Levels employees are not, for the most part, soda drinkers. That was the first thing we learned when we started logging the results of our Coke Experiment. Our Slack was full of unenthused reactions to downing what was, for many, their first Coke in years: “chest burning!,” “so many burps,” “Coke tastes pretty good … my stomach hurts now.”Our aim, however, was serious: We wanted to back up with controlled data something we saw anecdotally from our members all the time: Going for a short walk after a meal can help blunt the rise in blood sugar caused by the carbs you just ingested.

There’s a good physiological reason for this effect: muscle contraction (as happens when you’re moving) can spur glucose uptake [see Science below for more on this]. But we were curious if we’d see the real-world impact in our Levels dashboards across most employees with a controlled glucose load: a standard American can of Coke.

“To improve metabolic fitness, time bouts of even moderate exercise strategically throughout the day to blunt post-meal blood-sugar surges.”

We first tried this experiment using the 75g-glucose drinks used by doctors administering an oral glucose tolerance test (common for pregnant women to test for gestational diabetes). But in addition to universal disgust at the overly sweet orange drink taste, the intense glucose spike and crash left more than one employee feeling bad for hours afterward (said one, “I got super shaky, sweaty hands, blurred vision, had to lay down in bed immediately”). We also felt Coke was more relatable. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), between 2011 and 2014, nearly half of adults (and 63% of people 19 and under) in the United States consumed a sugar-sweetened beverage on a given day. Although consumption is declining in some groups, it’s still far too high.

Here’s what we found out.

Note: This was an informal experiment, not a clinical trial. It is limited by the small sample size. The subject warrants further study under controlled clinical conditions.

The Experiment

The Experiment

We hypothesized that people who were active after consuming a glucose load would see a reduced blood glucose rise and peak.

Methodology

We recruited subjects from among Levels employees worldwide (we are a fully remote company). Ages ranged from early 20s to mid-40s. Eleven people (3 female, 8 male) completed both the active and stationary portions of the experiment, and another 4 (all males) completed at least one of the portions.

We sent each participant two cans of Coke, all from the same source, to ensure uniform sweetener type (high fructose corn syrup) and amount (39g carbohydrates). (Note that HFCS contains both fructose and glucose, and the ratio varies. This 2014 study found that Coke was 60% fructose and had roughly 21g of glucose.)

Why fructose is bad for metabolic health

Is fructose bad for you? Fructose is a natural sugar, but as an added sweetener, its metabolic impact can be severe.

Read the ArticleWe asked each participant to consume the full can in a fasted state, at least one hour after waking up, and to consume no other food during the trial period. We also asked them to consume no alcohol the night before (alcohol can actually lower glucose production).

