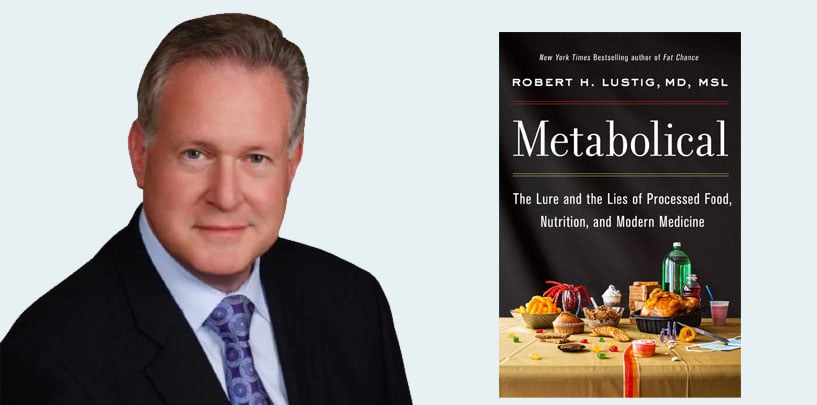

Casey Means: If you are a part of the Levels ecosystem, you know Dr. Rob Lustig, an incredible human being and the author of many books, including The Hacking of the American Mind, Metabolical, and Fat Chance. He’s written over 135 peer-reviewed papers. He’s a professor emeritus of pediatric neuroendocrinology at UCSF. He’s a Levels advisor. He contributes to many press articles and writes opinion pieces in major outlets. He is absolutely one of the most incredible and smartest humans I know—an inspiration for me and my journey through medicine.

What Are GLP-1 Receptor Agonists, and How Do They Work?

Dr. Rob Lustig: First of all, Casey, thank you for that very kind introduction. None of it’s true. It’s all a lie. I do have some opinions on GLP-1 agonists. Unfortunately, they are opinions rather than facts because this field is still in process. We don’t know most of what we think we know.

Casey Means: That in and of itself is interesting because many Americans are now taking these medications, and the fact that there isn’t really hard, clear science is very telling.

For people who are trying to understand the landscape—and you are an endocrinologist, so you can speak to this—what is GLP-1? What is a GLP-1 agonist medication, and how have they been used traditionally? How are they being used now?

Dr. Rob Lustig: What a complex question. All right, here we go. Endocrinologists have known about a hormone called glucagon for decades. Glucagon is the hormone we give to diabetics when their blood glucose goes too low. When they’re in hypoglycemia, we give them a glucagon shot to raise their blood glucose, because glucagon goes to the liver and gets the liver to release all the stored glucose in order to correct the hypoglycemia.

We learned back in the early 1980s that there’s this bigger protein called preproglucagon. The alpha cells of the pancreas that make it have a different way of chopping it up into different pieces for different purposes. People started looking at what these pieces were. They found pieces that seemed to cause the beta cell to release more insulin, not less. They called these pieces glucagon-like peptides because they look like glucagon, but they’re a little bit different. Those then got to the pharmaceutical industry, and people started making the first GLP-1 agonists.

The first successful GLP-1 agonist was actually obtained from Gila monster spit. It’s one of the reasons the Gila monster is poisonous. That peptide was called exenatide, also marketed under the trade name Bayada. We started using Bayada in pediatric and adult endocrinology for taking care of diabetes because it seemed to kick the beta cell to release more insulin. That was a good thing for a while. Bayada had reasonable success as an adjunct to diabetes therapy for several years. Over time, as you’d expect, the pharmaceutical industry started making better, longer-lasting, more potent agonists that would do the same thing in terms of being able to treat diabetes.

They came up with a drug called Semaglutide, or Ozempic. Back in about 2017, 2018, the data started rolling in that Ozempic was a better adjunct for diabetes therapy than Bayada. They saw that there was a modicum of weight loss as well. Some brilliant guy at Novo Nordisk said, “Well, if this is causing weight loss, maybe we can give a bigger dose and it will cause more weight loss.” That resulted in this branded version called Wegovy. Both Ozempic and Wegovy are the same medicine. They’re both semaglutides. They’re both GLP-1 agonists. They look like glucagon, but they’re not. And they bind to a specific receptor. That receptor exists in several places in the body. One is in the pancreas, to increase the amount of insulin, which then better controls blood glucose. That’s why it’s used for diabetes.

