% of women knew that cardiovascular disease was the leading cause of death. Even with the Go Red For Women campaign that we’ve had—even with all of this public awareness—awareness among women has declined.

This also was so upsetting when I read it: For a woman having a heart attack who goes to the emergency room, if she sees a female physician, her chance of survival is two to three times higher than if she sees a male physician. I’m not throwing male physicians under the bus. What this speaks to is the female-specific awareness that female physicians seem to have.

It’s something we’ve got to change with male physicians. You might ask, “Well, what about if you’re a guy and you’re having a heart attack?” The survival was the same, whether they saw a male physician or a female physician. That speaks not to a sex difference, like smaller coronary arteries or this differential effect of glucose, but to a gender difference, which is socially constructed.

Dr. Casey Means: That is just absolutely harrowing. In your paper, you mention that women experiencing a heart attack can present different symptoms than men experiencing one. Could you run through what a woman might experience during a heart attack compared to the traditional signs and symptoms of left-sided chest pain and radiating arm pain? How might a woman present?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: There’s a reason why women have different symptoms than men. We all learned that a man who’s having a heart attack has the classic symptoms you just described. It feels like an elephant is sitting on their chest; they get severe substernal chest pain, right underneath the bones of the chest, that radiates to the arm. That’s what men experience, because they’re much more likely to have obstruction of their coronary arteries. Women are different in the sense that they’re more likely to have erosion of a clot inside the coronary arteries. They’ve got smaller coronary arteries, but more microvascular damage, so their symptoms are more subtle.

Instead of feeling like an elephant is standing on our chest, it feels more like neck pain, nausea, or shortness of breath. That’s the classic way that it presents: nausea, vomiting. I had one patient who presented with syncope: She passed out. That was the only symptom of an acute myocardial infarction, a heart attack, she had. We’ve got to be aware of these subtle differences. For women, they’re much more atypical. They’re not the classic symptoms we all learned, as they are for men.

Dr. Casey Means: Why aren’t we learning the differences in symptoms for women versus men in medical school? This feels like just the tip of the iceberg. There are so many different conditions for which men and women might present differently, and for which we might only learn the male category. What is leading to that?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: There’s a confluence of factors. The first is research bias. Women were not routinely included in research until the 90s. That’s shocking to me, but it’s true. Until pretty recently, it was assumed that the experience of men, and what was found in research studies, also applied to women.

The other issue is patriarchal society. Women’s lives are not valued as much as men’s. There’s less research money, less of an interest in looking at sex and gender differences. The funding often goes to these pharmaceutical companies to do randomized trials with the latest drug. Once that drug gets approved, it goes into the guidelines. The guidelines don’t always consider some of these differential effects.

There was a recent trial looking at blood pressure control. They found that blood pressure at a lower level conferred greater risk. That led to some changes in the blood pressure parameters we like to look at. That increased risk was shown across the board in men and women. It was significant in men. It was not significant in women. That’s an example of some of the bias that comes through. And yet the guidelines apply blanket statements intended for both men and women.

For a woman having a heart attack who goes to the emergency room, if she sees a female physician, her chance of survival is two to three times higher than if she sees a male physician.

Then, there’s just a lack of awareness about some of these biological underpinnings. I mentioned that women have smaller coronary arteries, and are therefore less likely to have obstructed disease. They’re more likely to have microvascular damage. The kind of diagnostic tests, like angiograms, just don’t have the same sensitivity and specificity in women compared to men. There are differences in the way that guidelines are used.

Women are less likely to receive guideline-based treatment, and we’ve already talked about some of the reasons why guideline-based treatment might be limited. Another difference is that women have more abnormal coronary artery reactivity. You may see changes that are not persistent. Men are more likely to have a plaque in a coronary artery and have an obstruction. Women are more likely to erode a clot on top of the plaque. It’s that erosion that leads to these more subtle symptoms compared to men.

Dr. Casey Means: That’s fascinating to think we might actually need to differently approach how you assess a female patient versus a male patient. Differential risk factors were such an important part of the paper. Women are having, in many ways, a different experience of life, culturally and biologically.