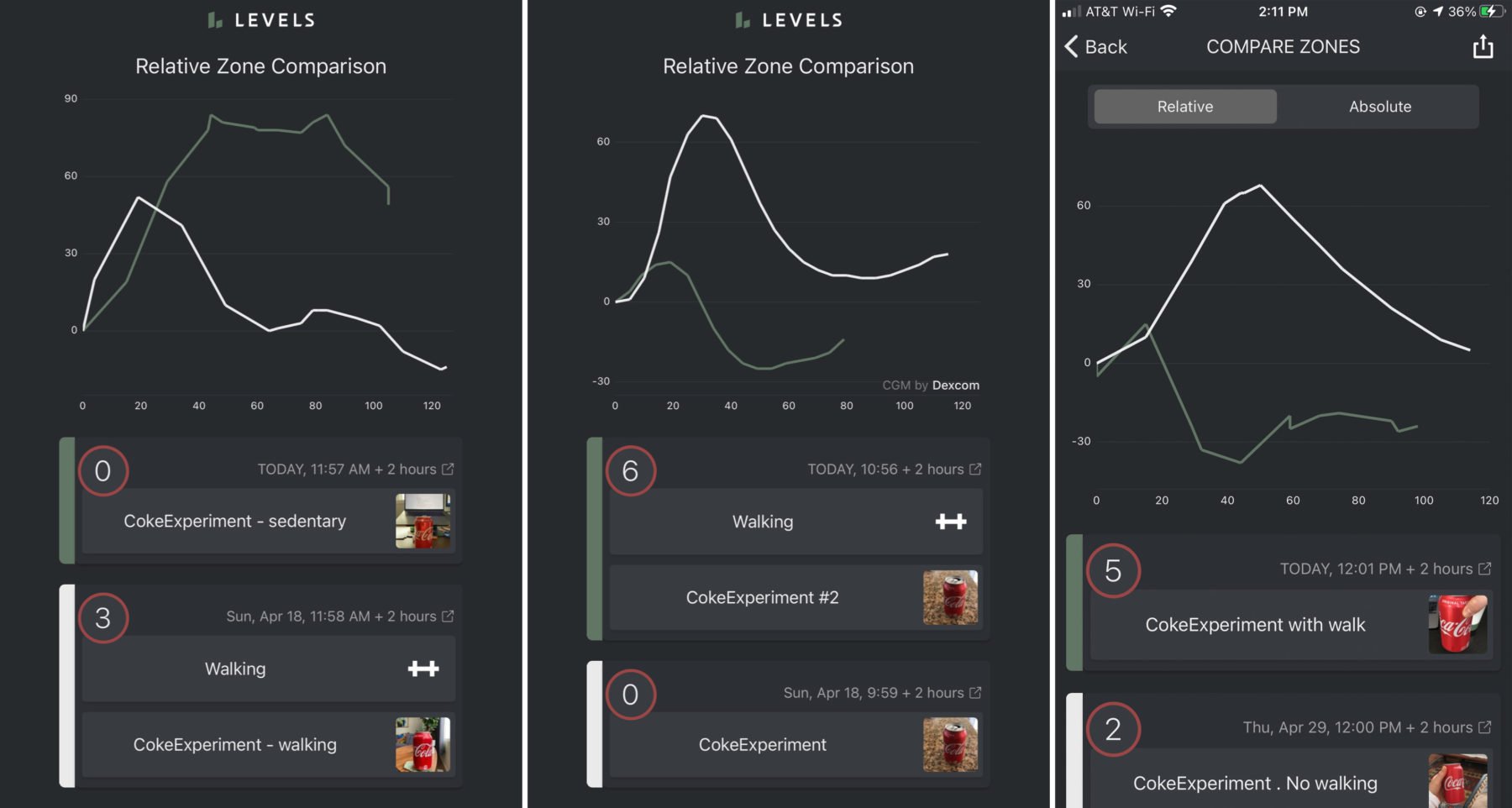

For the stationary (control) portion, we asked people to avoid moving as much as possible for two hours after drinking the Coke. For the activity portion, participants went for a walk immediately after finishing the Coke and continued walking for at least 30 minutes, up to 2 hours.

“Our skeletal muscle tissue is a huge glucose sink. When we are moving, muscle contraction can enable our muscles to take up glucose from the bloodstream without a corresponding rise in insulin.”

All participants used Levels to record their glucose response and activity, using either an Abbott Freestyle Libre or Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitor. None of the participants has a diagnosed metabolic condition.

By having participants complete both the active and stationary trials, participants served as their own controls. This allowed us to reduce the effects of individual glucose response differences, which can result from several factors, including their unique microbiome, micronutrient status, sleep, and genetics.

The Results

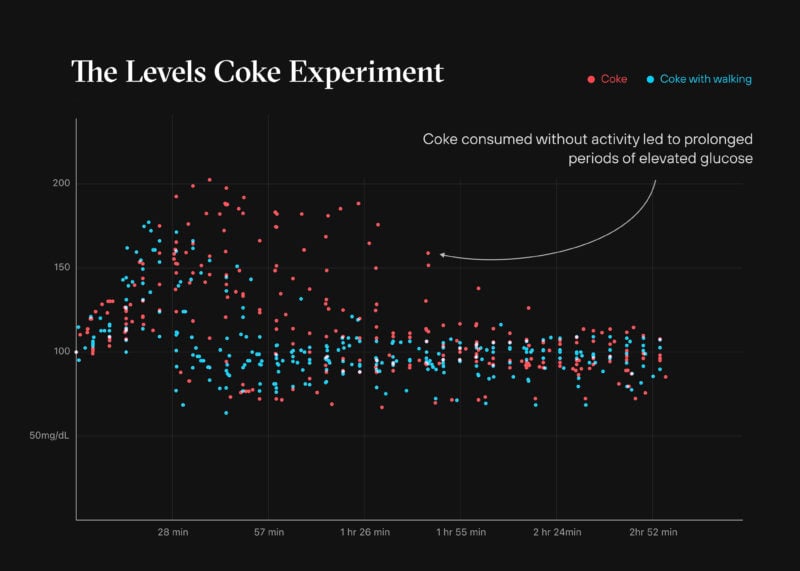

For the 11 participants who completed both portions of the experiment, we found the median delta of glucose rise between a walk and no walk to be 32.8%. The median glucose peak for activity versus no activity decreased by 18.5% (162 mg/dL to 132 mg/dL). In other words, for most people, taking a walk after a Coke significantly decreased their blood sugar response.

The individual responses varied considerably. One participant saw a nearly 100 mg/dL difference between the two portions of the experiment, while another actually had an inverse response: a higher peak with the walk than without. This underscores the individuality of glucose response and the number of potential confounding factors, including sleep and stress.