The fun part, if you will, of this molecule is that there are receptors for GLP-1 in the brain stem—not the hypothalamus, but lower in the brain stem, mostly in the nucleus tractus solitarius. The GLP-1 analog binds to those receptors and basically tells your brain you’ve eaten. This is part of the satiety signal, and we’re basically hijacking it. And because we have these longer-acting medicines than what our own GLP-1 can do, it can last longer. It basically reduces total food intake, and this ultimately results in weight loss.

Novo Nordisk got approval for both Ozempic and for Wegovy. Eli Lilly has worked their own medicine, which is a GLP-1 analog, but also has secondary effects on a second receptor involved in satiety called GIP, which is gastric inhibitory peptide. It has double duty, and that drug is called Tirzepatide, also known as Mounjaro. It has been approved by the FDA for weight loss as well.

These are now available, and they work. There are good data that show you can lose a significant amount of body weight with these medicines. Obviously everybody and his brother wants it. Unfortunately, it’s $1,300 a month. Only the people in Hollywood are getting it. In fact, there’s a shortage because everyone in Hollywood’s on it. Maybe that’s why you moved to LA, Casey—only kidding.

Casey Means: I’ve lived in LA for two months, and it is the ultimate conversation starter in LA. People ask, “Oh, are you on Ozempic? Are you trying xyz?” It is wild. In Bend, Oregon, where I moved from, no one was talking about Ozempic. But in LA, it’s literally everywhere. Doctors are talking about it. It is a tidal wave, which is one of the reasons I wanted to talk to you about it. I want to make sure I understand the science, because medical school was a long time ago.

Glucagon in the body naturally raises blood sugar, but it also stimulates the beta cells to secrete insulin. I’m confused about how those two things happen together. If it’s stimulating insulin secretion, why wouldn’t that lower blood sugar?

Dr. Rob Lustig: Well, it does lower blood sugar.

Casey Means: But what is the glucose-raising effect you were mentioning?

Dr. Rob Lustig: The glucagon was raising it, but the GLP-1 is not, because it’s actually stimulating insulin to keep the glucose low, which is why it works in diabetes.

Casey Means: But it’s acting as an agonist.

Dr. Rob Lustig: That’s right. It’s acting at the GLP-1 receptor, not at the glucagon receptor. Those are two different receptors.

Casey Means: Got it. Its main point is to stimulate insulin secretion. How is that conducive physiologically to weight loss? We know from your work and the work of others that excess insulin—hyperinsulinemia—is going to potentially contribute to insulin resistance and storage of fat. How’s that working?

Dr. Rob Lustig: This is the dichotomy, and one of the reasons we don’t understand this very well. When you ask the question, Why does this work?, the answer is we don’t really know. If you are actually increasing insulin release, which these medicines do, then you should be forcing more energy into fat, but yet people are losing weight. How do you rationalize that? We don’t really know. But people who take these medicines eat much less. They are losing weight because they are eating less, irrespective of the fact that their increased insulin secretion should be driving more fat gain.

Are these people losing weight because they’re losing fat? Or are these people losing weight because they’re losing muscle, or something else entirely? The data on this is very clear. You put these people in DEXA scanners, so you can look at body composition changes. People taking Ozempic and Wegovy and Mounjaro are losing equal amounts of muscle and fat. Is that a good thing? Absolutely not. That is by far and away not a good thing.

When you lose both muscle and fat, your body composition is changing in a way that is consistent and indicative of starvation. If you’re 65 or older and you lose muscle, you’re going to die. Sarcopenia, which is loss of muscle mass, is one of the hallmarks of aging, and one of the hallmarks of early death. Just read Peter Attia’s book, Outlive, about how important it is to maintain muscle mass.

