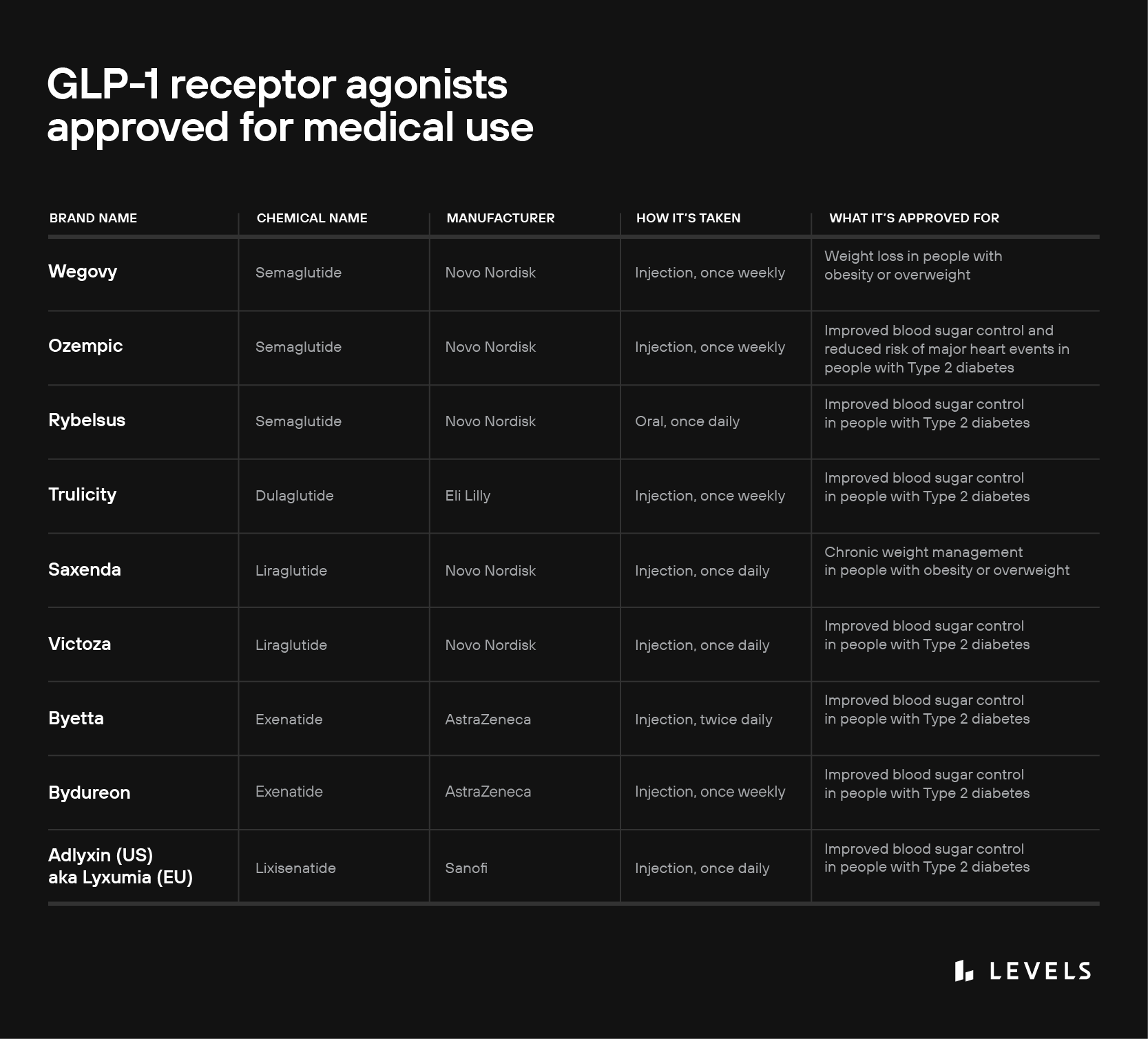

Sold under brand names like Ozempic, Saxenda, and Rybelsus, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists have been called “Hollywood’s new secret” and “TikTok’s favorite weight loss drug.” Pharma industry observers say this class of medication has officially reached “blockbuster“ status. But GLP-1 receptor agonists (sometimes written as GLP-1 RAs) are not a new miracle solution for shedding extra belly fat. They’ve been around for nearly 20 years and are intended only for the treatment of specific medical conditions.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are synthetic molecules that mimic the binding of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a hormone that helps our bodies regulate metabolism and appetite. Prescribed since 2005 for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes mellitus, the drugs more recently gained weight loss indications. In this piece, we’ll explore how GLP-1 receptor agonists work and their metabolic health benefits—as well as their side effects, safety profile, and other unknowns.