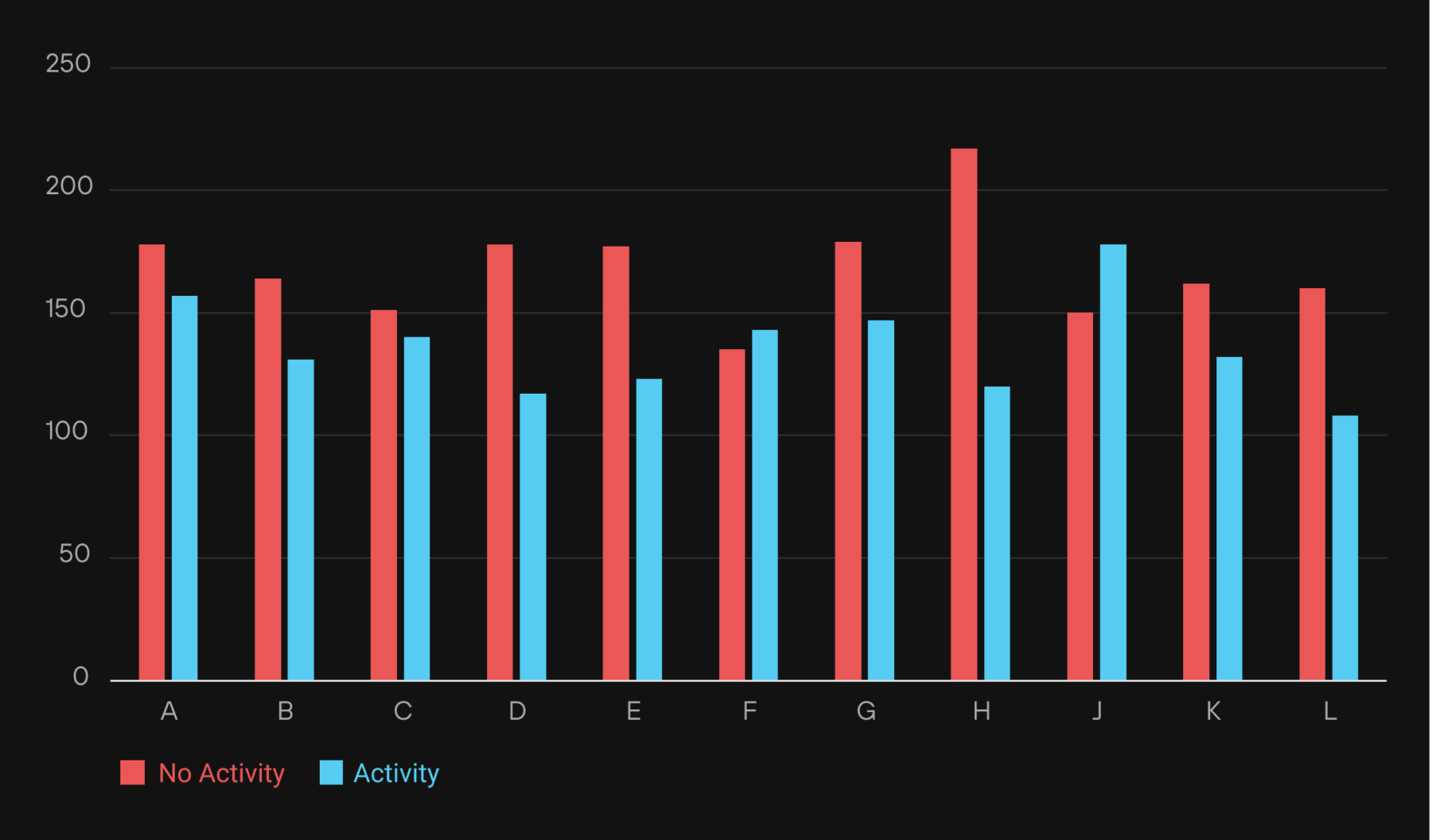

The Glucose Peak: This chart shows the difference in the blood sugar peak—how high a participant’s sugar rose with a walk (blue) versus without a walk (red).