This drug is not maintaining muscle mass. You are losing equal amounts of muscle and fat. Now, does that improve how you look in a bathing suit? Sure. But does that improve how long you’re going to live? Not a bit. This is a major issue. When you look at people who’ve taken Ozempic, you can actually see it because their muscle just sort of dissolves from their face. They look like they had lipodystrophy, like the people who were on protease inhibitors for HIV. It’s called Ozempic face for that reason, because they’re losing muscle from places that they shouldn’t be. This is a big issue.

Yes, Ozempic and Wegovy basically tell your brain you’ve eaten, and that’s good. But they tell your brain you’ve eaten and make your GI tract think you’ve basically stuffed yourself. You have lots of side effects related to nausea, vomiting, and, in rare cases, pancreatitis. There’s a concern about thyroid cancer. There’s a concern about pancreatic cancer. At least with the old versions of GLP-1 analogs like Bayada, there was a definite relationship to pancreatic cancer. That has not yet shown up with Ozempic and Wegovy, but they haven’t been out on the market long enough for us to be able to see that in post-marketing studies. That’s a continued concern.

Here, we’re bypassing the problem. We’re basically telling your brain, “Yeah, you’re fat. So starve.” And an emaciated fat person is not a thin person.

I just read about a set of cases of patients who now have gastroparesis. They have paralyzed intestinal tracts, paralyzed stomachs, that can’t move food through the intestine at all, even though they’ve been off the medicine for six months to a year. These are things that happen in post-marketing once it’s available to the entire country, or even the entire world, that weren’t necessarily obvious in the original studies to get it approved because it was tested in a much smaller population. The final story on Ozempic and Wegovy has not been written.

There are people who are absolutely excited about it because it’s the first time a drug has actually worked for weight loss. Every other drug for weight loss has been pulled off the market for side effects. Well, guess what? This one has side effects, too—different kinds of side effects than before, but side effects nonetheless. This is not something for the squeamish and it is not something to take just to fit in a bathing suit.

Does it make a difference for people who are morbidly obese? Can it improve their lives? Yeah, sure. But you’re bypassing the problem. You’re not fixing the problem. The problem is not that you have GLP-1 deficiency. No one has GLP-1 deficiency. That’s been looked for. There is not one case of GLP-1 deficiency. You are not treating a hormone deficiency with a hormone. If you have diabetes, you’re treating it with insulin. That makes sense because you’re actually fixing the problem. Here, we’re bypassing the problem. We’re basically telling your brain, “Yeah, you’re fat. So starve.” And an emaciated fat person is not a thin person.

The Potential Long-Term Effects of Widespread Use of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Medications for Weight Loss

Casey Means: Do GLP-1 agonists actually improve metabolic health in any way? Do they improve our mitochondrial function, improve our oxidative stress, improve the things in our cells that are actually going to make us fundamentally, metabolically healthier? Is there a clear understanding of this?

Dr. Rob Lustig: This drug’s job is not to improve metabolic health. Yes, if you lose weight, you are losing fat, and you’re losing fat from places that are metabolically relevant, like your visceral adipose tissue, your liver. There are studies that show reductions in visceral adipose tissue and reductions in liver fat with Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro, and that’s good, but it’s because of starvation.

The loss of liver fat, the loss of visceral fat—the things that improve metabolic health—are also coming with a loss in muscle mass, which of course is where most of your mitochondria are burning up your energy anyway, and you are losing muscle in a way that is potentially unhealthy and even downright dangerous long-term.

Now, does it improve mitochondrial function? If it reduces the sugar content of your diet because you are eating less, then that would be a good thing, and that would improve mitochondrial function. But what if you were taking Ozempic and Wegovy to lose weight, but you decided to go on a dessert diet and were supplying yourself with extra sugar. That sugar is still the same mitochondrial toxin whether you’re on Ozempic or Wegovy or not, because it still has to get metabolized and it’s still going to interfere with AMP kinase and ACADL and CPT-1 in your mitochondria. You are still going to have mitochondrial dysfunction. These drugs do not fix that. What they fix is your overeating. Can you stop your overeating and still be metabolically unhealthy? Absolutely. It’s not going to fix that. But if you eat less, that’s at least less burden on your liver and on your pancreas. Yes, there are improvements in metabolic parameters related to weight loss, but not related to dietary improvement. That’s what it comes down to.