What is GLP-1?

GLP-1, a type of incretin, is a hormone that plays several essential roles in metabolism. First, it stimulates insulin production in your pancreas, a critical step that enables your body to utilize fuel sources (especially glucose) from the food you eat. GLP-1 also activates receptors in the brain and stomach, helping to regulate appetite and digestion.

When you begin eating a meal, your body releases GLP-1 within minutes. This primarily occurs in the intestines, though the pancreas and the brain also secrete the hormone. Levels peak 45-90 minutes later, then decline over several hours. During this window, GLP-1 helps your body use the sugar you’ve just consumed and limits potentially harmful glucose spikes.

The hormone delivers this benefit via several interlocking effects. First, as mentioned above, it triggers insulin secretion, which enables your tissues to absorb glucose from your bloodstream. Indeed, without GLP-1, your insulin response would be severely diminished. Second, GLP-1 suppresses your pancreatic secretion of glucagon—a hormone that helps drive up glucose levels when they’re too low, preventing hypoglycemia. (Insulin and glucagon are in a constant push and pull to keep your glucose levels stable.) And third, GLP-1 supports the health of insulin-secreting cells in the pancreas, called beta cells. By helping beta cells survive and thrive, GLP-1 contributes to an effective insulin response in the future.

In your stomach, GLP-1 slows down the muscular contractions that move food through your digestive tract. This decreases your gastric emptying rate, meaning that partially digested food remains in your stomach for longer. As a result, nutrients (including glucose) enter your bloodstream more slowly, reducing post-meal blood sugar spikes. The prolonged presence of food in your stomach also makes you feel full, thus lowering your appetite and helping regulate your total food intake.

Learn More:

Finally, GLP-1 acts directly on your nervous system. In the brain, neurons involved in appetite control have devoted GLP-1 receptors. Research shows that artificially activating these receptors inhibits food intake, even when the stomach is empty. This suggests that GLP-1 could suppress your appetite via direct, independent signaling in your brain—not just through your stomach. Lending support to this hypothesis, a recent imaging study demonstrated that GLP-1 reduces activity in parts of the brain involved in appetite and reward in people with Type 2 diabetes and obesity.

GLP-1 also stimulates nerve fibers in your gut, triggering gut-brain communication that helps to quell hunger. This type of signaling has been characterized as an “inter-organ neural circuit for appetite suppression.”

What are GLP-1 receptor agonists, and how do they work?

GLP-1 receptor agonists (also called GLP-1 analogs) are a class of synthetic chemicals that mimic the action of your natural GLP-1 hormones. These medications work by binding to and activating GLP-1 receptors throughout the body. But unlike natural GLP-1, which decays very rapidly (its half-life is just 2 minutes), synthetic GLP-1 receptor agonists are long-acting and remain active in your body for hours or days. That means your GLP-1 hormone pathways stay “on” for much longer than normal. This seems to lower blood sugar and improve insulin response in people with diabetes. It may also reduce body weight and strengthen cardiovascular health.

To maintain these benefits, however, you may need to continue taking GLP-1 receptor agonists indefinitely. Studies show that people who discontinue GLP-1 medications typically regain weight within several months. Researchers have also noted that 70% of diabetes patients discontinue GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment within two years, limiting the long-term efficacy of these drugs. This may be due to the drugs’ unpleasant side effects. We’ll continue exploring these concerns in the following sections.