How Body, Mind, and Culture Converge

Dr. Casey Means: These things can feed into our risk for disease. What is happening in a woman’s life that can predispose her to a higher risk for cardiometabolic disease?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: There are a lot of them. My next book is about trauma and how it shows up for both men and women in ways that are not just psychological. Trauma affects the immune system, the neurological system, and the endocrine system. We think of the psycho-immuno-neuroendocrine system as the PINE network.

Adverse childhood experiences, ACEs, are higher in women compared to men. It leads to this activation of the PINE network—of the psycho-immuno-neuroendocrine system—as well as psychological changes that can then impact cardiometabolic health. You’ve got that, on top of this difference in physiology we’ve talked about: a lower glucose threshold in terms of oxidative stress and damage to blood vessels; risk of vision problems, including retinopathy, and problems with the retina; and kidney problems.

There’s also the hormonal network. The change in estrogen that occurs in women over the age of 35 is sudden and steep. On average, estrogen production in women starts to decline around age 43. That’s where some women have symptoms. They’ll have hot flashes and night sweats; maybe their PMS gets worse, or their periods get closer together. They might become heavier. They might be lighter. They might alternate, and they never really know what they’re going to have.

They can also have some brain changes: They might have some memory issues. They might have more moodiness, or depression and anxiety. All of those relate to your risk of cardiometabolic disease. When I was first taught about hot flashes and night sweats, I was taught to medicate them away with hormone therapy, in those considered good candidates. Now, we know that those symptoms are biomarkers of greater cardiovascular risk, and potentially greater cardiometabolic risk.

There’s less data about metabolism in those folks, but it certainly changes the way that glucose is used in the brain. Starting in their 40s, glucose metabolism starts to decline for about 80% of women. We can see this with PET scans, where you track what happens with glucose in the brain.

Women have this thing called cerebral hypometabolism, where they just don’t use glucose the way they once did. It’s associated with many of these symptoms, and we think it might be an early phenotype of what develops later into Alzheimer’s disease. Your brain slows down. You’re not on top of your game like you used to be. You can’t multitask. You have to write things down more often. Those are really common symptoms.

And, women have a significantly higher rate of insomnia as men do. But when you look at the data on insomnia, there’s so much you can do in a woman in the age group of 35 to 50 to help prevent her from falling down those hormonal stairs. One night of bad sleep is associated with changes in your insulin and in your cortisol. You can imagine how, if you group together months and then years of poor sleep, that can impact your metabolic health. I’m in the camp of intervening and using hormone therapy in those folks as soon as possible. I try herbal therapies first, but I have a low threshold for using hormones in those women.

Another huge difference is stress. Women have higher perceived stress compared to men, and the way that they experience stress can be translated into cardiometabolic function. It’s much more sensitive and delicate than it is in men.

Another issue is pregnancy. I think of pregnancy as a stress test, one that I failed when I was in my 30s. I did one of those Glucola drink tests, where you drink glucose and then measure your blood glucose an hour later. The cutoff is 135 milligrams per deciliter for your glucose. I was at 134, and I remember my OB/GYN saying, “Oh, don’t worry about it, Sara. Just stop drinking juice.” Well, I wish I had a continuous glucose monitor at that time, because I was showing early signs of insulin resistance, and no one was thinking about it. I’m a physician, and I wasn’t thinking about it. We want to be thinking of pregnancy as a stress test. We want to pay attention if you have problems with your blood pressure, whether that’s chronic high blood pressure or pregnancy-induced hypertension or preeclampsia.

If you have problems with gestational diabetes, or prediabetes, like I did; if you have a small gestational-age baby; if you have problems with an abruption—these are some indicators of atypical risk factors for cardiometabolic disease. I see so many patients who’ve had preeclampsia during their pregnancies. I always ask about what happened during their pregnancy, because we know that preeclampsia doubles the risk of future heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. It gives you a fourfold increased risk of future high blood pressure or hypertension. There’s this window of opportunity for these folks, basically until about age 50 to 55, where we want to turn this ship around. Pregnancy is such an important test of cardiometabolic function.

Another factor that is important to consider is birth control pills, which increase your risk of cardiovascular disease. We know that it changes the way you respond to stress. The control system for your hormones, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) access, becomes more rigid. It just doesn’t roll with the punches quite the way it used to. It also affects the microbiome.