These medicines are unbelievably expensive. They’re $1,300 a month at the moment. If everyone in America who qualified for Ozempic or Wegovy or Mounjaro got it, that would be a total of $2.1 trillion a year to the healthcare system. The current healthcare system currently expends $4.1 trillion a year. This would be a greater-than-50% increase. In order to get some weight loss and a mild improvement in metabolic dysfunction, you can get the same amount of weight loss with a 70% improvement in metabolic dysfunction. If we just got sugar consumption in this country down to USDA guidelines, instead of spending $2.1 trillion, we would save $1.9 trillion. To me, this is a Band-Aid. It’s not solving the problem.

It’s not fixing the metabolic dysfunction because it’s not targeted to do so. It’s acting in a different place and it’s basically creating a different problem than the one you had. You had obesity, now you’ve got starvation. How good for you is starvation? Not so good, with a whole lot of side effects to go with it. There’s nausea and vomiting. There are a lot of people who go on one of these drugs and are on it for a weekend. They come right off it. Two thirds of the patients who go on these medicines come off them within a year because of the side effects—not because of the cost, but because of the side effects.

The loss of liver fat, the loss of visceral fat—the things that improve metabolic health—are also coming with a loss in muscle mass, which of course is where most of your mitochondria are burning up your energy anyway, and you are losing muscle in a way that is potentially unhealthy and even downright dangerous long-term.

The cost doesn’t help. I don’t see this as being the answer to our metabolic health crisis, both from a physiologic level, from a side-effects level, and also from an economic level. It’s a Band-Aid, albeit a better Band-Aid than we had before. But no, this is not going to be the answer. We’re not there.

Casey Means: What I’m hearing you say is that there’s essentially a $4 trillion delta between tripling down on this, potentially spending $2.1 trillion on giving this to everyone who qualifies for it. And that may not really reduce any healthcare costs. We’re basically adding $2.1 trillion to the system, versus if we focused on getting sugar out of food and getting people access to the real, whole, unprocessed food that feeds the gut and supports the liver, we could actually cut $1.9 trillion from our $4.1 trillion healthcare costs.

We’re really looking at a monumental kind of mis-investment in resources that could go toward something else, but of course feeds the pharmaceutical industry’s bottom line. It’s been interesting to see the incredible amount of payments Novo Nordisk has made—consulting fees and payments to doctors—over the past few years, really trying to, I think, influence the primary care, obesity medicine, and endocrinology landscape.

You can’t help but wonder what’s happening there. The push toward classifying obesity as a chronic disease and toward securing federal funding and insurance coverage for these medications feels like a big force essentially using taxpayer money to go toward a pharmaceutical intervention, rather than a food intervention.

A lot of people say, “Well, the food is too hard.” But I step back and think, If we’re talking about trillions of dollars here, is it really that hard? Could we not figure this out with trillions of dollars, how to give people whole food and get rid of the sugar? It just feels like an interesting interplay of advanced science and technology—and I’m all for innovation—but also a distraction from the core issues we’re facing.

Dr. Rob Lustig: That’s how I view this. I view this as a distraction, unfortunately. I wish it were not. I wish there were a better answer. What I see is that there are people who are extremist because of their obesity and they need help. I’m a scientist, but I’m also a doctor, and I also have compassion. I recognize there are people who actually need help, and this should be available for them. I am not against these medicines. Hell, I used Bayada. I’m retired now, so I haven’t used these newest GLP-1 analogs, but I used to use the other one for the right patient.

I’m not against this for the right patient, but to throw this out willy-nilly is missing the point. This is exactly what we did with bariatric surgery. We found that when we did bariatric surgery on a host of people—and not in a clinical research setting, but rather out in the community—one third of patients gained the weight back. The reason was their problem was not one bariatric surgery could fix. They had food addiction or struggled with stress eating. The bariatric surgery didn’t fix those things. Bariatric surgery will fix hunger. It won’t fix reward pathways or stress.

