Dr. Ed Wu is the co-founder of Recora Health. This health-tech company helps guide people after a cardiac event like a heart attack or a chronic heart condition diagnosis like congestive heart failure. We talked to him about the impact of metabolic health on cardiac prevention and recovery, what diagnostics he looks for, and his favorite research papers.

Q: You’re an Internist by training and an entrepreneur—what drew you to the cardiac recovery space?

I have family and friends with diabetes and cardiac disease, and some have suffered debilitating heart attacks. So for me, heart health hits home. More than half of my patients have cardiac conditions, but there is never enough time to help them with lifestyle and habit change. And when referred to a cardiologist, my patients would similarly mention how stretched on time these specialists were. The focus on cardiac recovery and lifestyle factors has never really solidified in health care.

I have family and friends with diabetes and cardiac disease, and some have suffered debilitating heart attacks. So for me, heart health hits home. More than half of my patients have cardiac conditions, but there is never enough time to help them with lifestyle and habit change. And when referred to a cardiologist, my patients would similarly mention how stretched on time these specialists were. The focus on cardiac recovery and lifestyle factors has never really solidified in health care.

Cardiac rehabilitation facilities do a great job, but most are near hospitals, require 36 trips to a facility, and are subject to capacity constraints. As a Chief Medical Officer at a health system, I oversaw a sizeable cardiac rehabilitation program and realized some of these limitations. There is a huge need to offer something more convenient, contactless, and customized to patients in their home environments. For example, at Recora, we coach patients over live video sessions to exercise in their own chairs and living rooms. As a result, they quickly establish home exercise habits in their day-to-day lives.

We’re working with health systems that similarly realize pairing home-based cardiac recovery with a physician’s medication guidance can improve outcomes and slow the progress of cardiovascular disease.

Q: The data is evident on the importance of exercise and diet to cardiac recovery. What does a company like yours add to the standard of care?

Let’s say we’re talking about a person with diabetes who has their first heart attack, and they didn’t know they had heart disease prior. They get hospitalized. That may be their first introduction to meeting a cardiologist. That cardiologist is typically very busy. Providing diet and exercise advice at that moment is just not part of their routine. And if you have a good primary care physician (PCP), that cardiologist may just hand you off to them, but they may have less awareness of the importance of lifestyle in cardiac recovery.

But nowhere in here is there a focus on diet, exercise, or even optimizing LDL levels. You’d hope that conversation would happen either at a cardiologist’s office or a PCP’s office, but frankly—and this is from interviewing hundreds of cardiologists and PCPs—they don’t focus on these things. Why? Because it’s easier to write medication prescriptions and order diagnostic tests and basic labs.

At Recora, we move that recovery work into the home with dedicated specialists. This includes monitored exercise with exercise physiologists. We have health coaches that care about tobacco cessation and stress levels. We have dieticians who talk about, “Okay, why shouldn’t you be having those pancakes? Why shouldn’t you have that orange juice? Check out the label; look at the carbohydrate load.”

At least 20-30% of our clients have diabetes. Exercise and diet, especially watching glucose levels, are just as important as their LDL numbers and meds.

Q: You mentioned diabetes. What do we know about how metabolic impairment—insulin resistance, obesity, diabetes—increases the risk of cardiovascular disease?

There’s a lot of solid evidence at this point between metabolic dysfunction and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