There was a study from England showing that women receive 67% more antibiotic prescriptions than men. That certainly affects the diversity of the microbiome, which can set you up for a range of diseases, including diabetes and autoimmune disease.

We think the reason women receive so many more antibiotics is because of our propensity for bladder infections. We’ve got to be thinking about these sex-based differences, and also about the life course of a woman and some of these differences in vulnerability that give us a window of opportunity to intervene.

Dr. Casey Means: You mentioned several different categories, one being psychosocial and cultural experiences women might face at different rates than men, which translate biochemically into increased metabolic risk. That includes things like adverse childhood experiences, natural inclinations toward how stress is processed, and caregiver burden. Then you’ve got hormonal issues, and not just during menopause, but during childbearing age and pregancy. Lastly, you have things related to medication: oral contraceptives, antibiotics.

These are great for women to hear and understand, because every modifiable risk factor is also an opportunity for intervention and empowerment. These things are often not brought into the conversation around assessment and treatment.

A Better Assessment

Dr. Casey Means: Certainly, we take our standard social history and our medication history when we’re doing our physical for a patient, but it’s cursory at best. Often, it’s not actually incorporated into a treatment plan.

How do we need to move forward, as individual patients and as a medical community, to rethink how we’re assessing patients and how we’re building a plan for them in terms of cardiometabolic disease?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: I love that question. When I was in my 30s, I thought that menopause was this cliff that I would fall off of at 51 or 52; I didn’t have to worry about it until then. A lot of people have this perception that you don’t have to worry about a high blood pressure or having a heart attack until after menopause. But the truth is, rates of hospitalization for heart attack in women ages 35 to 54 are increasing. Why is that? We are becoming more metabolically unhealthy. As you said, there are all these clues. We just have to be able to put them together.

Most physicians are not thinking along these lines. They’re just thinking in terms of their guidelines like, “Well, what’s her LDL? What’s her blood pressure today?” They’re not thinking in terms of, “Oh, something was unasked in that pregnancy,” “She’s struggling with insomnia,” or “She’s got other atypical risk factors like endometriosis or migraine with aura.”

This is where it’s important to bring awareness so that women can partner with their clinicians and start to intervene as soon as possible. This is the work of precision medicine. If I have this lovely woman in front of me telling me she wants to lose 10 pounds, we’re going to instead think, “Okay, what’s going on with her genetics? How is that interacting with her environment? What kind of behaviors are modifying those changes, like what she does with food?” And then, “How do we optimize that gene environment interface so that this woman can live as long and as well as she wants, so that she can have that sense of aliveness?” I think that’s essential.

Dr. Casey Means: You mentioned we’re starting to see hospitalizations for heart attack go up in women as young as 35. What’s especially shocking to me is that this is in the face of increased use of statins, presumably this medication that is going to decrease LDL cholesterol and solve all our problems with heart disease.

Statin use has gone up almost 80% since 2002. Now we’re prescribing about 221 million statin prescriptions per year. And yet heart disease is still the number-one killer in the United States—700,000 people a year die from it. There’s an approach-outcome mismatch we’re seeing.

Much of what makes me obsessed with your work is that you approach things very differently, through a much more multifactorial lens. Can you describe how you assess a patient and build this comprehensive assessment, both from a biomarker and social perspective? How do these feed into your treatment plan?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: I love that question, and I’m glad you led with statins. Statins change your risk of insulin resistance. Let’s go back to the big picture: How do you do this kind of assessment? What are you pulling together? I’ve got a few different resources I use. First, I learned the functional medicine approach. I’ve done all the courses that are offered at the Institute for Functional Medicine.

They’ve got a way of retelling a patient’s story and putting it together so we think about those upstream clinical imbalances. There’s an example of this in the paper, if you want to see how this lays out. When I’m listening to a patient, I’m listening for a few specific things. I start first with what are known as the ATMs: antecedents, triggers, and mediators. Antecedents are things like your genetics, your family history, and your age. I’m especially listening for a family history of cardiometabolic disease. I’m also all over their insulin, glucose, A1C, and uric acid.