You have to screen for who’s the best patient to use it in. We’re not doing that. We’re basically treating them all like they’re all the same—basically that they all have a moral failing, and that’s the whole story. That’s complete utter garbage. I’ve spent my entire career debunking that notion. Unfortunately, there are still doctors out there who think that obesity is a moral failing, and so they’re going to say, “Well, you haven’t responded to anything else.” That’s because you haven’t actually dealt with the problem.

Look, the medicine does work, and as soon as you stop it, all the weight comes right back. How good is that? Is that going to solve any problem? All you’re going to do is waste this $2.1 trillion a year, and it only works as long as you’re on it. As soon as you’re off it, all the weight comes roaring back, just like if you did a starvation diet and then stopped. This is something you have to be very circumspect about. You have to know your patient. You have to evaluate your patient for whether or not this is the right thing to do, whether there’s any other way to deal with this.

Until we fix the food, we’re not going to fix this problem. We have to fix the food to fix this problem. By the way, when we do fix the food, we’ll also fix climate change. You get two for one. Fixing the food is where I’ve spent my entire retirement. Trying Ozempic and Wegovy is not fixing the food. Yes, it will help some people, but it may actually make more people worse for the reasons I’ve mentioned.

Casey Means: Does this improve metabolic parameters over the long term for people with Type 2 diabetes, as well as improve survival and reduction of other comorbid diseases that may cause premature mortality? Does it seem to prevent some of those outcomes and extend life, or is it mostly improving the parameters like glucose levels? More broadly, does it improve insulin sensitivity in a patient with Type 2 diabetes or does it just reduce blood sugar levels?

Dr. Rob Lustig: These are really, really good questions, and we don’t have the answer to those. What you’ve got here is a give-and-take. You’ve got to trade. Yes, you’re losing fat, but you’re also losing muscle, and probably micronutrients you need because you’re eating less. There are going to be some good things that come from reducing your weight and there are going to be some bad things from reducing your weight.

Ultimately, we don’t have the answers to how these drugs impact cardiovascular events and mortality. These drugs haven’t been around long enough to be able to look at that. This is very similar to the question we had with bariatric surgery: Does bariatric surgery improve lifespan? In some patients, yes, but not in everybody. In fact, bariatric surgery increases the risk of alcoholism by a lot. Those people were sugar addicts before, and now you’ve made it so that they can’t get their fix because you’ve put something in there to keep them from being able to consume it. Instead of eating their fix, they’re going to drink it.

Until we fix the food, we’re not going to fix this problem. We have to fix the food to fix this problem.

I’ve seen at least anecdotal reports that Ozempic and Wegovy are increasing the risk of depression and suicidal ideation because they’re interfering with your ability to generate reward. If you’re a sugar addict, the only thing keeping you from the abyss is your next dose, and you now are not consuming it. Maybe that’s going to be a problem in terms of reward.

Think about Rimonabant, a medication put up for approval at the FDA in 2006. Rimonabant, also known as Acomplia, was marketed by Sanofi in Europe and was approved by the European Drug Commission. It was an endocannabinoid antagonist, so it bound to the same receptors that marijuana binds to. We have endocannabinoids in our brain. People who went on Rimonabant lost a lot of weight because you suppressed reward by using these medicines. Well, when you suppressed rewards, you suppressed food intake, and you also increased the number of people who jumped off bridges. A significant number of patients who took Rimonabant ended up with major depressive disorder, and a lot of them committed suicide. The US never approved the drug.

Casey Means: I had been under the impression that some of the rumblings about this impacting mental health in a negative way were potentially due to gut and microbiome issues. And who knows? I hadn’t made the link between the reward circuitry.

You can’t mess with the gut and not expect something to happen. The gut is everything. And I’m preaching to the choir, but that to me feels like a Pandora’s box we’d want to understand before mass-prescribing these drugs to kids as young as 12, which it’s now approved for.

The Challenge of Getting Off These Medications

Casey Means: What do the data say about weight regain after stopping this? How many people are gaining it back?