GLP-1 agonists and diabetes

We’ve long understood that insulin helps to move glucose out of the blood and into cells, which use the sugar to generate energy. But in the 1960s, researchers discovered that other chemicals, secreted in the gut, are necessary for our bodies to quickly and efficiently produce insulin. One of these chemicals was eventually identified as GLP-1.

Several decades later, researchers noticed that the effects of GLP-1 are markedly reduced in people with Type 2 diabetes. Treating these people with a synthetic GLP-1 supplement, they reasoned, could help restore a healthy insulin response and bring down blood glucose levels. In 2005, the first GLP-1 receptor agonist (exenatide) was approved by the FDA for this purpose.

Today, several GLP-1 medications are indicated for improving blood sugar control in people with Type 2 diabetes (see table above). The drugs achieve these benefits by mimicking GLP-1’s effects:

- They stimulate insulin production by binding to beta-cells in the pancreas. This helps the body make use of glucose, preventing high blood sugar—one of the most damaging effects of diabetes. Importantly, this increase in insulin happens only when glucose levels rise (i.e., when the body needs insulin). As glucose levels fall and your insulin needs drop, GLP-1 agonists stop stimulating the production of the hormone.

- They slow digestion, reducing blood sugar spikes. Because food remains in your stomach for longer, nutrients (like glucose) pass more slowly into your bloodstream.

- They reduce food intake by binding to nerve cells in the brain and by slowing the emptying of the stomach (which creates a sensation of fullness). This overall reduction in calories can mean that you consume less overall carbohydrates (which become glucose), helping you maintain more stable blood sugar.

Today, we have strong evidence that GLP-1 medications are effective in treating Type 2 diabetes. A 2014 review of 15 scientific studies found that a combination of GLP-1 medication and insulin provided better glycemic control than other treatment regimens (including insulin alone). Specifically, the review found that compared to people on treatment plans without GLP-1, those taking the medications had 0.44% lower HbA1c (an important marker of blood sugar) and were almost twice as likely to hit the recommended HbA1c target.

A 2016 meta-analysis of 78 studies confirmed this result, finding that GLP-1 receptor agonists significantly lowered blood sugar levels compared to placebo. Similarly, a 2021 review of phase III clinical trials concluded that GLP-1 medications reduce A1c. The drugs have also been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease among people with diabetes. This evidence prompted medical societies (such as the American Diabetes Association) to include GLP-1 in their diabetes care recommendations.

GLP-1 agonists for weight loss

The use of GLP-1 medications to treat diabetes eventually revealed an additional metabolic benefit: weight loss. Obesity is the biggest risk factor for Type 2 diabetes, and substantial weight loss can help in reversal and remission of the disease, as well as reduced risk for conditions like high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, heart disease, and stroke. Medication that helps people lose weight may translate to significant improvements in metabolic health.

The GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide (brand name Saxenda) was approved for chronic weight management in 2014; and semaglutide (brand name Wegovy) followed in 2021. These medications seem to promote weight loss through two mechanisms that, again, mimic the action of endogenous GLP-1:

- They delay gastric emptying: The sensation of fullness caused by slower gastric emptying can prompt people to eat less, thus helping them lose weight over time.

- They increase satiety. By directly acting on appetite circuits in the brain, GLP-1 may cause people to experience less hunger. This could lead to lower food intake and weight loss. It could also cause people to choose lower-fat, less energy-dense foods.

While there is ongoing discussion about the balance and significance of the above mechanisms, it is clear that GLP-1 receptor agonists do reliably trigger weight loss, at least while people are taking the drug. Here is a small sampling of the research evidence:

- A 2012 meta-analysis examined 25 randomized controlled trials and found that GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment caused weight loss. People without diabetes lost an average of 7 pounds, while people with diabetes lost an average of 6.2 pounds over study periods ranging from 20 to 52 weeks.

- A 2021 review of 13 studies reached a similar conclusion, finding that GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment caused between 11.2 to 13.6 pounds of weight loss over periods ranging from 12 to 68 weeks.

- A 2016 meta-analysis examined 28 randomized controlled trials covering 29,018 people with overweight or obesity. The study concluded that the GLP-1 medication liraglutide was among the most effective pharmacological weight loss treatments.