Triggers are things that can influence the course of disease. I’m listening for narratives such as, “I felt totally normal until I became pregnant. Then in pregnancy, something happened. Afterwards, I gained all this weight and I couldn’t lose it. My metabolism changed.” And then I’ll say, “Okay, what else happened in pregnancy?” She might tell me, “I was diagnosed. I had this problem with my glucose test, and then I did the three-hour test. But that was okay. They told me not to worry about it.” Then I think, “Ding, ding, ding.” This is the sign of insulin resistance. That woman never gets additional follow up, postpartum. She’s just kind of left to go to pediatrics services, and doesn’t get that metabolism checked again.

Mediators are things that can modify your risk of disease. That can include chronic stress and insulin problems. It can be things like sleep apnea. Whenever I see someone with a fair amount of visceral fat, or their visceral fat is increasing over time, to me that is sleep apnea. It’s so common. It’s not just present in people who are obese, and it’s really easy to test it at home. Now, you can do home testing for sleep apnea.

Then I’m thinking about modifiable lifestyle factors. That’s where I’m asking a patient about things like, “What’s going on with your sleep? Do you track your sleep? What’s happening with deep sleep, with REM sleep? Do you have a lot of interruptions? Have you ever measured your oxygen saturation over the course of the night? What’s going on with your connections, your relationships? What’s happening with stress? Are you at a place of eustress—a normal, healthy amount of stress—or do you have too little, or too much? What’s going on in terms of nutrition?”

In some ways, that’s the thing I care about the most; that’s where I like to start in terms of helping people. I take a pretty thorough nutritional history, and look at exercise and movement. Those are the five categories: sleep, exercise, nutrition, stress and resilience, and relationships.

This whole way of taking a patient’s history involves what are known as the seven clinical imbalances. These are those upstream factors that can lead to different conditions depending on the individual’s genetic vulnerabilities and how they interact with the environment.

The Institute for Functional Medicine uses specific language—which is a little different from the language I like to use, because I just find that patients can understand it better—but I always have their sort of checklist here at my desk because I use it on every single patient. I’ll just rattle through this: Number one is your gastrointestinal system, your gut. Number two is your immune system and inflammatory tone. Number three is environmental inputs. Number four is energy production. Oxidative stress is part of that. Number five is detoxification. Some of us are great at detox, a lot of us are not. Number six is neurotransmitters and hormones. Number seven is structural integrity.

Then, at the core of the matrix is mind, body, emotion, and spirit, which I always like to ask about. It’s important to realize that when you map the matrix on a patient, it gives you a fuller picture of what’s going on than the standard history and physical you and I were taught to do. Another myth a lot of people have when it comes to cardiometabolic health is that, “Well, I eat healthy and I exercise moderately for 150 minutes a week, so I don’t have to worry about my cardiometabolic health.” The truth is, once again, that there’s this whole silent process that’s happening in more than 88% of us, and the sooner you intervene, the better.

I take care of professional athletes. You would think athletes don’t have much to worry about. It seems like they won the genetic lottery, and that their matrix might be empty, but that’s not the case. Often, they’ve got a strong family history of cardiovascular disease. They’ve got a family history of diabetes. I’m really interested in what’s going on in terms of their gut, how that’s talking to the immune system, and what’s happening with their hormones, especially insulin, leptin, and adiponectin. I’m doing this systematic review and meta-analysis right now using CGM data. We know that pro athletes often have much higher blood sugar than we originally thought.

I have a patient who was started on a statin. He really likes to do a kind of quantified-self time series. He does quarterly blood draws to track things like fasting insulin, with a Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR), and glucose. We’re looking at the relationship between the two. We’re also looking at a few other biomarkers that relate to this, like his lipids. His doctor started him on a statin, which was an opportunity to see the before and after. His LDL, the main thing being treated with a statin, improved.

But this was at the expense of his glucose and insulin. His insulin went up six-fold. Nothing else changed. That’s an example of this deeper phenotyping, how you can get so much more information, and it may seem kind of overwhelming to go to this extent, but there’s a lot of doctors who offer this type of care. I also want to emphasize that you can get back to the basics, because it’s not so much that you’ve got this really complex mapping of what’s going on with your entire body. Often, the solutions end up being the same.