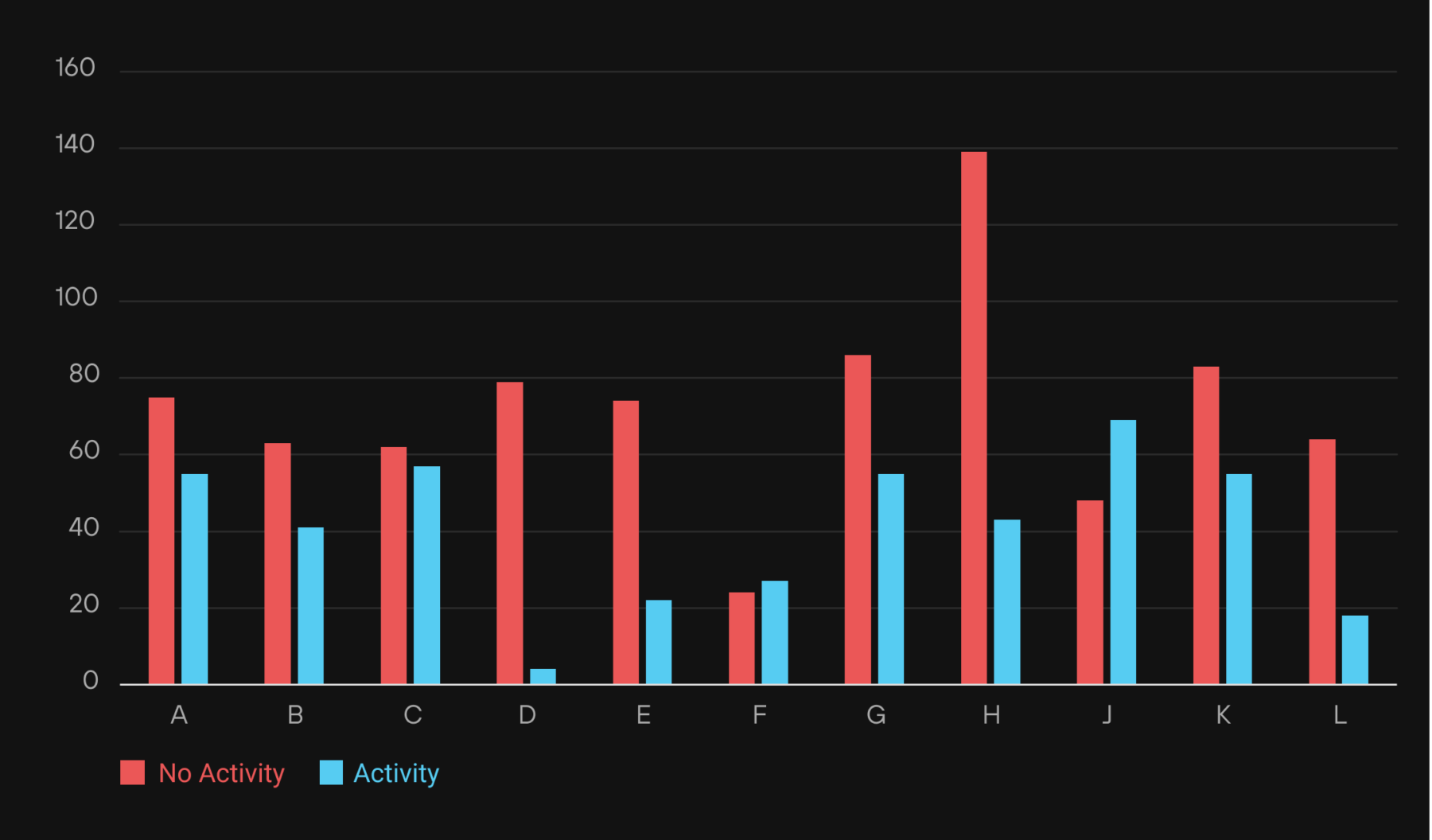

The Glucose Delta: This chart represents the change in blood sugar from the baseline when the participant drank the can of Coke to the highest peak, with a walk (blue) versus without (red). Lower is better.

The Science

These results comport with what we know about how our bodies use glucose, the primary fuel for our cells. Typically, when we consume carbohydrates (like sugars), our body converts those carbs to glucose, which enters our bloodstream. That triggers the release of insulin, which helps shuttle that glucose into cells to serve as energy or to storage, returning our blood glucose levels to homeostasis.

However, exercise can serve as an additional glucose disposal method. Our skeletal muscle tissue is a huge glucose sink. When we are moving, muscle contraction can enable our muscles to take up glucose from the bloodstream without a corresponding rise in insulin.

We also know that you don’t have to exercise profusely to realize these benefits. Research shows that moderate activity for just 30 minutes, three times per week, can improve insulin resistance and glycemic control. Another study found that many short bouts of movement throughout the day can be more beneficial than one long workout.

The Takeaway

To improve metabolic fitness, time bouts of even moderate exercise strategically throughout the day to blunt post-meal blood-sugar surges.

UPDATE:

In July 2020, we repeated the Coke experiment with members of the Levels community. In all, 37 members completed at least one arm of the challenge (most completed both). The results were similar to those of the internal experiment:

- ⬇️ Average glucose spike was 28% lower with a walk (+56.2 mg/dL vs. +40.4 mg/dL)

- ⬇️ Average glucose peak was 10% lower with a walk (145 mg/dL vs. 131 mg/dL)

- ⬇️ Average time out of range was 21% lower with a walk (56 minutes vs. 45 minutes)

Read More

- More evidence that exercise—even at low intensity—is great for metabolic health

- Optimize your exercise performance by tracking glucose

The Experiment

The Experiment