Dr. Rob Lustig: If you stop it, the weight comes back. It’s that simple. This means you’re staying on it forever. The reason is because you’re not solving the problem. You are bypassing the problem. The problem is still there.

Casey Means: Do patients who go off it become insatiably hungry? What is that experience like?

Dr. Rob Lustig: That is what I hear. You basically put the weight back on within a month or two. This is sort of a stopgap measure, and as soon as you stop it, it will roar back. It’s not solving the problem, it’s Band-Aiding the problem. In some cases, do you need a Band-Aid? Sure. But you have to be very circumspect about whom you’re going to use this in. Right now, we’re not doing that because it’s new.

Everyone uses it. We have all these early adopters. And then we find out that maybe this isn’t such a good idea. Then the pendulum swings back the other direction: nobody should be on it. Ultimately it will find some place in the middle where it will settle, because that’s the nature of how all new therapies get rolled out. It gets used, then it gets overused, then it gets underused, and it comes back to the center. Right now we’re in the overused state.

Casey Means: There are going to be millions of Americans on this medication, and there are going to be a lot of people who have an awakening about the fact that this is not a panacea, it’s not a silver bullet. They might have horrible side effects, they want to get off it. There’s probably going to be a huge opportunity for people, while they’re on the medication, to also start plans to set themselves up for success for getting off it, and maybe use the medication as a jumpstart to get the motivation and energy to then do the things that actually get at the root cause.

Let’s say someone’s on Ozempic, and this information is kind of freaking them out, and they’re thinking they might want to eventually get off it. What are some of the steps someone could take to really set themselves up for success when weaning?

Dr. Rob Lustig: I couldn’t agree more. Ultimately these medications will be good jumpstarts. In other words, that means they will be adjuncts to other therapies, ways of getting people to have early success so that they can feel some self-efficacy—some agency—and that they can do something to help themselves and ultimately carry that forward. I’m totally for that. If that is ultimately how Ozempic and Wegovy are used, I will likely be a proponent for them. That’s not how they’re being used now.

If you can see that changing your diet will be something you can actually follow through on and Ozempic and Wegovy help get you there—to that point where you change what’s in your pantry and subdue the cravings—that would be a fine way to do it. It could be a short-term jumpstart, and then you come off it.

But that means that you need a nutritionist involved. That means that you’re going to need your primary care physician to really take command and help you navigate how to do this and help you navigate the grocery store going forward. I could see these drugs being an adjunct to a more codified lifestyle program, and then maybe there’ll be a good value to them.

Casey Means: Let’s say someone is morbidly obese and they just don’t have the energy or motivation to get started. They get some early success with a medication like this—they get more energy, they’re able to move more. I can imagine a situation in which, if they’re able to get a support team around them—learn how to cook, shop at the grocery store, prepare whole foods, start a resistance training program so they lose as little of the lean muscle mass as possible, maybe even build some, dial in on protein and amino acids and prevent the sarcopenic effect, work on the mental health piece—then maybe it helps them eventually move from one state to a much better future, and eventually get off the medication. But if none of that happens, the body getting less of something crappy is not the equivalent of health.

Dr. Rob Lustig: If something is toxic, then less of something is less toxic, but that doesn’t make it healthy.

Using GLP 1-Receptor Agonists in Kids Is Not the Answer

Casey Means: You are very familiar with evidence-based ways for sustained weight loss, especially in children. You’ve done some research in your work on this. The American Academy of Pediatrics, in their obesity guidelines, indicated that these medications and other pharmacologic agents for obesity could be used in children as young as 12.

What are the factors that actually allow children to lose weight in a sustainable way? What do you think about the AAP guidelines?

Dr. Rob Lustig: The AAP guidelines that came out earlier this year said two things. One I agree with and the other I disagree with. It said that obesity is a problem. I agree. Obesity is a problem. They said that pediatricians have ignored obesity in the children they see for far too long, and that by saying to parents, “Oh, it’s just baby fat, it’ll go away,” they’re actually perpetuating the problem. They called the pediatricians on the carpet for basically ignoring the problem as the problem festered under their feet. That part of the AAP guidelines I agreed with.