Dr. Casey Means: Such a great overview of what a functional medicine or precision medicine approach is, which is really, in my opinion, and I know in yours too, the way that all medicine should be practiced. It’s looking at the complete picture and how that picture feeds into the core of physiology that actually leads to these symptoms and diseases we label as separate things, but which you know are very connected.

I was laughing when you were talking about triggers in the ATMs, because you mentioned how pregnancy was when someone might have felt like something totally went off the rails. For me, it was the day I started surgical residency. That was my trigger.

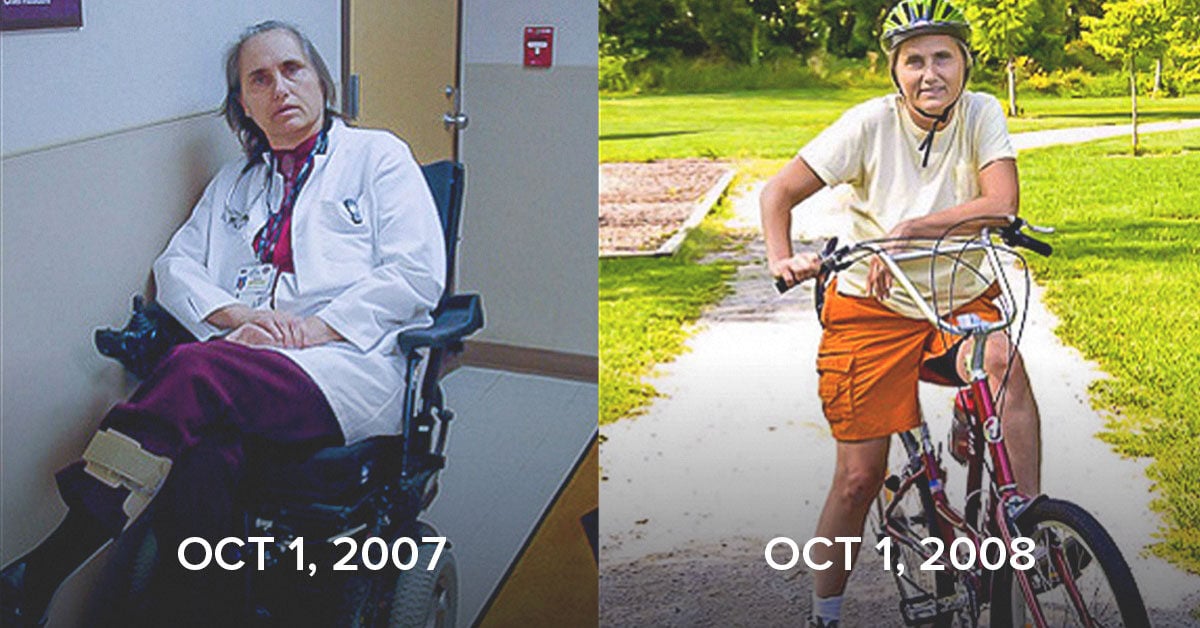

I went from being in absolute perfect health—thriving—to a shell of myself. It just felt like all my thoughts went from colored to black-and-white. I got acne. I got IBS. I got chronic neck pain. Fortunately, I listened to a lot of your books as I was walking to the hospital. I listened to Mark Hyman‘s books. I listened to Terry Wahls‘ books. I feel like it’s the most guardian angel thing that ever happened to me, that somehow I got exposed to functional medicine.

I’m in the hospital as a surgical resident, listening to all these books, and realized this trigger thing of, “Okay, the day I started, what happened?” Well, my sleep became erratic. My stress went through the roof. I started eating cafeteria food all the time. I basically stopped working out. I realized that, if I was going to fix my body, I had to dial these things back or change them. That’s exactly what ended up happening, and I completely restored my health.

The key thing that I thought about as you were talking is how the plan for each person might have different levers. They may have to lean into one more aggressively. For instance, in my life, things are much more under control, but sleep is still an issue for me, because I stay up really late. I work well late at night. For me, the food and exercise are dialed in, but sleep—I have got to lean into that lever.