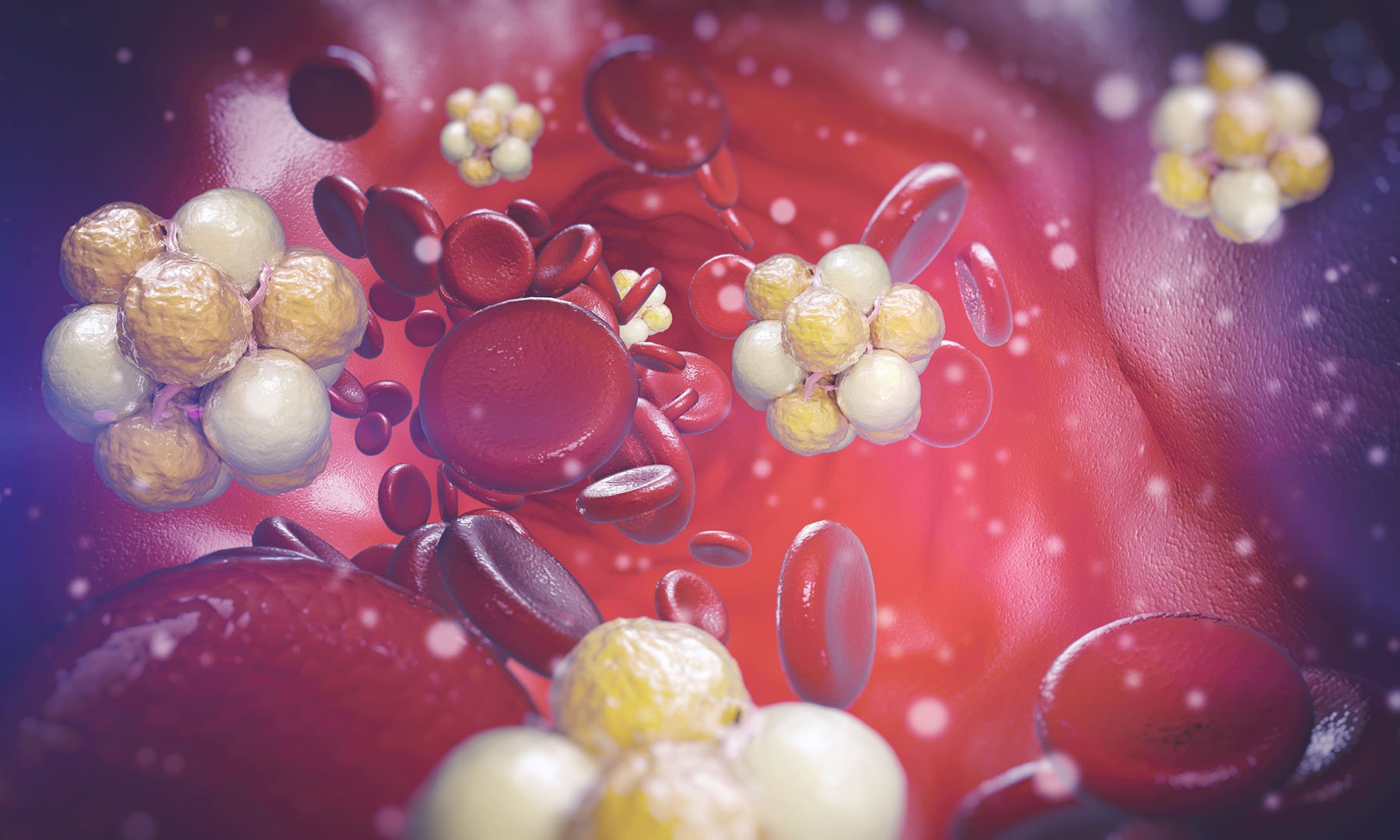

- First, several mechanisms link the two, including increased oxidative stress, increased blood clotting, and endothelial (blood vessel) dysfunction. Whether insulin resistance causes CVD directly is debated, but certainly, the obesity that can happen downstream of insulin resistance plays a significant role.

- The evidence is so strong that the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend people with diabetes aged 40-75 start statin therapy (which helps to address the above mechanisms) regardless of the CVD risk profile.

- More recently, we’ve seen that diabetes and obesity work in concert to increase the risk of CVD and even the eventual development of congestive heart failure (CHF) in healthy young adults.

- People with Type 2 diabetes have a 2 to 4-fold increase in the risk of incident CVD, ischemic stroke, and a 1.5- to 3.6-fold increase in mortality.

- For each 1% increase in A1c, the risk of future heart failure in adults is 8-32% higher! That means that as average glucose goes up, heart failure risk goes up significantly.

Q: What kind of preventative effect can reversing metabolic syndrome have on CVD?

- Starting late 2017, the AHA formalized primary prevention strategies under the umbrella of “Life’s Simple 7”—habits strongly associated with decreased risk of cardiac events. The seven are stopping smoking, losing weight, increasing physical activity, improving diet, lowering cholesterol, managing blood pressure, and reducing blood glucose.

- Studies consistently show that low-carb, unprocessed, nutrient-rich diets like a Mediterranean diet supplemented with either extra-virgin olive oil or nuts are associated with around a 30% reduction in heart attack, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality.

- Weight loss of 5% to 10% of initial weight, achieved through lifestyle intervention, can improve blood pressure, delay the onset of diabetes, improve glycemic control in people with diabetes, and improve lipid profile. All of this leads to a greater than 30% risk reduction of CVD.

Q: How should people at risk of cardiovascular disease or recovering from a cardiac event be thinking about metabolic health?

Much like those who have diabetes or are at risk of diabetes, people need to think of “time in range” for their glucose levels, meaning the time their blood sugar is within optimal ranges, aiming for more than 75% of the time.

Those who are recovering from a cardiac event similarly need to keep their metabolic levels in range. This can extend beyond glucose to lipid levels, triglyceride levels, and, of course, their physiologic levels like blood pressure and heart rate.

Another considerable factor: Regular aerobic exercise as part of a recovery program after a cardiac event is associated with a 20%-25% decrease in mortality in patients with CVD.

Q: What labs should people be looking at to see CVD coming?

On the ACC’s CVD Risk Estimator, three labs are drivers of the risk score: Total cholesterol (TC), LDL, and HDL (alongside risk factors like diabetes, hypertension, smoking, etc.).

That said, other laboratory tests can impact your risk of CVD:

- Cholesterol levels: In addition to total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL, the size of the particles that make up your LDL is important. Small-density LDL—lipoprotein(a)—is more likely to drive CVD. And if you have a lipoprotein(a) level that is 50 mg/dL or higher, there is clear evidence of higher CVD rates.

- Triglycerides (TG): Studies have found that TG can predict diabetes and are tied to higher mortality in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Triglyceride levels above 150 mg/dL are considered high and should be monitored or treated.

- Creatinine: This is a marker of kidney function. Reduced kidney function can signify CVD and can show up as elevated creatinine levels, with increased risk at 117 mmol/L or higher.

- Inflammatory markers: There is evidence tying elevated levels of homocysteine-c, CRP, and ESR to CVD (though these markers are non-specific and may indicate other conditions).

- Glucose: Aim to keep A1c below 5.7%, and use continuous glucose monitoring if you can.

- Obesity/adiposity: We start to see CVD incidence increase with BMI of 25 and up and much higher CVD incidence among those with BMI over 30.

Q: Any other papers you like on these connections?

- This paper is a fantastic, pathbreaking article recently published in The Lancet that can help us tailor our risk models and patient counseling on risk optimization based on ethnicity. It showed us that the traditional BMI risk categories we have been working with for years might be of limited use. They conclude: “revisions of ethnicity-specific BMI cutoffs are needed to ensure that minority ethnic populations are provided with appropriate clinical surveillance to optimize the prevention, early diagnosis, and timely management of Type 2 diabetes.”

- This article has a very nice table highlighting specific biomarkers (e.g., BNP, highly sensitive troponin, galectin-3, midregional proadrenomedullin, cystatin-C, interleukin-6, procalcitonin) that have a very high predictive value for incident and worsening heart failure. If someone tracked these closely, I am almost certain heart failure outcomes would drastically improve.