Then there’s the second part, which I disagree with. It said that because obesity is such a problem and because it is a disease and because kids aren’t getting better, you are entitled and rightfully, appropriately commissioned to use medication as young as 12 years old.

Now look, I used medication when I was head of the OBC program at UCSF. One quarter of the patients I took care of were on Metformin. The reason they were on Metformin was because Metformin was targeted at the problem. These kids had insulin resistance. They needed their insulin to go down. I knew that as long as their insulin stayed up, they were going to continue to gain weight because insulin is the energy-storage hormone. Get the insulin It worked at where the insulin problem was: the liver. It was targeted to improve insulin sensitivity at the level of the liver by increasing the enzyme AMP kinase.

AMP kinase is the fuel gauge on the liver cell. It tells your liver to make more mitochondria. If you increase AMP kinase activity, you’re going to make more mitochondria, which means you’re going to burn energy better and faster, and you’re going to improve insulin sensitivity. You then have a chance to get your insulin down and have weight loss. That’s why we used it, because it was directed at the correct problem.

I also knew from my own studies from back in the nineties, when Metformin first came out, that if the kids consume soft drinks, Metformin was useless—it did not work. They were poisoning that AMP kinase. You can’t raise your AMP kinase when it’s being poisoned. It doesn’t work. Soft drinks were the antithesis of Metformin activity, and I had to get people off the soft drinks before the Metformin would work. I had to do both: stop the soft drinks and do the Metformin. But when I did that, it would work.

We have to fix the food environment in the schools. We have to fix the food environment in the grocery store so that the food environment at home can ultimately be fixed.

I had plenty of good data to show that, and I published this. This was out in the world. How many pediatricians adopted that? Only the ones who listened to me, which is not enough. Can we ultimately get kids to change their diet so they don’t need medicine? No, because the food environment they find themselves in is unbelievably toxic. We have to fix the food environment in the schools. We have to fix the food environment in the grocery store so that the food environment at home can ultimately be fixed. And we expect parents to somehow be the gatekeepers. The problem is they can’t be. It’s too difficult. We’ve made it too difficult.

And of course, the food industry’s goal is to make it too difficult. In addition, most of those parents are sugar addicts themselves. How are we going to fix the food for the kids if we haven’t fixed the food for the parents? How do you expect the kids to get better when the parent is the sugar addict and is still bringing Oreos into the house? That doesn’t work. It requires a much bigger effort, and not expecting that the parent alone is going to be able to solve this problem.

Giving drugs to kids is not the right answer, even though I did it, but I did it for the right patient for the right reason at the right organ. But just throwing Ozempic and Wegovy at kids is not the answer to this problem.

Casey Means: Eat Real is an amazing organization that’s trying to change food in schools.

Dr. Rob Lustig: We’re fixing K-to-12 food in schools because it’s actually cheaper to make real food than it is to make processed food, if you know how. That’s what Eat Real does. Everybody out there, go to eatreal.org, look it up, support it, get your school cafeteria food services director to call us.

Casey Means: Absolutely. Nora LaTorre, the founder, is a powerhouse. That organization is at the nexus of children’s health, family health, school, food, and the environment because of the way we’re growing food, and it’s so powerful.

Dr. Rob Lustig: I’ve got two female forces in nature. I’ve got you, and I’ve got Nora.

Casey Means: Rob, thank you so much. This has been such an interesting conversation. I’m pretty upset about the AAP’s guidelines. It’s like we’re saying bariatric surgery and drugs are the answer, instead of fixing food, even though it would be cheaper in the long run to fix food.

In the guidelines—and I read the entire thing—they’re saying it’s a social justice issue, which is true. That’s why we have to lean on medications and surgery because it’s almost easier. I wish the AAP got on a grandstand and said, “You’ve got to fix the food.” Why isn’t every doctor on that panel, on every platform possible screaming for better food? We all have voices. Why is that not happening?

On that note, Rob, it has been such a pleasure. I learned so much. I’m so grateful for you and every single thing you’re doing in the world. You are changing the world with every word you say and everything you do.