When patients understand which levers they really need to pull, they can be empowered themselves to figure this stuff out, because it’s a lot. Doctors, especially right now, face huge challenges, in terms of time and volume, to get into all of this. But you as a patient can learn this, and you can advocate for these things, even if you don’t have access to a functional medicine doctor.

Building a Strong Foundation

Dr. Casey Means: While it can be very beneficial to be quite personalized on these things, there are a lot of basic things we can do to get us a lot of the way there. What are some of those things that everyone can focus on and implement to really help create foundational health in the body?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: The number one thing is to measure, because what you measure improves. You’ve got to know what your baseline is. If you’re going to assess where you are with your cardiometabolic health, you need to measure it. See where you start. That could be something as simple as an annual exam with a primary care doctor. Generally, you get a comprehensive metabolic panel, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1C—a three-month summary, more or less, of what’s happening with your glucose. It can give you an estimated average glucose, which I find very helpful.

You can look at some other markers of metabolic health, such as your waist circumference, or your waist-to-hip ratio. On the blood testing side, you can look at uric acid. I like uric acid a little bit lower in women than I do in men. I like it less than five in men. Many of the basic, inexpensive biomarkers can give you a lot of information. Checking your lipids can also be very helpful, but most conventional doctors are going to look at your LDL, HDL, triglycerides, and maybe your total cholesterol and just make a quick, yes-no decision about whether you need a statin. They’re not going to be talking to you about how to change the way you’re eating to affect that.

Number two, eat in a way that supports your metabolic health. The way you do that is to understand how food impacts your metabolism. The typical patient I take care of just assumes that things like eating an apple, having fruit on a daily basis, or eating sweet potatoes or other types of potatoes are really healthy. It’s often not until you get a continuous glucose monitor or a glucometer, and you check your glucose after eating, that you know there’s certain foods that really spike you. Dialing in your food is such an essential part.

Number three is really getting the exercise you need. In some ways, exercise is as close to a panacea as we have. When it comes to your metabolic health, you’ve just got to keep moving. One of the things that my patient who got started on a statin did during the pandemic was to start exercising three hours a day. He loves to close all three rings on his Apple Watch. He’s really focused on walking five miles a day. He spends a period of time in the gym he has at home. He has an elliptical; his wife likes Zumba. Figure out what you love to do.

I love heavy weights. I like to do heavy weights two-thirds of the time I spend on exercise, and about a third on cardio. I think that is associated with the best cardiometabolic health. But we all have to pick what we love the most.

Exercise is as close to a panacea as we have. When it comes to your metabolic health, you’ve just got to keep moving.

The fourth thing is related to the mind: mindset, purpose, meaning, love, connection, dealing with trauma so that your trauma isn’t dragging you around. Instead you want to behave and act from a place that’s very connected and loving. Those are some of the keys that are really important.

I was talking to a friend of mine recently. We did residency together. He and I calculated that between the two of us, we had about 2000 veggie burgers over the course of our residency. That is not a good thing to feed your cardiometabolic health. Veggie burgers sound so healthy, but it was fried in industrial seed oil. It was some kind of weird combination of something that looked like a vegetable, but it was made into a patty. It had a bun that had gluten and refined carbohydrates in it. Maybe that’s what led to my problem with blood sugar two years later, when I got pregnant. You’ve got me thinking about my triggers as well.

Dr. Casey Means: Those are such amazing foundational things everyone can lean into to help their cardiometabolic health. Working with patients, and with myself, I’ve learned that trauma doesn’t have to be something that’s a super overt, big “T” trauma, like a severe adverse child event. Everyone deals with trauma, and in a lot of ways, living is traumatic.

How do you think about trauma, and how do you talk to patients about trauma? How do you counsel them on how to start making headway on unpacking that?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: For almost all the patients I screen for trauma, their first response is, “Oh, I didn’t have a traumatic childhood.” They want to move on. They want to get to the recommendations and the supplements. I’ll say, “Well, hold on.”

I had a woman last week who was 50. She had started having some problems with her blood sugar. She had prediabetes, and was coming to see me to try to reverse this. I was asking her about adverse childhood experiences, and I had her fill out an ACE questionnaire. Her score, even though she said she didn’t have trauma, was about seven, which is very high.