Ready to learn more about your metabolic health?

Levels, the health tech company behind this blog, helps people improve their metabolic health by showing you how food and lifestyle impact your blood sugar, using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), along with an app that offers personalized guidance and helps you build healthy habits. Click here to learn more about Levels.

Are GLP agonists safe?

GLP-1 receptor agonists are not for everyone. Most people taking these medications experience gastrointestinal side effects, such as vomiting and nausea. One recent study found that these issues affected 90% of study participants in the first eight weeks of treatment. And though they typically last between several days and several weeks, they may persist for as long as you take the medication. For some, side effects are severe—especially at the doses needed to achieve their health goals. As mentioned above, 70% of diabetes patients discontinue GLP-1 treatment within two years; and feeling sick is the most common reason patients cited for stopping.

Bear in mind that these drugs are not a first-line defense against mild weight gain. They’re serious medications with strict usage requirements that are intended for chronic weight management.

Researchers have also raised concerns that GLP-1 receptor agonists could be linked to more serious illnesses. Among these is pancreatitis—a dangerous inflammation of the pancreas. Some argue that prolonged activation of pancreatic GLP-1 receptors could lead to an overgrowth of cells in the organ. A recent meta-analysis found no link between GLP-1 agonists and pancreatitis in people with Type 2 diabetes, but some case reports challenge this. This leaves investigators still unsure about the link, which is why GLP-1 medications currently carry warning labels around pancreatitis.

Similarly, some research suggests that there may be a link between GLP-1 agonists and thyroid cancer. The thyroid contains GLP-1 receptors, the long-term activation of which could plausibly be carcinogenic. Still, a 2022 meta-analysis exploring this link found no relationship between GLP-1 agonists and thyroid cancer or other thyroid illnesses. The authors cautioned, however, that the issue requires additional research, and that those with a family history of medullary thyroid cancer should avoid GLP-1 RAs. This echoes the findings of a 2013 review, which found “neither firm evidence in favor of this hypothesis nor evidence strong enough to rule out any such increased risk.”

Recent research also points to a link between the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide and worsening diabetic retinopathy (DR). DR is a serious complication of diabetes that can ultimately lead to blindness. While it may seem surprising that treating diabetes would worsen one of the disease’s complications, this seemingly paradoxical relationship is well-established: any treatment that abruptly lowers blood glucose can accelerate DR.

There are also concerns that semaglutide could cause a loss of muscle mass. A recent meta-analysis of 18 studies concluded that this effect is significant and warrants further investigation. For this reason, doctors may recommend pairing GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment with a high-protein diet and strength training to maintain muscle mass.

Bear in mind that these drugs are not a first-line defense against mild weight gain. They’re serious medications with strict usage requirements that are intended for chronic weight management. Doctors prescribe them to treat diabetes only when lifestyle interventions and other medications (like metformin) fail to control blood sugar. Healthcare providers may only recommend GLP-1 receptor agonists when BMI is over 30 (i.e., obesity), or if BMI is over 27 and the patient has an associated health condition, such as diabetes, kidney disease, or obstructive sleep apnea.

Finally, it’s important to note that GLP-1 medications are typically taken as an oral or subcutaneously injected medication (like dulaglutide, sold under the brand name Trulicity) in a single daily or weekly dose. This is very different from natural GLP-1 hormones, which rise and fall in complex patterns finely tuned to your food intake and other behaviors.

Levels’ Take:

Ultimately, GLP1 medications are not a sustainable solution to obesity or poor metabolic health for the vast majority of people. Only actual behavior and lifestyle changes—including eating a metabolically healthy diet and incorporating regular exercise—can produce lasting and effective health outcomes. Initial research is highly concerning that these medications have side effects that need further research before widespread adoption, significantly decrease muscle mass, and can cause significant weight gain after stopping. While reducing food intake, these drugs do not necessarily promote healthy, quality food intake, which is necessary for optimal metabolic health on the cellular level. Doctors and patients should be extremely cautious before prescribing or using these medications, and focus on safe, evidence-based dietary and lifestyle strategies for weight loss and metabolic health as first, second, and third-line treatment.