She has an increased risk of autoimmune disease, stroke, and heart disease, all based just on her trauma. You put that together with a perimenopausal transition—decreased estrogen in her case—and I think that’s what led to this diagnosis of prediabetes. As we start to work together, generally, what I’m doing first is dealing with the biological issues. We do N-of-1 experiments. We got a continuous glucose monitor on her. We started doing some food experiments. I put her on a cardiometabolic food plan, and we noticed what happened to her glucose and to her glucose variability.

She noticed that her mean interstitial glucose and variability were starting to come down. It was about 25 when we first started working together—she was very spiky—and she had a mean glucose of about 110. I was trying to get her mean glucose to less than a hundred. Once we achieved that goal, I started to unwind what to do about trauma.

There are a lot of ways to go about dealing with trauma. It’s hard to give just a few bullet points, but understanding how trauma—small-T trauma or big-T trauma, as you described— gets biologically embedded is essential.

I think it’s one of our tasks as human beings to understand that there are some people who have trauma, and they develop psoriasis and irritable bowel syndrome. There are other people who have trauma who develop prediabetes. There are others who have trauma that leads to other issues related to that gene-environment interaction.

When dealing with trauma, the first thing is to understand what happened. We know that trauma is modulated by having someone you trust listen to you and hold you in your experience. If you didn’t have that as a kid, then we can do that now. Trauma-informed care is not quite the same as just going to a therapist and talking about it.

It has to be trauma-informed care because what works for trauma is a little bit different than what works for regular psychodynamic therapy. What I see with a lot of my patients is that regular therapists with less of an inclination toward trauma and how that shows up in the therapy relationship, often reinforce trauma. They don’t resolve it. Things like Internal Family Systems, Somatic Experiencing, the Hakomi Method—these are some specific forms of therapy that really help with resolving trauma and with helping people experience their full body, which is part of the aliveness we’ve been talking about, rather than cognitively disassociating.

Understanding how trauma—small-T trauma or big-T trauma—gets biologically embedded is essential.

Holotropic Breathwork is another interesting way of working with trauma, by creating an altered state with the breath and carbon dioxide. Then there’s the whole field of psychedelic medicine, which I know we’re not talking about today, but it’s a really interesting area that probably provides the strongest, most durable effect for addressing trauma. I’m not talking about taking MDMA and going to a rave. I’m talking about psychedelic-assisted treatment, where you’ve got someone who’s really skilled, who’s working with you to help you with resolving the trauma.

Dr. Casey Means: Examining some of these things can be beneficial for almost everyone, because so much of achieving the true foundational health we talk about has to do with behavior and choices. Much of our behavior and choices stem from our mindset and a sense of direction and purpose.

The Power of Kindness

Dr. Casey Means: We’ve had a lot of rough news about the increased risk for women with cardiometabolic disease, but is there any good news where women are doing okay compared to their male counterparts in regards to metabolic health?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: There is a ton of good news. Women tend to live longer. Women live until about age 80, men on average live until about age 73. We’ve got longer telomeres, which are those caps on the chromosomes that seem to be a measure of biological age, as opposed to chronological age. We’ve got this more adaptive immune system, and a greater dynamic range.

There’s something known as the jogging female heart. I love this concept, because if you just look at menstruation as an example, cardiac output can increase or decrease significantly during the menstrual cycle. Then, when you add on something like pregnancy, it can increase even more. We sometimes see increases of cardiac output that go from 20 to 50% in pregnancies. Women have this built-in dynamic range that is broader than that in men.

Women are also thought to be more social. In general, when you look at production of oxytocin, women fare better than men. In fact, Shelley Taylor at UCLA did this really interesting study around how women don’t do best with fight-flight-freeze, in terms of the stress response. They did better with a tend-and-befriend approach. That’s the way that women respond best to stressful conditions. It makes sense, because if you can imagine us on the Savannah, and our male partners are off on the hunt and we’re left in the village or the cave with an infant in one hand and a toddler in the other, the protection of the people in our group is really what’s going to protect us from predators.

There’s this other, more modern idea, which is social genomics. We think of ourselves as these stable human beings, but our genetics and the way our genes talk to our body, our epigenetics, change all the time, especially in response to other people.

I learned about this from George Slavich, of UCLA. He’s famous in the field for his work on social genomics and safety cues. He talks about something in particular related to genetics and how genes are expressed, called the CTRA, which stands for conserved transcriptomic response to adversity. According to this theory, we’ve got this tendency in our genes, when we’re exposed to adversity, to increase inflammatory tone; we increase pro-inflammatory cytokines. It helps us fight an infection, like if we get a bite from a predator. But this can backfire, and if you’re exposed to adversity and distress, it can lead to other problems like depression or developing cardiometabolic disease.

How do we modulate it? That’s where what I’m going to call the Doctor Means Effect comes in. An interesting randomized trial was published in 2017. The researchers found that you could change the expression of your CTRA most effectively with acts of kindness for others. You, Dr. Means, are one of the kindest people I know, and I feel like you figured this out way before George Slavich started to publish data on CTRA.

One bit of good news is that, even if you’re someone with a lot of inflammation, or you’ve got cardiometabolic disease, you can start to change this. You can change the way you interact with the environment. One of the most effective ways is how you relate to other people, and by doing acts of kindness. It’s one of the most effective ways to change that transcription of this particular set of genes.

Dr. Casey Means: First of all, thank you. That is one of the nicest compliments I’ve ever received. That’s an incredible that by being kind and doing acts of kindness, you can literally change your gene expression and the way your genome is transcribed. That should be frontpage news.

Even if you’re someone with a lot of inflammation, or you’ve got cardiometabolic disease, you can change the way you interact with the environment. One of the most effective ways is how you relate to other people, and by doing acts of kindness. It’s one of the most effective ways to change that transcription of this particular set of genes.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: It should be frontpage news. In this randomized trial, they looked at a few other things. They looked at self-care and at saving the world. I’ve got a husband who really cares about climate change, for instance. But those are not as effective as kindness toward others. It’s the Casey Means effect.

Dr. Casey Means: I think it is very much also the Sara Gottfried Effect. I appreciate that so much, and I’m so grateful for you. Thank you for sharing that beautiful piece of data, because I think it is extra motivating. Going that little extra mile to hopefully make other people’s days brighter can actually impact your own health, by changing genetic pathways. That is absolutely mind-blowing. Thank you so much for sharing that.

Is there anything you want to make sure we touch on before we conclude?

Dr. Sara Gottfried: My parting words are about coming back to your food. Food is the most important lever when it comes to metabolic health. A lot of people get lost in the details, and if you’re feeling overwhelmed, check your cortisol, and go back to your food. Really focus on eating in a way that best fuels you.

Continuous glucose monitoring is one of the best ways to discern that, but it doesn’t have to be at the cost of a CGM. You could use a glucometer to really understand how you react to food. That’s the simplest message I have. It’s a core part of this process, and it’s a place to start—the most important place.

A lot of people think, “Oh, I figured out my food. I did that five years ago.” But your body is dynamic; that gene-environment interaction keeps changing. What was ideal for you five years ago might be different than what’s ideal for you today. It’s an ongoing query I invite all of us into.

Dr. Casey Means: We’re basically shapeshifters; we’re changing all the time. That gene-environment interaction is changing all the time and so are our needs. Even if we’re under more stress for a short period of time, that may require us to increase our input of certain micronutrients to help regenerate our stress hormones.

It’s amazing. And now, for the first time, we have at least a little bit of visibility into that dynamicism, just through continuous glucose monitors and some of the single-time-point measurements, and if we’re getting our blood drawn more frequently and more in-depth than our standard panels. As you said, even using our standard yearly blood work—our cholesterol panel, complete metabolic panel, et cetera—we can still learn a lot.

I have yet to find a person who actually has it exactly perfect. There’s always room to keep going down that tunnel. I would plug your book, because it is a great resource for helping people who think they’ve figured out their diet, but still aren’t getting the results they want, to learn more and continue that journey.

It really opened my eyes to new things as well. I am so grateful for you and your work, this amazing paper that you published, your books, your speaking. Thank you so much, Dr. Gottfried, for coming and chatting with me today.

Dr. Sara Gottfried: My pleasure. So good to be with you, Casey.